Radio propaganda and the kindness of strangers

In 1944, Yvonne Jobling was a schoolgirl studying shorthand. Every evening at her home in Geelong, Victoria, she practiced her shorthand by listening to the radio. On Friday, 17 March 1944, she happened to be listening to the short-wave broadcast of Radio Tokyo, and heard messages from Australian prisoners of war.

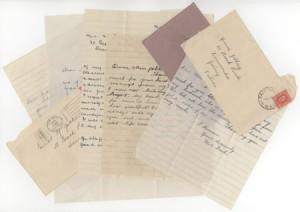

Collection of letters sent to Yvonne Jobling, March 1944 (PR04494).

Jobling took the messages of five prisoners of war, and sent them to their families across Australia. A few days later families in Katoomba (NSW), Fairfield (NSW), Petersham (NSW), Adelaide (South Australia) and Sunshine (Victoria), received these welcome messages. Each family responded with deep gratitude. Mrs Barber of Petersham thanked Yvonne for her kind letter, and told her that ‘my heart has been aching for news of him’. Nancy of Adelaide, sister of Robert Louis Whitington (SX8121), wrote: ‘If you have a friend or brother a prisoner I sincerely trust you have received news of him ‘ere this.’

These letters have recently been received by the Australian War Memorial in a generous donation from Yvonne (Private Records Collection PR04494). They form a small collection that speaks eloquently of the kindness of strangers on the home front during the Second World War, and the capacity of such kindness to bring hope to anxious families.

Messages from prisoners of war became a regular and integral feature of Japanese propaganda efforts, beginning in 1943. Radio Tokyo, along with stations in Batavia (Jakarta), Saigon, Shanghai and Singapore — all stations of the Japanese Broadcasting Corporation (NHK), an important part of the Japanese war machine — broadcast the messages alongside so-called ‘news’ in an effort to lure listeners, and further the general aim of disheartening a war-weary nation. Indeed, broadcasts were made in many languages, and intended for soldiers and civilians alike.

The Japanese took care, unlike their German counterparts, to announce the service number, name and regimental details of the prisoner whose message was being announced. It also seems that most of the messages were genuine, another strategy to keep Australian audiences listening. During the course of the war, however, the Japanese began subtly editing the messages to include stock phrases about good food and good living conditions, hoping Australian audiences would be fooled by these false hopes. Unfortunately, and perhaps deliberately, some messages were read months after writing, which led to confusion and false hopes on the part of families who had already received word that their relatives were dead.

As with all propaganda, these radio broadcasts were all made in the hope that Australians might be deluded into accepting the expansionist desires of the Japanese. And as with most propaganda, the target audiences were usually unreceptive. Australians took heart from the messages, but were advised by their government that all messages should not be accepted at face value.

Even if the messages Yvonne heard were only partially the works of Australian prisoners of war, her action in transcribing and posting them to the families around Australia was a truly kind and generous act.