HMAS Patricia Cam and the search for Percy Cameron

Percy Cameron’s life was commemorated in a Last Post Ceremony at the Australian War Memorial.

Seventy-six-year old Janice Braund has spent a lifetime searching for her father. He died just three weeks before her second birthday after the auxiliary transport ship HMAS Patricia Cam was bombed by the Japanese off the coast of northern Australia 75 years ago. Although officially listed as lost at sea, a chance encounter presented a different story, leading Braund on a quest to find out what really happened to her father.

“This is the culmination of an enormous trip that I have had since I was 18,” Braund said. “I don’t have to look any more, everything’s wonderful. I’ve got there, after all these years, 75 years, looking for him … or wondering about him from the time I was two, it’s absolutely first class, and I know he would be tickled pink.”

Percy Cameron’s life was commemorated in a Last Post Ceremony at the Australian War Memorial marking the 75th anniversary of the sinking of Patricia Cam on 22 January 1943. He was one of 19 crew members on board Patricia Cam carrying supplies to outlying missions when a Japanese floatplane, with its engine cut, dove out of the sun at about 1pm and released one of its bombs. Also on board were five local Yolgnu men and Reverend Leonard Kentish, the senior Methodist Missionary in the Northern Territory, who was in charge of the local coast watchers.

Janice Braund: “I don’t have to look any more, everything’s wonderful."

Back in Sydney, Cameron’s mother immediately knew that something was wrong. “His mother used to meet my mother down at Bronte Beach,” Braund said. “She came down to the beach one morning … and she said, ‘Nancy, Percy has gone, I’ve seen his cap floating on the water.’ When the navy finally notified mum that he had died, it was on that day.”

Cameron was 24 years old. His widow had just celebrated her 22nd birthday. Devastated by his loss, she refused to speak of him.

“My mother would never speak of my father for some unknown reasons. She found it impossible, I suppose,” Braund said. “I’ll never know what her feelings were or anything. It was just a closed subject. There was absolutely nothing … Maybe it was just that it was just so awful. Any inquiries that I made to her met with nothing. I used to bring his medals out and talk about those, or photographs of him, and they were quietly packed away before my eyes and that was the end of the subject.”

Over the years Braund pieced together tiny snippets of information to build a picture of her father.

“All I know is he wanted to join the navy when he was 16, he loved the bell bottom blues of the trousers, and he was a very keen sportsman … a great athlete,” she said.

“He represented New South Wales … in Aussie Rules and … boxed under the name of Dick Johnson at Rushcutters Bay, but under what weight I’ve got no idea. He used to bundle up his clothing in his bed, he must have been 17 or 18, and pretend that he was there, and he would climb out the back window and go down to Rushcutters Bay, and … box 10 rounds… and then climb back in again … and say that he slept the night …

“They were just like little pearls that dropped every now and then. Perhaps they were in the mood to say something, or just remembered something, but they all said what a great personality he was and they really enjoyed his company.”

Percy Cameron and his wife Nancy on their wedding day.

Braund was 18 when a chance meeting changed everything. She was studying occupational therapy and had enrolled in a woodwork course at Ultimo in Sydney.

“I was in the line … and the man said to me: ‘Are you Janice Lee Cameron? Well, I helped bury your father, and I called my daughter after you.’ [It was] the most extraordinary neck prickling situation that you could ever have: that somebody out there knew and had been associated with my father. So that was the first really lovely words that I’d ever heard about him. He spoke of him with great love and care and he said [my father] always had my photograph and my mother’s photograph alongside of wherever his belongings were on the ship.”

Although she lost contact with the man, his words never left her, and she became determined to find out where her father was buried.

“Oh good grief, it meant everything because it meant somebody out there actually had known him, been close to him,” Braund said. “It was a remarkable thing to happen … We haven’t been able to track him at all. All I know is that the words that he used were so enlightening and so emotional, that somebody out there knew him …

“So that was the beginning of an affair I had with the navy … I went to the navy and I said, ‘Well, where’s my father, he’s buried, he’s not lost at sea,’ so with an enormous amount of inquiries that lasted from the time I was 18 to the time I was 50 I drew a blank.”

It was then that she read an article about Patricia Cam and the Reverend Leonard Kentish, who was taken prisoner by the Japanese and endured severe beatings and torture before being beheaded at Dobo Island on 4 May 1943.

“I thought heavens above … so I wrote to the chap called John Leggoe, who had written a book, Trying to be sailors, and asked him did he know anything about my father. And he spoke very eloquently in a letter to tell me what a lovely man he was and all these other things and told me he had helped bury my father.

“When the boat was bombed twice, and they were in the water, they formed rafts, and whatever they could, and they swam for many hours … and the tides drifted them onto the Wessel Islands. When they woke up in the morning they dragged my father up the beach with another first Australian man [Milirrma Marika] who had been there on the boat… My father died at 8 o’clock in the morning and the other man died at 2 o’clock in the afternoon, and they buried them with rocks over the top of their graves so the crocodiles couldn’t dig them up.”

In the letter, Leggoe described her father’s bravery in the aftermath of the bombing. “He made a dash for the only gun in an effort to return fire, but the ship sank under him before he could get any shots away … I can assure you that your father was a man of whom you can be very proud.”

A group portrait of survivors of the HMAS Patricia Cam, which was sunk on 22 January 1943.

Leggoe was among the survivors who were rescued on 29 January and taken to Darwin. In all, four of the 19 sailors and three of the Yolgnu men died as a result of the sinking.

“That was further evidence, so I went back to the navy, and they said, ‘No, he’s still lost at sea,’ and I got very cranky after a little while and said, ‘Well look, you had a plane that came across, dropped supplies, and you had a boat that went to pick them up, you have the coordinates of this area, please go and bring my father’s remains back.’”

Then, in 2013, a group of heritage researchers known as the Past Masters found a piece of ship’s timber on the beach on the Wessel Islands. They had been looking for the site where ancient coins had been found in 1943, but Mike Hermes’ discovery of the ship’s knee led them to the Patricia Cam story and Percy Cameron’s daughter.

“We took it back to Gove and when I was going through the finds of the expedition I realised it was pretty close to where the Pat Cam went down,” said Mike Owen. “From that I just worked back and that led me to the Patricia Cam and the RAN website and … a picture of the survivors on the beach … I started looking at it more closely and … I saw what I thought was a grave with… a paddle as a grave marker. And that I believe is where Percy Cameron and Milirrma Marika are buried, and have been for 75 years.”

Owen knew of Braund’s attempts to locate her father’s grave and decided to find her.

“I didn’t want her to read about it in the paper, so I just went through the phonebook, and I found a place in Sydney with two Braunds at the same address,” he said. “I phoned one of them up and Judy Braund answered. She said, ‘No, no, I might be a distant relation, but probably not, but Jan lives just over the road and she’s been out shopping and she’s just come home – if you phone her now, you’ll get her.’ So I phoned her up and told her, ‘I know where your father is buried,’ and that’s how it happened.”

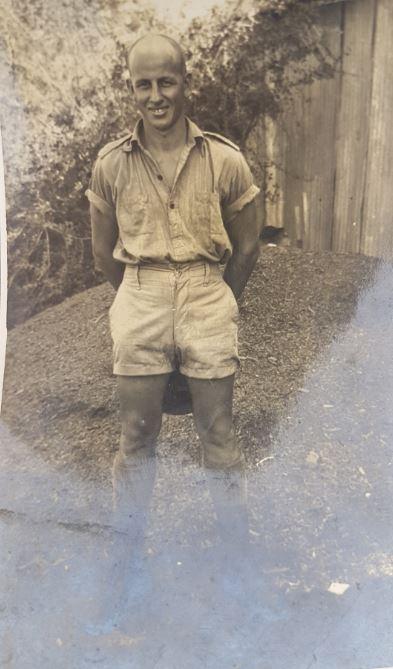

Percy Cameron, pictured third from left: "A man of whom you can be very proud."

For Braund, it was the piece of news that she had spent a lifetime waiting for.

“Every scrap of anything that was ever said to me, of deeds done or of places that he might have gone to, like gymnasiums or picnics in the car, they’ve all been wonderful parts of an incomplete … jigsaw puzzle,” Braund said.

“Over the years, about every five to six years, or maybe seven, someone in the world has got in contact with me and said I knew your father, and did this and that …

“Then through the years, because of all the little bits and pieces, I thought, this guy wants to be found. There’s no doubt about it in my mind that behind everything is Percy Cameron. He wants to be found, he wants me to know that he’s okay, and then I’m okay, and that’s a powerful thing to have.

“It’s just gathering anything that you can get of a person that has gone. My feelings have always been strong that if I could get something about him, wouldn’t it be wonderful? And that first opening sentence of, ‘Are you Janice Lee Cameron,’ was just an amazing moment in my life.

“You’ve got clear evidence, if you like, that they were a person, that they were alive.”

She will never forget seeing his name on the Roll of Honour at the Memorial when she first visited at the age of 34. “When I saw … my father’s name, I couldn’t stop crying,” she said. “It was again, there he was, he was a person, because when you haven’t got anything tangible to hang on to, no great big memories that are part of your life, and then you find, hey, here he is, well, it was fantastic.”

She placed a poppy next to his name and laid a wreath in his honour. “They gave me a pen and paper, and on it I wrote, ‘I wish we had more time together.’

“That had so much meaning for me, it was just fantastic. These are the things that you miss out on in life, but having … [the Last Post Ceremony] … and for him to be honoured in such a way is fantastic. It feels like something out of the blue and it really is the most wonderful feeling.”

In 2014 a combined civil and military team conducted a search of the Wessel Islands in an attempt to find her father’s grave and that of Milirrma Marika. And last year, Braund travelled to Yirrkala, near Gove, in Arnhem Land, for the dedication of a memorial to commemorate and honour the men who died 75 years ago. She will never forget the moment one of the traditional owners told her: “Your father is with us now. He is one of us. He has been lying next door to my people … and you are also one of us.”

“[It] was a great honour,” she said. “I have been asked, whether or not my father’s remains need to be repatriated, and I say no, because he’s with people who respect him and people who will always remember and look after him.

“[When he] said to me, ‘Your father is with us now, he is safe and he will never be disturbed, and he is one of us,’ it was a most beautiful moment. I’m so at peace now. I just know that he’s there. He’s in Australian soil. He’s with somebody … and they know that he is there, and he is one of them, and that’s a beautiful feeling. I don’t want him anywhere else, but there.”

Percy Cameron. Family photos: Courtesy Janice Braund.