Queen of the desert

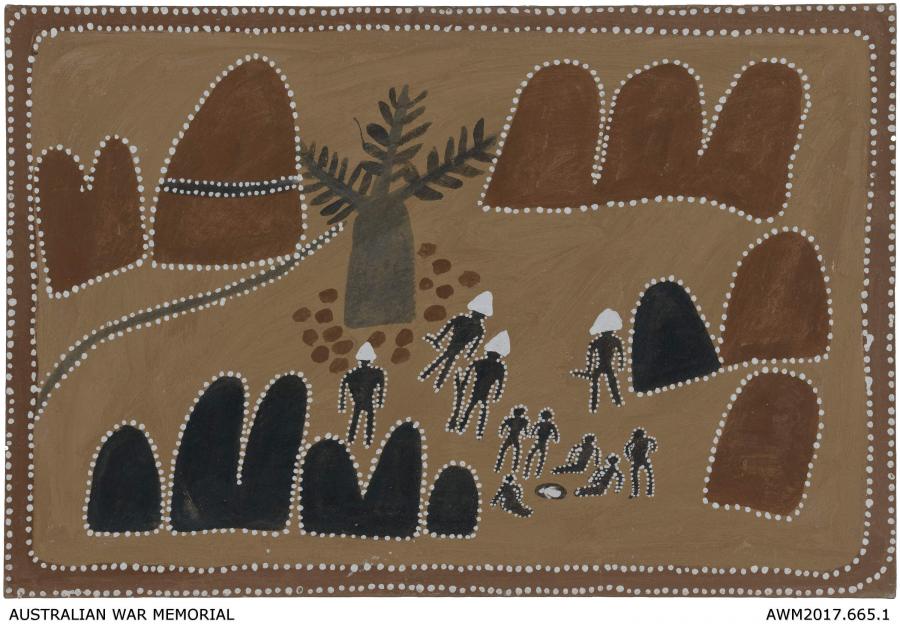

Horso Creek Killings by Queenie McKenzie, 1996. AWM2017.665.1 Copyright the Estate of Queenie McKenzie.

As Queenie McKenzie’s work Horso Creek Killings goes on display at the Australian War Memorial, Claire Hunter looks at the story behind the artist and her painting.

“Every rock, every hill, every water, I know that place backwards and forwards, up and down, inside out. It’s my country and I got names for every place.” -- Queenie McKenzie, artist.

When artist Queenie McKenzie was a child her mother would rub charcoal into her face in an attempt to darken her features so the authorities wouldn’t take her away.

The child who had been nicknamed Garagarag or Blondie because of her light skin and fair hair was born in 1916 at Old Texas Downs on the banks of the Ord River in the remote and rugged East Kimberley in Western Australia. The daughter of a Malngin/Gurindji woman and a white horse breaker, she only escaped the Australian government’s assimilation policies of the time because of her mother’s desperate efforts to conceal her background.

Queenie went on to become a respected artist and a prominent and compelling commentator on the Aboriginal experience. Her work Horso Creek Killings (1996), which tells the story of the Horso Creek Massacre in the 1880s, is now on display at the Australian War Memorial.

This important work complements the Memorial’s current exhibition For Country, for Nation, which highlights the longstanding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander tradition of protecting Country, including ritual, performance, painting, and fighting.

Memorial Director Dr Brendan Nelson said understanding the perspective of Indigenous people demanded a deeper sense of cultural perspective.

“When the First World War broke out, despite being prohibited from enlisting, at least 1,500 men of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander background enlisted to fight for the young nation that had taken so much from them,” Dr Nelson said.

“Their determination to serve and fight for Australia only four or five generations after the First Fleet arrived, existed despite the history of dispossession and violence perpetrated against them.

“Much of this is depicted in the Memorial’s exhibition For Country, for Nation and assists us to tell the story of Indigenous Australian service overseas and at home.”

The Horso Creek Massacre has been described as one of the most horrific and defining events in Aboriginal/White relations in the Kimberley region of Western Australia. The story of how a group of Gija people were shot and killed by white men for driving off bullocks has been passed down through the generations by word of mouth and Queenie learned of the story from her grandfather, Paddy Rattigan. Paddy’s father had killed a bullock and the white men were brutal in seeking their retribution. One old woman, not understanding what they were, is said to have given the men a bullet she found, which they then shot her with. The victims’ bodies were later burnt to hide the evidence. One boy managed to escape by hiding in the dead body of the animal and was later found by his mother. He was the sole survivor of the massacre.

Displayed next to Queenie's work is a painting by her life-long friend Rover Thomas. The pair met while Thomas was working as a stockman. He’d been kicked by a horse, and scalped. Queenie, who worked as a goat herd and a cook on cattle stations for almost 40 years, stitched his scalp back on using a needle and thread. Years later, Queenie saw the success Thomas had with painting and decided she too could paint the stories of her life and her country.

She only started painting when she was in her 70s and was the first woman in her community to do so. Until her death in 1998, she examined everything from the creation of the world through to the violence of the colonial era and her paintings reveal an intimate knowledge of the country, explored through landscapes and dreaming.

Queenie McKenzie’s work is now on display at the Australian War Memorial. The For Country, For Nation exhibition is on until September 20.