'In wars where nothing seems to matter, I can take pictures in which every person counts'

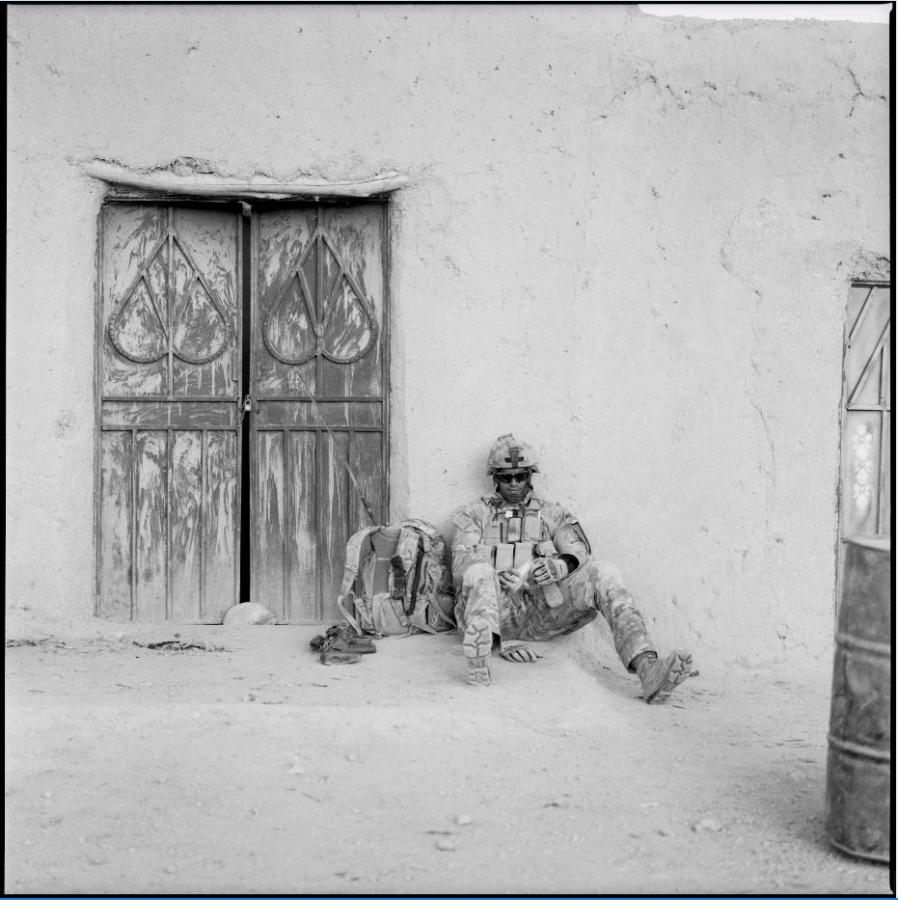

Australian soldiers during a quiet moment while out on patrol in Afghanistan in 2011. Photo: Gary Ramage / TPR Gallery

Gary Ramage admits he’s seen too much death. As a former soldier and one of Australia’s leading news photographers, Ramage has been in and out of war zones for more than 20 years.

From mass graves in Kosovo, to a young girl crying in Somalia, and a soldier and his dog sleeping together on the ground for warmth in Afghanistan, Ramage’s images capture confronting and moving moments in war as he returns again and again to the front line to tell the stories of the men and women who can’t speak for themselves.

“I have seen things that I can’t unsee,” Ramage said. “[But] I can get through by reminding myself of the simple rule I live by: in wars where nothing seems to matter, I can take pictures in which every person counts.”

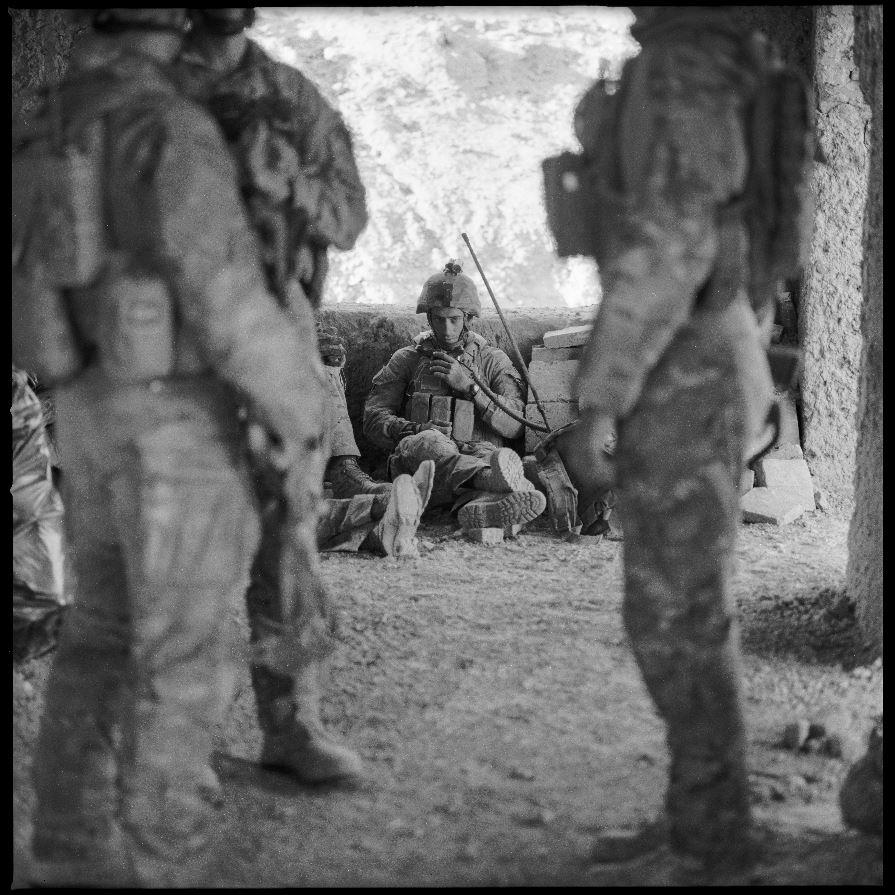

One such picture is what he calls the “archway picture”, which has been chosen to represent modern-day Australian forces in the lead-up to Anzac Day commemorations at the Australian War Memorial. Part of a collection of black and white photographs Ramage took while embedded with Australian soldiers in Afghanistan in 2011, the picture shows members of Charlie Company, 2RAR, during a quiet moment while working out of a remote US Special Forces base in Uruzgan Province.

“We’d stopped in this location outside of a village and the guys were sleeping in this mud hut,” he said. “It was very calm, and the guys were obviously relaxing and chilling out … They’d accepted me as part of their patrol and … that was just one of the lucky pictures that I took that day, where they were just ignoring me and going about their daily routine.

“The guys were exhausted – they’d been out there for months on end, and it was a … nice moment where they were just relaxing as if there was nothing that could harm them anywhere. But there was. That area had just been cleared the night before by American Special Forces.

“It’s not your typical bang-bang picture with blood and guts and gore and fighting; it’s the other side of what it is that the soldiers do. It’s caught them in a moment which you normally don’t get to see because they are … always ready in case something happens.”

Gary Ramage donated his Hasselblad camera to the Memorial. It is now on display in the Afghanistan galleries.

The photograph was taken on film using an old Hasselblad camera, which Ramage later donated to the Memorial and is now on display in the Afghanistan galleries.

“It’s the same as the camera they used on the moon for the first moon landing … and back in the day it was very high end,” he said. “It’ll probably last forever, so it’ll be there long after I’m gone.”

The collection of images is now being used by the Memorial to help tell the stories of Australian men and women serving in Afghanistan, and the archway picture will be used in commemorative brochures and booklets for Anzac Day.

“I’m very proud of what I achieved over there, but I wouldn’t have been able to do what I did photographically without the diggers on the ground or the soldiers from that unit,” Ramage said.

For Ramage, telling their stories is what it’s all about. “It’s part of our national history, and we need to cover what it is that the soldiers do on our behalf,” he said. “Obviously they volunteer, but they get sent out to these countries to try to make a difference. I believe that we should be telling their stories as part of our military history so that you can go into our Memorial and generations of younger and future Australians can look back and see what it was that these guys did in Afghanistan. It’s very humbling … [and] it’s a huge privilege for me.”

Ramage first became interested in photography as a child when he started playing with an old 35mm camera that somebody left in the back of his father’s taxi in Scotland before the family moved to Australia.

“I was always playing with cameras,” Ramage said. “Mum and dad came out here as part of the ten-pound program back in the seventies, trying to find a better life for us… and I think dad had a bit of an adventurous streak in him.

“He had a hand-crank cinecamera that he filmed us growing up on … [and] he was always out there filming family events and us riding our bikes out in the cul-de-sac… I guess it just sort of rubbed off on me without me really knowing it … and, for whatever reason [that] sent me down that track.”

An Australian soldier resting in Afghanistan in 2011. Photo: Gary Ramage / TPR Gallery

Ramage still has his father’s movie camera and projector, but at the time, he never thought seriously about photography as a career. “I don’t think I really had any aspirations as a kid,” he said with a laugh. “All I thought about was sport. That’s one of my biggest regrets, that I didn’t finish high school. I pulled the pin because I was a very frustrated young teenager and very angry at the world… Mum and dad moved around a little bit … and I just rebelled.”

Ramage jokes that he joined the army when he turned 18 “to get away from my parents”.

“It’s stupid really,” he said with a laugh. “I guess I inherited my father’s sense of adventure as well… But it wasn’t until a lot later in life that I realised my family has always served. My dad did his reserve time, and my grandads all fought in World War I, so there’s a lot of history there, and whether you call it destiny, or whatever, I just fell into it.”

Ramage was serving with 6RAR in Brisbane when an opportunity came up to be the battalion’s photographer. “I was doing just your basic infantry stuff, and I wasn’t very good at it,” he said, smiling. “A friend of mine was getting out [of the army], and he put my name forward because I’d always had an interest in photography at school. I just more or less fell into it … and I joined the Public Affairs Corp, and never looked back … Again, I landed on my feet.”

Ramage is now the chief photographer for News Corp, covering federal politics as well as national and international news, but remains passionate about documenting soldiers’ stories.

“I’ve still got a soft spot for the military and that’s why I kept going back to Afghanistan to cover the ADF … because that’s what I was passionate about,” he said. “The war stuff, if you want to call it that, is for the guys that are out there … I thought that everyone had the right to know what these guys are doing and why they’re over there fighting and dying for us.

“It’s … all about getting that one picture that can tell a story and inform people. That’s the way I was taught, and I guess that’s just sort of stuck with me.”

A member of Charlie Company, 2RAR, pictured in Uruzgan Province in 2011. Photo: Gary Ramage / TPR Gallery

A triple Walkley award-winning photographer, Ramage has documented conflicts around the world, including Somalia, Bougainville, Bosnia, Kosovo, East Timor, Iraq, and Afghanistan. He has been alongside Australian soldiers on the ground during rocket attacks and firefights, and helped medics in the back of a helicopter trying to save a dying American soldier’s life. He remembers seeing Afghan doctors covered in blood as they amputated a wounded man’s legs, and being at a hospital in Kandahar when 17 casualties came in.

“There was one little boy who died there, and it was very heartbreaking,” he said. “I listened to this little boy screaming his lungs out because he was in so much pain.

“The worst times are always afterwards, when you actually have time to process what’s actually happened and what you’ve photographed … because normally, when the camera is up in front of you, it’s real, but it’s not. It’s like a little barrier, like a little safety blanket.

“When I was younger it used to affect me quite a lot because I didn’t know how to deal with it ... But because I’ve done it for so long now and seen some bad stuff, it just gets processed and pushed deep down, and normally it doesn’t bother me. It’s only every now and then that you get a bit of a wake-up call, whether it be a song, or a smell, or whatever, that will trigger a memory, but you just deal with it …

“If I get a bit sad or whatever, I go and do something, and I keep myself occupied. I have a lot of different hobbies, and that keeps me going without turning to the bottle or drugs or whatever to try and suppress the bad memories and the bad thoughts or whatever… But everybody’s different.

“I don’t dwell on it, because if you dwell on it, it will just eat you up from the inside out. You’ve got to live, so I just put it down to one of life’s experiences and move on to the next chapter. If you let it get on top of you, it will just eat you up.”

Australian soldiers pictured in Afghanistan in 2011. Photo: Gary Ramage / TPR Gallery

Since the publication of Afghanistan: Australia’s War, a striking visual record of Australia’s role in Afghanistan with words by Ian McPhedran, and The Shot, a book written with Mark Abernethy that tells the story behind the pictures, Ramage has spoken at writers’ festivals and events about his work. But he admits that he doesn’t really like being in the spotlight. “I’m behind the camera, and that’s the way I’ve always done it,” he said. “When you go out there, no one’s hassling you. Phones don’t work. Internet doesn’t work. You just go out there and take pictures.”

At 50, Ramage still keeps his camera gear in his car “all gaffer taped up” to protect it and plans to keep taking photographs and telling soldiers’ stories as long as he’s able.

“Obviously I’d still want to go, but you’ve got to be sensible about this – there’s no point being out there if you’re going to weigh people down,” he said. “[But] I’m not really into the term combat photographer, or [the] war photographer title. I’m a photographer, and I take pictures. That’s it … I’m getting paid, at the moment, to do my hobby … and I’m very lucky to be in the position that I’m in … I can’t complain about anything.”

Gary Ramage’s images have been chosen to represent modern-day Australian forces in the lead-up to Anzac Day commemorations at the Australian War Memorial and will feature in commemorative brochures and booklets. The images will also be projected onto the building before the Dawn Service on Anzac Day.

The Hasselblad camera Ramage used to take the photographs was donated to the Memorial and is now on display in the Afghanistan galleries.

Afghanistan: Australia’s War and The Shot are available from the Memorial shop.

See more of Gary's work at www.tprgallery.com.au

Gary Ramage in Iraq: "The war stuff ... is for the guys that are out there." Photo: Courtesy Gary Ramage