Pearl Harbor

80th Anniversary

80 years ago today the Empire of Japan launched a surprise attack on the United States of America. Just after dawn on 7 December 1941 Japanese planes launched from aircraft carriers struck the island of Oahu, Hawaii. Their primary target was the US Navy’s Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor.

In less than two hours they wrought havoc. As the Japanese pilots winged their way back to their carriers, behind them the harbour was ablaze and thick palls of smoke rose from numerous stricken ships. Chaos reigned as survivors worked frantically to save those trapped inside ships, or to help the wounded. Shock and disbelief soon gave way to anger and resolve to strike back. With this audacious attack, both nations now entered the Second World War, making it a truly global conflict.

The Path to War

US-Japanese relations had been strained throughout the 1930s over a variety of issues. Rivalry over influence and dominance in the Pacific had intensified as Japan invaded Manchuria in 1931, then the heartland of China in 1937. During the latter, attacks on American ships, citizens and businesses in China only worsened relations. By the end of the decade as war erupted in Europe, Japan increasingly sought to expand its dominance over other parts of Asia, rich in resources needed for the empire’s continuing war effort. The United States sought to block Japan’s moves, resorting to embargoes on military equipment and resources.

In mid-1940 the US Pacific Fleet was moved from San Diego to Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, and the Americans also began strengthening their bases further afield in the Pacific. These moves, intended to deter Japan from further expansion, had no effect. Despite continuous negotiations, in September 1940 Japan invaded Tonkin (northern Indochina). When they continued their advance by invading southern Indochina in July 1941 the United States stopped exporting oil to Japan. This was a key moment on the road to war. Now faced with its main oil supply being cut off, Japan’s solution was to launch a military operation to capture the rest of mainland and maritime Southeast Asia, rich in resource, including oil. The Japanese would not tolerate the Americans thwarting their plans to dominate the region.

Warnings

As their planned ‘Southern Operation’ would involve the capture of British territories, Japan felt certain that the United States would intervene militarily. Therefore, they included the capture of US territories in the Western Pacific, such as the Philippines, Guam and Wake Island in their plans. The attack on Pearl Harbor was designed to so damage the US Pacific Fleet that it would be out of action for at least six months – time enough for Japan to complete its conquests without the Americans interfering.

There were warnings of the Japanese decision to go to war with the United States and the impending attack on Pearl Harbor. However, for a variety of reasons they were not heeded and as a consequence the Americans were taken completely by surprise.

US cryptanalysts had broken Japanese diplomatic codes well before the Second World War, including the latest version, ‘Purple’. In addition, as tensions mounted, they were monitoring communications between Tokyo and Japanese agents in Hawaii. In September 1941 they intercepted a request from Tokyo for detailed information about US Navy dispositions in Pearl Harbor. These intercepts provided some insights into possible Japanese intentions, but they were still unclear.

Further diplomatic intercepts indicated Japan was preparing for an aggressive move into Southeast Asia. One was the instruction to Japanese embassies and consulates to prepare to receive information through coded radio broadcasts - known as the ‘Winds Code’, while a subsequent message ordered them to destroy their code material and code machines. The latter led authorities in Washington DC to issue a direct ‘war warning’ message to Pearl Harbor on 27 November. Further warnings were issued over the next several days.

Then on 6 December, US codebreakers began intercepting a lengthy fourteen-part message from Tokyo to their ambassador in Washington DC. By midnight it had been decoded, but a clumsy, convoluted and inefficient distribution of this intelligence proved fateful. The ambassador was to inform his US counterpart of the contents at 1.00 pm on 7 December - just before the attack on Pearl Harbor was scheduled, but too late to prepare for it.

The result was a farce. The Americans had the full message before the Japanese ambassador, but failed to act upon it in a timely manner. While they did alert Pearl Harbor via telegram on the morning of the 7th, once again failures in recognising the importance and simple delays in distribution meant the warnings did not reach the key people on the ground in time. The Japanese ambassador, facing his own delays in decoding and typing up the message didn’t deliver it to the US Secretary of State until 2.20 pm - one hour after the attack had begun.

Another key factor in why so many warnings went unheeded was that most American decision-makers and leaders did not interpret these Japanese diplomatic messages as a conclusive intent to go to war. This is understandable in part, as the fourteen-part message only said that Japan had come to the conclusion that an agreement could not be reached with the United States “through further negotiations.” So, although it vaguely pointed to a break-off in diplomatic relations, it did not confirm such a break, and it certainly contained no explicit declaration of war.

The Attack

With diplomatic negotiations to avert war still underway, on 26 November the First Air Fleet under the command of Vice-Admiral Chūichi Nagumo departed Japanese waters. The main strike force was six fleet aircraft carriers escorted by a host of other surface vessels and submarines. Taking a more remote northerly route and screened by weather fronts, they approached Hawaii undetected from the north. At 6.15 a.m. on 7 December the first of 353 Japanese aircraft began taking off from the carriers, 320 kilometres north of Oahu. Meanwhile five Japanese midget submarines approached Pearl Harbor but they were soon detected with the destroyer USS Ward firing the first shots near the harbour entrance. Four were hunted down and sunk, while the fifth grounded, offering up Japan’s first prisoner of war. The submarines had minimal effect on proceedings.

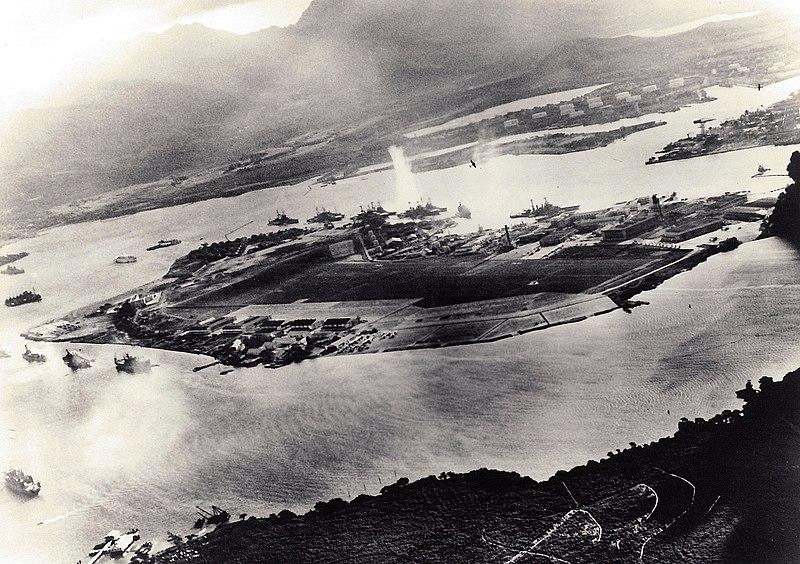

On Oahu, soldiers, sailors and civilians woke and began to go about their business or leisure that Sunday morning. Then, at 7.48 a.m. the attacks began. First they hit aircraft on the ground at various locations on the island before the main attack on Pearl Harbor began at 7.55 a.m. Commander Mitsuo Fuchida exclaimed “Tora! Tora! Tora!” – the code words that they had caught the Pacific Fleet unawares. Their primary targets were the major ships – aircraft carriers and battleships. The other priority was to destroy the American air force on the ground so they could not interfere.

After many on the ground initially thought their own aircraft were rudely conducting practice runs on a Sunday morning, the reality quickly became apparent. Japanese torpedo bombers swooped in low over the harbour, their weapons specially designed to run in shallow waters such as Pearl Harbor. Many torpedoes found their mark against the big warships moored at Ford Island in the harbour’s centre. High-level and dive bombers also scored hits against a variety of ships and particularly against the airfields, catching the American aircraft on the tarmac. A few did get airborne but to little effect against such overwhelming odds. Things were going very well for the Japanese.

After a brief lull as the first wave headed back to the carriers, a second wave struck just before 9.00 a.m. With visibility reduced by the smoke and what defences could be organised now fully alert, this second wave was less successful. Nevertheless they did inflict further damage before they too sped away northwards. As they landed the exhilarated aircrew celebrated their apparently devastating victory. Any thoughts of launching a third wave were not practical as the aircraft would not have time to refuel, refit, and carry out another attack and return to the carriers before dark.

Casualties and Losses

A total of 2,403 Americans were killed at Oahu that day including 68 civilians, while 1,178 lay wounded. 21 US Navy vessels were damaged or sunk, including all eight battleships, one ex-battleship, three cruisers, seven smaller vessels and a floating dry dock. Yet all but three were later salvaged and most returned to active service. American air power on Hawaii was almost entirely wiped out that morning, with a total of 188 U.S. aircraft destroyed and 159 damaged - almost all on the tarmac.

The Japanese suffered just 64 killed, along with 29 aircraft and 5 midget submarines lost. However, the main prize along with the American battleships was to have included the three US aircraft carriers normally stationed at Pearl Harbor. But as fate would have it, none were there that morning. It was an important piece of luck for the Americans, even amid the carnage that had taken place at Pearl.

Who was to blame?

The US government made nine official inquiries into the attack between 1941 and 1946, and a tenth in 1995. In addition, a plethora of books have been produced on the topic. Many culprits have been identified, most of which point to failures of senior US leaders and military commanders, mainly the commander of the US Pacific Fleet, Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, and Hawaii’s Army commander, Lieutenant General Walter C. Short. These shortcomings include:

- Failure to interpret Japanese intentions through codebreaking of diplomatic messages. While these were somewhat ambiguous and not one hundred percent conclusive, more should have been apparent. Poor interpretation, interservice rivalry and inefficient distribution contributed to the failure.

While the Americans could read Japanese diplomatic messages, what was really needed was the same capability with Japanese naval codes. Work had been underway for some years on this problem, but by December 1941 the Imperial Japanese Navy’s JN-25 code was only in the very early stages of being broken, and certainly far from being readable. Success with JN-25 would come later, but far too late for Pearl Harbor.

- Failure to conduct long-range air reconnaissance of the most likely approaches to Hawaii. Washington had ordered this and assumed it was being done. Furthermore, Army assumed Navy was doing it. This pointed to a lack of Army-Navy liaison generally. Although lacking sufficient aircraft to carry out extensive searches, they nevertheless could have conducted adequate ones.

- Failure to have aircraft on Hawaii ready for action. They were mostly lined up, out in the open on their tarmacs, not ready to launch.

- Failure to have the island’s anti-aircraft defences adequately ready to meet an attack.

- Failure to utilise the island’s full radar capability. Even with minimal installations operating on the morning of the attack, they still managed to detect the Japanese first wave around 40 minutes before they arrived - in time to provide at least some warning. Unfortunately the report from the radar operators was dismissed as likely being a flight of friendly aircraft coming in from the mainland. “Don’t worry about it,” they were told.

As has been persuasively argued over the years, much of the above failures were ultimately down to Kimmel and Short, in that they were not sufficiently vigilant. The two men were in command of the United States’ key outpost and the key force on the frontier of their nation’s Pacific defences. And since outposts exist so those in the homeland can sleep easy (or at least not be taken unawares), they are supposed to maintain a high level of vigilance against surprise attacks. Kimmel and Short bear the main responsibility for that lack of vigilance through their lack of imagination that such an attack could happen and their assumption that it would not happen.

More broadly the Americans underestimated the Japanese Navy’s capability to pull off an attack of such scale and precision. Better military intelligence should have indicated their true capabilities. As most everyone thought war between the two nations was likely, they should have been focussing on Japanese military technology, tactics and capabilities.

They also failed to understand that Japan may not apply the same logic as the United States regarding the rationale of going to war. The Japanese were a different culture and their military mindset was especially so. Taking on a much larger, more powerful enemy with slim prospects of long-term success had not daunted the Japanese before.

As Steve Twomey put it in his 2016 Countdown to Pearl Harbor, ‘Assumption fathered defeat’.

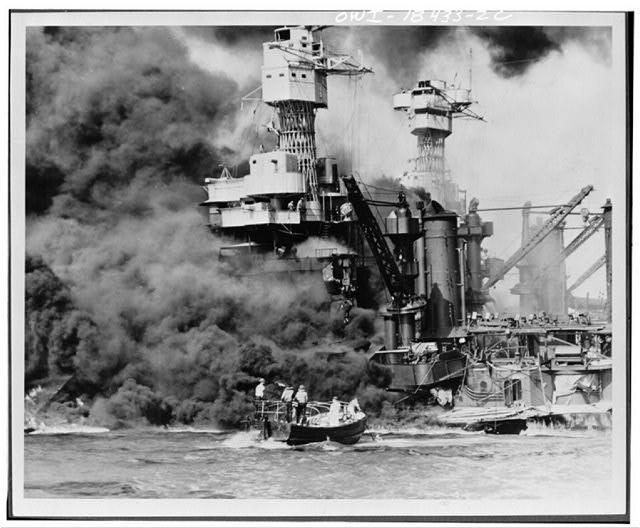

The battleship USS Arizona ablaze and sinking after being hit by four bombs. 1,173 men aboard the Arizona died (almost 80 percent of the crew), and by far the majority of all American lives lost on 7 December 1941. The wreck remains in place and is today a memorial to those who died. Source: US National Archives and Records Administration, NLR-PHOCO-A-8150(29).

A small boat rescues a USS West Virginia crew member from the water after the battleship was hit by multiple torpedoes and bombs. West Virginia was later raised and returned to fight at Surigao Strait, Leyte Gulf, Iwo Jima and Okinawa. Source: U.S. Navy, Office of Public Relations. Library of Congress, fsa 8e00810

Conspiracy Theories

Over the years, conspiracy theories about Pearl Harbor have been put forward, arguably on par with those surrounding the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963 and the 9/11 terrorist attacks in the United States in 2001. These mainly point to theories of advanced knowledge about the attack; specifically that either British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and/or US President Franklin D. Roosevelt deliberately withheld knowledge of the impending attack to ensure America’s entry into the war, with Japan the seemingly unprovoked aggressor. While plausible to some, such theories have never stood up to scrutiny.

Consequences

In the early afternoon of 8 December, President Franklin D. Roosevelt addressed a joint session of Congress.

“Yesterday, December 7, 1941 — a date which will live in infamy — the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan”.

The speech went on to emphasise that the two nations had been negotiating to resolve their differences and to maintain peace, thus the attack without warning or a declaration of war was duplicitous and deceitful. This act of ‘infamy’ indeed struck a chord with Americans; their anger at the losses inflicted by this underhand attack galvanised the country with resolve to avenge their dead and defeat Japan was undeniably infused with a clear sense of moral ascendancy.

While there is no evidence that in the wake of Pearl Harbor Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto either said or wrote of his fears that the attack had only awakened ‘a sleeping giant’ (as portrayed in the movies), it does seem clear that he was pessimistic about Japan’s ability to win a protracted war with the United States.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor had aimed to put the US Pacific Fleet out of action for six months. Ironically, almost exactly six months later, to the day, the Americans struck a crushing blow against the Imperial Japanese Navy at Midway in the Central Pacific. But unlike Pearl Harbor, at Midway the aircraft carriers were not missed. With four Japanese fleet carriers sunk, it was a turning point in war between the two nations. After Midway came Japan’s inexorable retreat from all it had gained – all the way back to their Home Islands and ultimate defeat in August 1945.

Significance for Australia

The attack at Pearl Harbor was actually preceded by the near simultaneous Japanese invasion of Malaya, some 50 minutes prior. Within hours further attacks took place upon US forces in the Philippines, Guam, and Wake Island, and on the British in Singapore and Hong Kong. While the attack on Malaya, which brought Australian airmen and troops into action, was more threatening as far as Australia was concerned, the magnitude and repercussions of the stunning blow the Japanese pulled off at Pearl Harbor was greater. At last the Americans were in the war, but so too was Japan. Soon Australia would be under threat as the Japanese advanced southwards, seemingly unstoppable. But they were stopped through a combined Allied effort in the Pacific and Asia as the tide was turned at places like the Coral Sea, Midway, Guadalcanal, Milne Bay and Kokoda. The industrial might of the United States would prove decisive in securing an Allied victory in the Second World War. For the Americans it had all begun at Pearl Harbor that fateful Sunday morning.

Further Reading

Day of Infamy / Walter Lord (1957)

At Dawn We Slept: The Untold Story of Pearl Harbor / Gordon W. Prange with Donald M. Goldstein and Katherine V. Dillon (1981)

Pearl Harbor: The Verdict of History / Gordon W. Prange with Donald M. Goldstein and Katherine V. Dillon (1986)

December 7, 1941: The Day the Japanese Attacked Pearl Harbor / Gordon W. Prange with Donald M. Goldstein and Katherine V. Dillon (1988)

Pearl Harbor: Final Judgement: The Shocking True Story of the Military Intelligence Failure at Pearl Harbor and the Fourteen Men Responsible for the Disaster / Henry C. Clausen and Bruce Lee (1992)

Pearl Harbor 1941: The Day of Infamy / Carl Smith (2001)

Countdown To Pearl Harbor: The Twelve Days To The Attack / Steve Twomey (2016)