'I can still visualise it now'

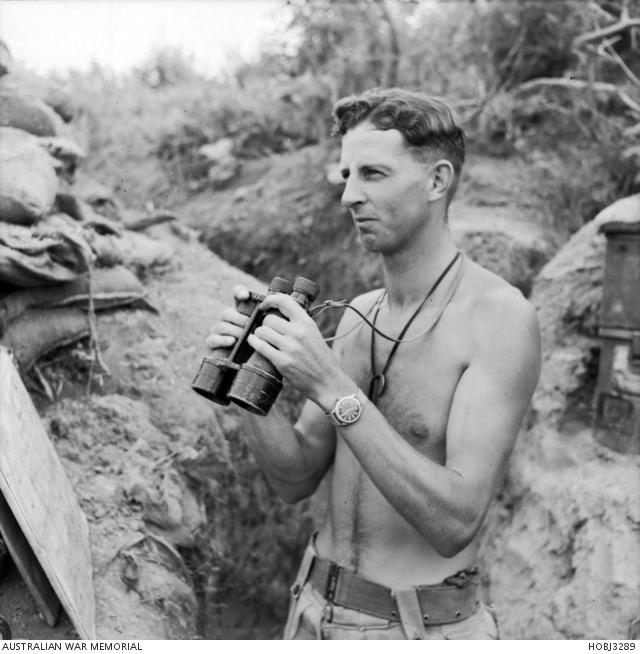

Colonel Peter Scott is lucky to be alive. In October 1951, the 22-year-old Peter was an intelligence officer during the battle of Maryang San.

“A lot of the other officers were just as young, if not younger than I was,” he said.

“There was artillery, bursting shells, and fights overhead, and it was just pandemonium really; dust and pieces of metal going in all directions.”

The fight for the strategically important Hill 317 was later described as “one of the most impressive victories achieved by any Australian battalion”, but for Peter it was one of the many close shaves he faced during his decorated army career.

“It was a big part of my life… and I can still visualise it now.

“It was very, very, successful and I think we got out of it very, very, well because we really stirred up the Chinese.

“They really hit back in the last couple of days, with artillery and mortars, just about blanketing the whole of that ridgeline.

“But sitting on top of 317 on the 7th of October, being shelled out of existence is the day that sticks in my mind.”

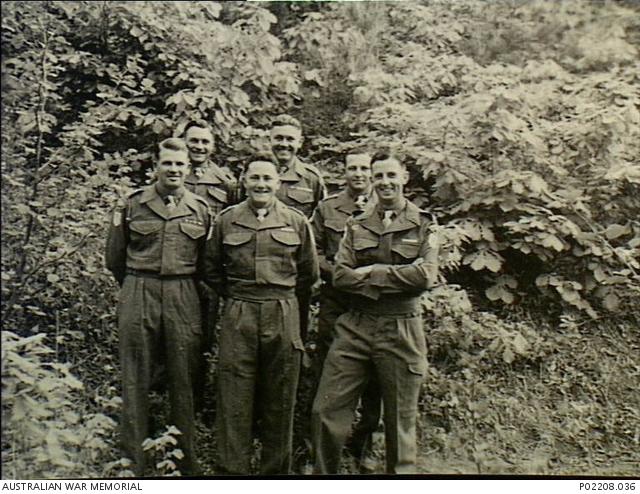

Informal portrait of the officers of 'A' Company, 3RAR, in a reserve area. The soldiers are back row, left to right: Captain Alexander Vogler (Alec) Preece, the company second-in-command; Major Jeffrey James (Jim) Shelton MC, the company commander; Lieutenant Lawrence George (Algy) Clark MC, on temporary attachment to the company. Front row: Lt Eric Robert (Bob) McCully, 2 Platoon; Lt Laurence Bonaventure (Laurie) Ryan, 1 Platoon; Lt Francis Peter Scott, 3 Platoon. Lt Ryan went missing presumed killed in action on 13 July 1952.

Francis (Peter) Scott was born in Melbourne in January 1929 and grew up during the Depression years.

“I went to school during the war and joined the cadet corps when I was about 13,” he said.

“I became a cadet lieutenant and applied for Duntroon in 1945. I was accepted in 1946, and so I spent the next three years in the Royal Military College, Duntroon.

“I was only 16 coming on 17 when I went in, and those were the average ages at that time.

“It was a bit strange because it was the first time I had been away from home – my family was in Melbourne and I was in Canberra – but I was really enthusiastic about it and I really enjoyed it.

“That was what I wanted to do and I never regretted it for one moment.”

Peter graduated from Duntroon in December 1948 and was posted to the 3rd Battalion, the Royal Australian Regiment (3RAR), then part of the British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF) in Japan.

“The battalion was in a place called Hiro, and I spent the next 18 months going to and from Tokyo,” he said. “We had to do training as well as guards of honour, and in fact, on a rotational basis, our platoons used to be responsible for the guarding of the Imperial Palace with the Americans, and also the British and Canadian and Australian embassies.”

Peter Scott, right, outside the Imperial Palace in Tokyo. Photo; Courtesy Peter Scott

He was in Tokyo when the Korean War broke out on 25 June 1950.

“The battalion was getting ready to come back to Australia when the North Koreans invaded South Korea,” Peter said.

“Unfortunately, I had an argument with a grenade while we were training, and so I then had to soft pedal for a while.

“I had taken my platoon out to do some live grenade throwing exercises and I ended up with one that didn’t explode. I had to do something about it – I couldn’t leave it there – so I used another grenade to put alongside it and then went back five feet or so to a little mound. I lay behind the mound, and the grenade I put down blew up. I then stood up, unfortunately, and the second one – the blind – went off, and it hit me in the right shoulder.

“The next day I was on a plane back to Australia, and I spent two or three months in hospital. It took me about 12 months to get back … and I went up to Korea in July 1951, and was there for 365 days.

“I went straight to a platoon and became a platoon commander.

“We were sitting on a feature called the Lozenge feature, which was just south of the Imjin River. It was in the middle of summer, so it was very, very, hot.

Senior personnel from 3RAR photographed at Battalion Headquarters during operations in the Korean conflict, possibly at the time of the Battle of Maryang San. Members of the group are, left to right: Captain H W 'Wings' Nicholls; Major J 'Jack' Gerke; Lieutenant Colonel F G 'Frank' Hassett, Commanding Officer (CO) of 3RAR; Major A F P Lukyn; Lt I R W 'Lou' Brumfield; and Lt J C Hughes; and Lt Peter Scott.

“We’d go out on patrol over the river, and see whether we could see what the Chinese were doing.

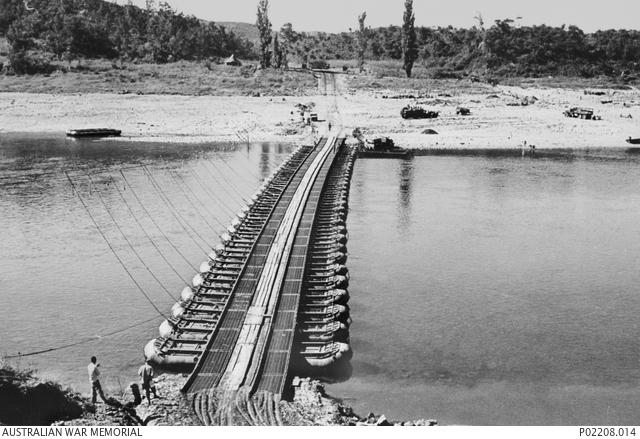

“The big problem there was that when it rained, the Imjin River used rise very, very, dramatically, so if you got caught in it, you were caught there for a day or so until the rain stopped and the river went down.

“On one occasion it rained, and we were absolutely stuck on the wrong side. We’d dug all our weapon pits, so we were sitting in our weapon pits up to our armpits when we were standing to, just hoping that the enemy wouldn’t come.

“Then about two months into my being a platoon commander, the CO wanted me to become his intelligence officer, and so I became his IO just a week or so before this major operation – Operation Commando – which was to capture two very, very, important hills overlooking the Imjin River.”

Korea. 1953-12-27. Aerial view of Lozenge feature (left and centre) running parallel with the Imjin River, occupied by the 3rd Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment (3RAR) in the Kansas Positions.

Imjin River, Korea, 1951-10. A pontoon bridge, code name Pintail, across the Imjin River.

The operation began on 3 October 1951 with a British assault on Hill 355, known as Kowang San or Little Gibraltar. Then, on the morning of the 5th, 3RAR attacked Hill 317: Maryang San.

“The US generals had decided that they needed to straighten the line and to prevent the Chinese from viewing what we were doing on the south of the river,” Peter said.

“The CO at the time was Lieutenant Colonel Frank Hassett; he was eventually Chief of the General Staff, and also Chief of the Defence Force. He was a magnificent officer; a real gentleman, and a very, very, efficient officer.

“He directed the battalion over these two hills – the first one in association with a British battalion –and then we went on our way, one company after the other, until we captured the hill which was called 317 or Maryang San, but then there were another couple hills we had to take to the west – Sierra and then ‘The Hinge’.

“We knew the enemy were there – we knew exactly how strong he was, and where he was – and gradually we continued through the advance, and through the preliminary hills and places that he was occupying.

“There was mist in the mornings coming from the river and that was a godsend in many ways because we were able to move in the dark and then move into the mist. It didn’t lift until mid-morning, by which time we were nearly on the enemy, and I think he was as surprised as we were.”

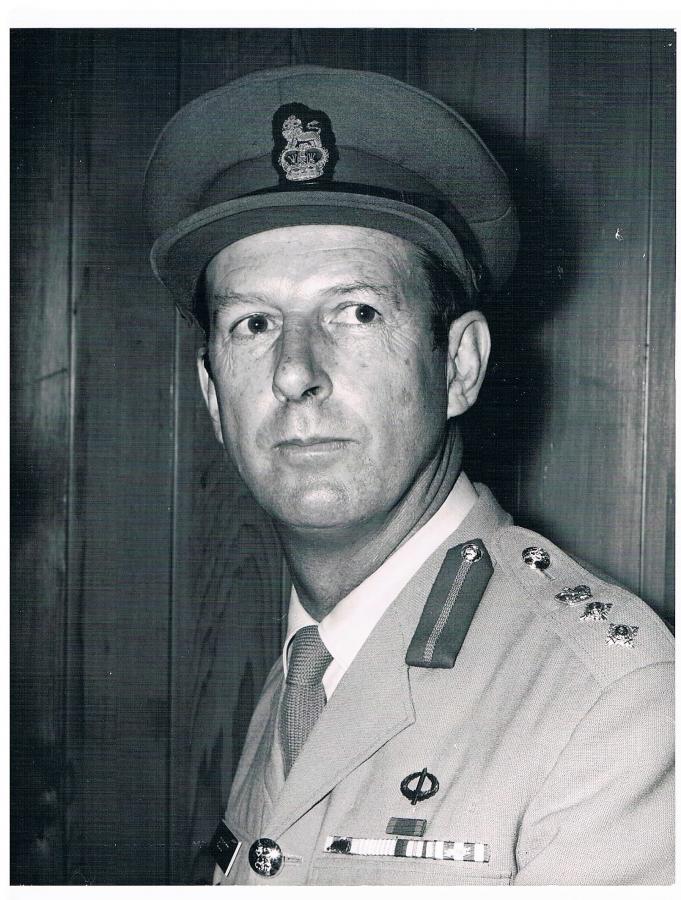

Lieutenant Colonel Frank Hassett in July 1951.

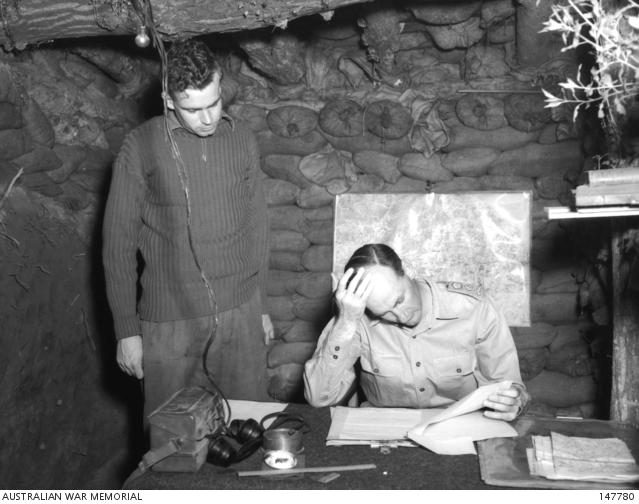

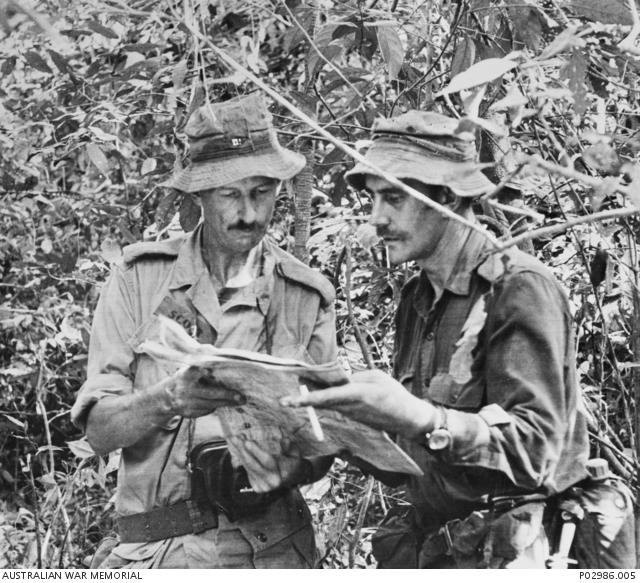

Lt Col Frank Hassett studying a paper given to him by Captain Lee Greville.

The battalion captured the first line of defences in a fierce burst of fighting, and the following morning drove the communist forces from their position atop the hill, but had to resist an enemy counter-attack. The crest of Hill 317 was secured on 6 October, after which the Australians assisted the British to take Hill 217.

“The enemy gradually realised that we were heading for him, so I don’t think he was very happy at all,” Peter said.

“When the battalion got on top of 317, or Maryang San, he wasn’t there; he’d decided to bug out. He was on the next hill, and then next one, so we went from 317, to Sierra, to ‘The Hinge’, and it was a really very, very, bad day, the 7th of October.

“The CO and his little party, which included me and the gunner battery commander, was sitting on top of 317, and getting the living daylights bombed out of us – I don’t how we survived – but luckily we did, and Colonel Hassett, was awarded an immediate DSO.

“It was very, very, hilly, and very, very, rough, with rocks and boulders, and lots of trees and undergrowth, so it wasn’t a picnic by any means. It was very, very, difficult, and of course the soldiers, they were running up these hills with their bayonets fixed and throwing grenades.

“We had a whole division of artillery support so that we could concentrate it, and on one occasion we had the whole divisional artillery firing in, just in front of the battalion on top of 'The Hinge' and Sierra, and then of course, the Chinese, reacted in about the same sort of strength with artillery fire and mortars.

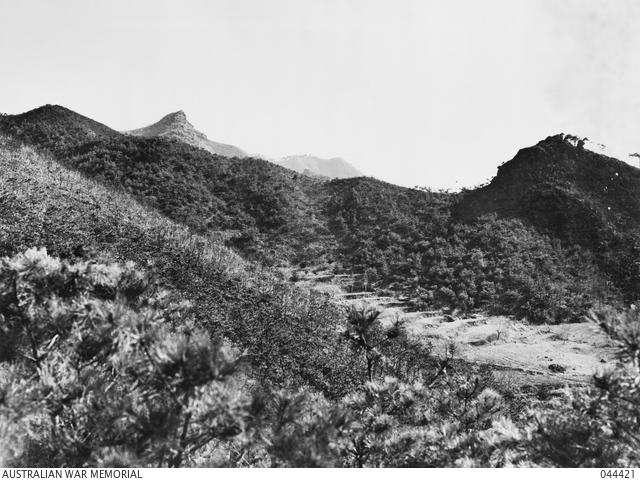

Hill 317 (Maryang San) captured by 3RAR during Operation Commando.

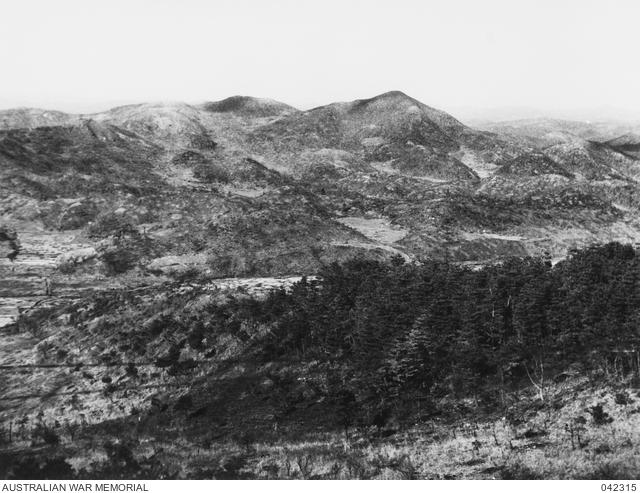

View of Hill 355 or 'Little Gibraltar' taken from Hill 210 looking north.

View from a forward platoon position on the northern side of Hill 355. Hill 317 (Maryang San) is the highest pyramid shaped hill to the right of the picture.

“My head was down looking after the maps and the radio. We – the CO and I and a couple of others – were occupying the enemy trenches on top of 317, so I was sitting well down under cover while all this artillery and mortars were coming in. That’s why we were so very lucky that we didn’t get a direct hit; otherwise, the battalion headquarters, and the CO, and I, and the battery commander would have all been eliminated very easily.

“The CO was dashing around everywhere, and I just had to sit there with his radio set, and be making sure we were in communications with the forward companies and the battalion headquarters back about two or three thousand metres. I can’t remember how scared I was, but I certainly was scared, that’s for sure.

“Then on the morning of the 8th of October, [the Chinese] mounted some very, very, successive attacks, preceded by mortar and artillery fire, mainly onto the position on ‘The Hinge’.

“We got a lot of casualties out of that artillery fire, and [the Chinese] tried three times to overcome the company on ‘The Hinge,’ but they certainly didn’t – they couldn’t dislodge them – and so the next day, we handed over to a British battalion, and we withdrew to the east and tried to get some rest and sleep.”

Weeks later, Maryang San was recaptured by the Chinese. It was a terrible blow for those who had fought long and hard to capture it. It would remain in the hands of Chinese forces for the rest of the war. Of the Australians who had served in the Battle of Maryang San, 20 died, and 104 were wounded.

Group portrait of officers who attended Colonel Frank Hassett's 34th birthday party. Back row: Captain Lee Greville, (3RAR); Major Bill Finlayson; Captain Peter Francis, Royal Engineers; Lieutenant Colonel Hassett DSO OBE (4th left); Major Jeffrey J. (Jim) Shelton; Lieutenant Colonel Patterson, 16th Field Regiment, Royal New Zealand Army; Major David Thomson; Arthur Roxburgh (part obscured, at rear); Major B. Hardiman (holding beer stein); Lieutenant Peter Scott (far rear); Major Nichols (holding beer stein); John P. White (far rear); Regimental Sergeant Major Hart; Captain Tom Gibson (far right, at rear); Major H. Hind; Captain B. Crosby. Front row (all kneeling): Captain W. Reg Whalley; Lt R. Fred Gardiner; Lt Maurie B. Pears; Lt Roy Pugh, and Lt Angus Waring, 5 Enniskillen (Inniskilling) Dragoon Guards.

A 17-pounder anti-tank gun engaging enemy positions. Photo: Courtesy Peter Scott

Peter was Mentioned in Dispatches for his role in the battle, and later took command of an anti-tank platoon.

“They didn’t have an anti-tank platoon, so I asked the CO if I could bring up one of the anti-tank guns,” he said. “It was a 17 pounder, and we used it to harass the Chinese… We’d stir them up every day, but when the reaction came, the rest of the battalion had to suffer that as well.”

Another battle the men face was incredibly harsh weather conditions, the likes of which they had never seen before.

“There was a lot of snow, and the cold was very, very, cold,” Peter said. “We used to call it ‘frozen chosen’, and a few soldiers either shot their finger off, or shot themselves in the foot, just to get out of the cold. A self-inflicted wound was a court-martial offence … but we were constantly in contact with the enemy right through until I left in July 1952, and that continued really until the ceasefire in July 1953.”

Korea, c. 1951-01. Carrying his rifle on his shoulder and wearing a greatcoat and pile cap against the winter cold, a member of the 3rd Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment (3RAR), stands on a traditional Korean footbridge and stares into the frozen waters of the Han River. Beyond the soldier, the ice-bound river stretches away to a plain and hills covered in snow.

Peter went on to command 3RAR from 1969 to 1971, including an operational tour of Vietnam for which he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order, South Vietnamese Cross of Gallantry with Palm, and US Army Commendation Medal. Later appointed Military Assistant to the Minister of the Army, he was promoted to colonel as Services Attaché to Pakistan and Afghanistan, and was Commander of the 2nd Military District, Sydney, before retiring in 1983 after 37 years’ service.

Lieutenant Colonel Peter Scott, Commanding Officer of 3RAR, briefs Major Peter Leach Tilley, Officer Commanding C Company, 3RAR, in Vietnam.

Lieutenant General Tom Daly, Chief of General Staff, left, and Lieutenant Colonel Peter Scott, Commanding Officer of 3RAR, second from left, chat to an unidentified soldier in Vietnam.

He returned to Korea in 2016 for the 65th anniversary of the battle of Maryang San and is now patron of the South Australian arm of 3RAR Association.

“I didn’t even think of going back earlier … but I went back with seven other veterans and it was a marvellous trip,” he said.

“We went to the cemetery down in Busan, and there were all the graves of all the fellows that we lost in Maryang San. There were others I knew too, including two of my classmates from Duntroon.

“Then we went up north, right up to the ceasefire line. We were right on a point overlooking the Imjin River, and probably three or four thousand metres away was 317.

“It was very quiet and peaceful there, and 65 years after I’d been sitting on top of it, I saw it again, so it was very, very, emotional.

“It was generally the forgotten war as far as the general public was concerned, but we didn’t forget it, and the families didn’t forget it.”

Colonel Peter Scott DSO, right, in Adelaide with Colonel Don Beard AM RFD ED, who was the RMO with 3RAR at Kapyong.

Today, Peter writes books about his experiences and still considers himself to have been fortunate to have survived.

“I’ve probably had three lives, but I’ve used them all up now,” he said.

“I was shot down in Vietnam, which I suppose was just another close shave of mine; the grenade was the first close shave; and then being on the top of 317 was the second; but the third one was really being shot down in a helicopter. And when I add those three things up, I think, ‘Gee whiz, I did have somebody guiding me,’ and I was very, very, lucky to have got out of it – all three of them.

Colonel Peter Scott DSO pictured in uniform in about 1970. Photo: Courtesy Peter Scott

“Today, the greatest joy for me is to meet up with my soldiers again. I go along and shake everybody’s hand… Sometimes they call me Sir, sometimes they call me Scotty, sometimes they call me Colonel … and some of them, even now, ring me up, and say, ‘How are you digger?’

“I have the greatest respect for every single one of them.

“It’s a big part of my life – in fact, it was my life – and it’s been my life, right from the time I went to school; I’ve never known anything else.

“I would never say I wouldn’t do it all again, because I would – I most certainly would.”