'The army was all I knew'

Warning: the following story discusses post-traumatic stress disorder.

If you or someone you know needs help, support is available at Lifeline on 13 11 14 or Beyond Blue on 1300 22 4636. If you are an Australian veteran or family of a veteran, you can also call Open Arms Veterans & Veterans Families Counselling Service on 1800 011 046.

The Australian War Memorial has worked with veterans and their advocates to commission a work of art to recognise and commemorate the suffering caused by war and military service. The art work represents those affected by operations and during training; in war and on peacetime service.

Learn more.

Pennie Looker pictured in her Army uniform. Photo: Courtesy Pennie Looker

Pennie Looker knows all too well about the sufferings of war.

As a sergeant in the Australian Army Psychology Corps, she was acutely aware of the impact of service and how it affected people.

And then she had a stroke.

“My role was stressful; I make no bones about that,” she said.

“I was struggling to cope, and I didn’t want to admit it.”

A psychological examiner, she tried for years to hide her own mental health issues while continuing to help others.

“The hard part was hearing everyone else’s stories, but knowing I had my own as well,” she said.

“When you hear these stories over and over again, and when you know someone who then suicides, it can be really hard to deal with.

“Being in the Psych Corps … it was hard to put my hand up and say I needed help to begin with, but then I had the stroke.

“I thought I’d been doing well, but some of the things you see, you never forget …

“I reached the point where I too could no longer cope.

“I was a sergeant, acting as a warrant officer, so I had to look after the welfare of all the staff, and they weren’t coping either.

“I was trying to look after them, and I was pushing my own things to the side – pushing down and pushing down and pushing down – and it all came to a head in 2014.

“I had a stroke, and that was kind of the end of it all for me.”

Pennie in the stroke ward after having her stroke. She describes it as: 'Possibly the scariest and most lonely time of my life.' Photo: Courtesy Pennie Looker

A mother of three, Pennie had been to see the doctor the week before because she kept getting headaches that wouldn’t go away. She had been trying to ignore the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and had kept herself so busy that she “didn’t have the time to stop and think”.

“It was all related to the stress, and I was on leave for a couple of weeks to try and reset and settle myself,” she said.

“I was on the phone to my husband, and he couldn’t understand what I was saying.

“I kept trying to speak to him, but the words were all jumbled and not right, so he broke a few laws and raced home.

“They couldn’t get an ambulance because there were no ambulances free, so he got the kids to the neighbours, and rushed me to the hospital.

“I was 34 … and I was admitted to the acute stroke ward.

“It was scary. It was horrible. And it was really difficult.

“It took me two and a half years of rehab to get my speech back properly and to really work on moving my body properly again.

“It was the hardest time in my life … but if my husband hadn’t got there in time, things could have been a lot worse.”

Pennie recovering from one of the 38 surgeries she had to have as a result of her injuries. She is pictured doing her first walk without the aid of another person, but still with the help of a walking frame. Photo: Courtesy Pennie Looker

She was medically discharged from the army in 2015, after 19 years of service, and was eventually diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder.

“It was hard – very hard,” she said.

“The discharge process was, and is, distressing. It is lonely. It is isolating. And it is so incredibly challenging.

“You don’t know who you are anymore when you’re not there. You’ve got to reinvent yourself, and that’s really hard to do.

“The army was all I knew. And I didn’t know anything different.

“I’d joined at 17 and all my friends and all my family were army.

“My grandfather was in the British army as a cook, and then my brother joined when he was 17. He told me I wouldn’t be able to hack it, that it would be too hard for me, so I did it; I joined, and I absolutely loved it.”

Pennie in the Army. "My brother ... told me I wouldn’t be able to hack it, that it would be too hard for me, so I did it; I joined, and I absolutely loved it.” Photo: Courtesy Pennie Looker

She began her career in the army as a cook, like her grandfather, and went on to serve as a clerk before completing her psychology degree and becoming a psychological examiner.

As a psychological examiner in the army, Pennie was involved in critical incident responses, suicide interventions and risk assessments, as well as the screening processes for troops when they were deployed, both in country and when they came home.

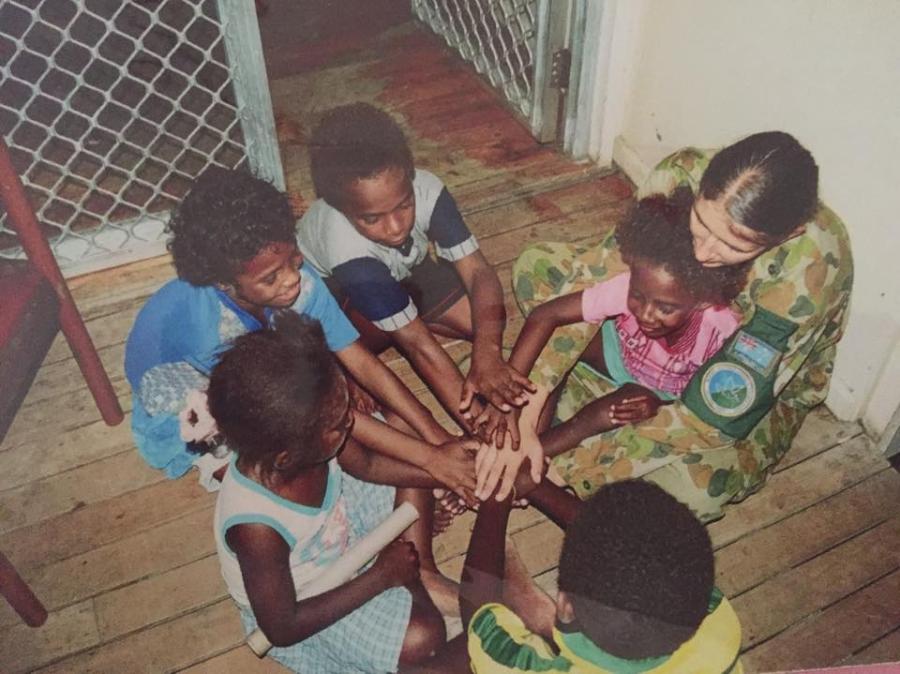

She deployed three times; once to Solomon Islands as a clerk, and twice to East Timor. Her husband, another army veteran, also deployed multiple times, serving in Iraq and Afghanistan.

“I met my husband in the army and he deployed, I think it’s 12 times – I don’t know, we lose count. So we were kind of high fiving each other as we went on courses or out bush or on deployments, and were working out the best way we could cope with everything that we had going on with work and all the requirements there and raising kids.”

Pennie deployed three times; once to Solomon Islands as a clerk, and twice to East Timor. Photo: Courtesy Pennie Looker

Life was busy, but Pennie loved her work as a psychological examiner.

“It’s so rewarding,” Pennie said.

“And I loved it. To be able to be there for somebody in their time of need and make sure they get the support they need, or the support they want, is so rewarding, but it’s not just about helping people when they are struggling.

“It’s also about giving them the education to help them get through things in the future or help them with a change in career.

“There are just so many different aspects to the job as a psych examiner.

“There was so much good to it – so much good – and I absolutely loved my time in the army.”

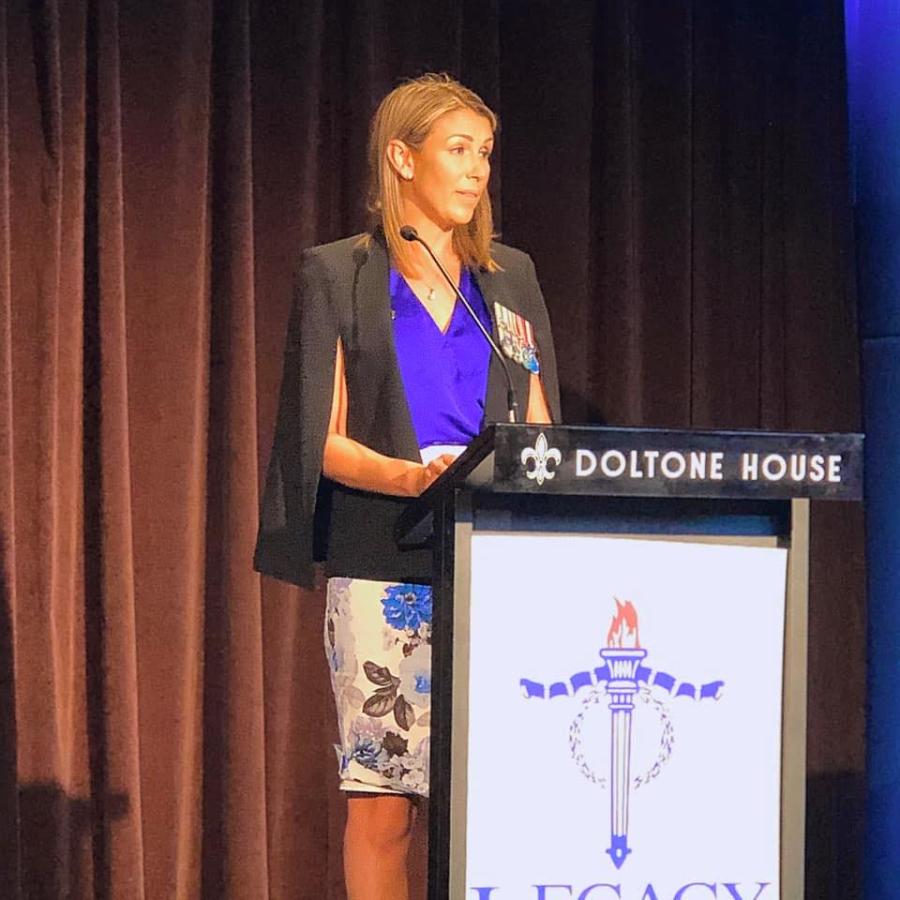

Pennie loved her work as a psychological examiner in the Army. Photo: Courtesy Pennie Looker

She trekked the Kokoda Trail in 2016 to help raise awareness of veterans’ issues, and she has made it her mission to help others who are struggling with PTSD.

“I still struggle from day to day,” she said.

“And I still have night terrors, and waves of depression and anxiety.

“The army was all I knew. I didn’t know any different. And it was really difficult to find a doctor, or a psychiatrist, or a psychologist, who understood trauma, or anything to do with the military.

“Even just finding friends that I could relate to, or who could relate to me, was really hard.

“As a psych examiner, you’re one of the other ranks too, so they are your cohort, your mates, and you deploy with them, you train with them, you do everything with them.”

Pennie is a passionate advocate for veterans and their families. Photo: Courtesy Pennie Looker

Pennie is one of the people who have been working tirelessly with the Australian War Memorial to advocate for a Sufferings of War and Service sculpture to recognise and commemorate the suffering caused by war and military service.

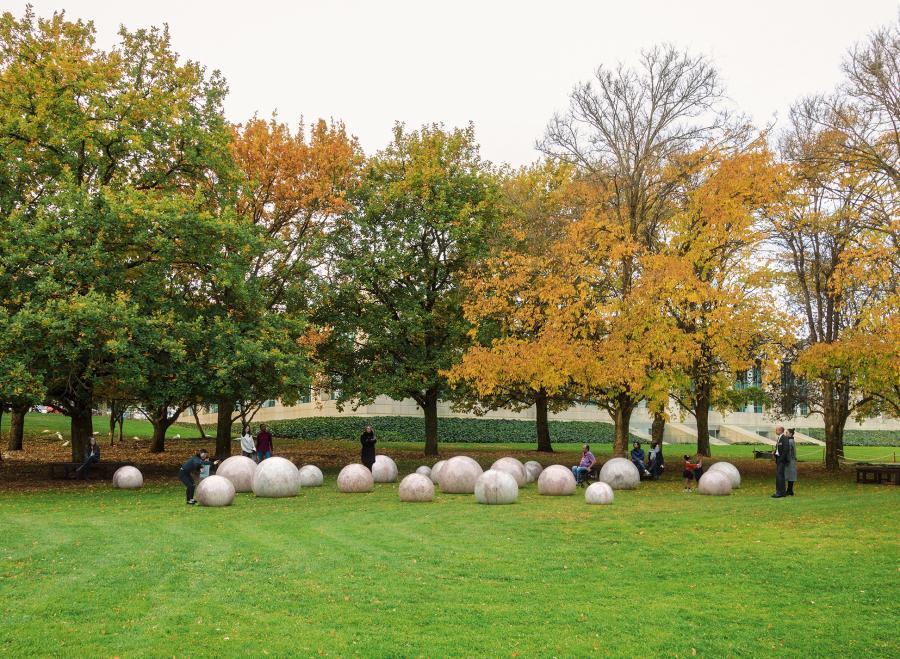

Pennie was part of a committee that helped secure funding and provide the Memorial with feedback and insights that led to the selection and commission of a work by artist Alex Seton, For Every Drop Shed in Anguish.

It will take the artist two years to create the work, which will be installed in the Memorial’s Sculpture Garden in 2023.

Pennie said she hoped the sculptural installation, a field of sculpted Australian pearl marble droplets, representing the blood, sweat and tears that have been shed in anguish, would provide a point of connection for all those who had suffered as a consequence of service.

“There’s so much that people don’t see,” she said.

“They just see the mask that we all put on to pretend we’re okay.

“But you’re dealing with everything you’ve lived through – everything you’ve seen, everything you’ve heard – and your family is dealing with it all as well.

“To have something that represents how hard it is for veterans and their families is so important.

“We lose so many, but there’s so many of us still here, who are suffering, and just trying every day to get through, with our families there alongside us, helping.

An artist's impression of what the Sufferings of War and Service sculpture, For Every Drop Shed in Anguish, will look like when it is installed at the Australian War Memorial.

“This sculpture is about making it right there and visible for everyone to see, because it hurts, and it hurts in a way that isn’t visible; it hurts in a way that is pure anguish and suffering.

“And it’s difficult, not just for those of us who have been through it, but for the families who are here with us, trying the best they can to get through the hard days, and really applaud the good days.

“I’m very lucky. I have the most amazing, supportive family, but there are so many veterans out there who don’t have a partner to support them and understand them, or someone who can be there for them, and they’re the ones we are losing ... because it’s so damn hard to be with someone who loses their mind over a milk ring on the bench.

“Your temper gets so short, and anxiety can come out in strange ways. I can burst in to tears for absolutely no reason, just because my anxiety is peaking, or start shaking.

“And my story is not singular, it happens to so many people, and that’s why we are losing them, because they feel they have nowhere to turn.

“They might not have family, or anyone around them. And it’s lonely enough, even with that support around you, but when you don’t have it, you’re just left with what goes on in your head. And it’s not nice.

“There’s the injuries you can’t see. There’s the illnesses you can’t see. And it’s hard when we come home.

“This sculpture is about recognising that it’s hard, and that not all of us come home intact in ways that you can see.

“It not only affects us, but there’s the ripple effect on our families and our friends and everyone around us.

Pennie with her family in Sydney. Photo: Courtesy Pennie Looker

“It’s important these stories are told because if they are not told, then people don’t understand what we go through.

“They don’t understand why sometimes someone ringing will cause a panic attack and we don’t answer the phone.

“They don’t understand why we can’t go into a busy shopping centre, or why it might take us half an hour in the car, egging ourselves on to actually go into the grocery store, because of the crowds and the loud noises.

“All those things can affect us in different ways, and I say us as a collective because everyone experiences it differently, and has their own triggers.

“There are just so many things the general population can’t understand unless we start talking about it and making it general conversation.

“When we come home, we’re not always whole, and you may not always see it, but we feel it, our families feel it, and it needs to be talked about, and it needs to be recognised.

“I love the plan for the sculpture because it’s not neat and tidy. It’s spread out, and it’s big, and it can’t be missed. It’s something that is really going to make people ask questions and perhaps give a space for people to sit and talk, a place to sit and reflect.

“The fact it’s a natural stone and it’s going to be out in the elements, means it’s going to change over time, just like we all do.

“Alex’s vision opens the horizon to hope and new promise. The Australian veteran community and their families need to know and feel this hope and new promise.

“It’s about recognising the heartache, and the pain, and the anguish, and it will go a long way to helping people understand.

“Honestly, I’d give anything to still be in the army. “It’s who I’ve always been, and I’d go back in a heartbeat if I could.”

The Australian War Memorial has commissioned a work of art to recognise and commemorate the suffering caused by war and military service. The sculptural installation, For Every Drop Shed in Anguish, by artist Alex Seton, will provide a place in the Memorial’s Sculpture Garden for visitors to grieve, to reflect on service experiences, and to remember the long-term cost of war and service. A field of sculpted Australian pearl marble droplets, it will be made by the artist over the next two years and installed in the Sculpture Garden in 2023. For more information about the Sufferings of War and Service sculpture, visit here.

Defence All-hours support line – The All-hours Support Line (ASL) is a confidential telephone service for ADF members and their families that is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week by calling 1800 628 036.

Open Arms – Veterans & Families Counselling Service provides free and confidential counselling and support for current and former ADF members and their families. They can be reached 24/7 on 1800 011 046 or visit the Open Arms website for more information.

DVA provides immediate help and treatment for any mental health condition, whether it relates to service or not. If you or someone you know is finding it hard to cope with life, call Open Arms on 1800 011 046 or DVA on 1800 555 254. Further information can be accessed on the DVA website.