Rain and Mud: the Ypres - Passchendaele Offensive

View of the swamps of Zonnebeke on the day of the First Battle of Passchendaele. E01200

When considering the Battle of Passchendaele in 1917, what immediately springs to mind is a desolate, shattered landscape of mud. So when looking through the photographs of this battle here on the blog, and in the exhibition, it may be puzzling that some depict this morass with men and horses up to their waists in mud, yet many others show a rather dry and dusty landscape. The answer is that this was a lengthy campaign (July to November), and the weather conditions proved quite changeable and fickle. The same applies to the Somme Offensive which ran for a similar period during the previous year. The other factor at Ypres was the physical characteristics of this part of Flanders. The water table in this area is very high and indeed parts of the battlefield were swamp or reclaimed swamp. So even when the surface appeared dry, it could in places be sodden below the crust and digging into the ground even to a shallow depth would invite water. Naturally the blanket coverage of shell craters only made the situation worse.

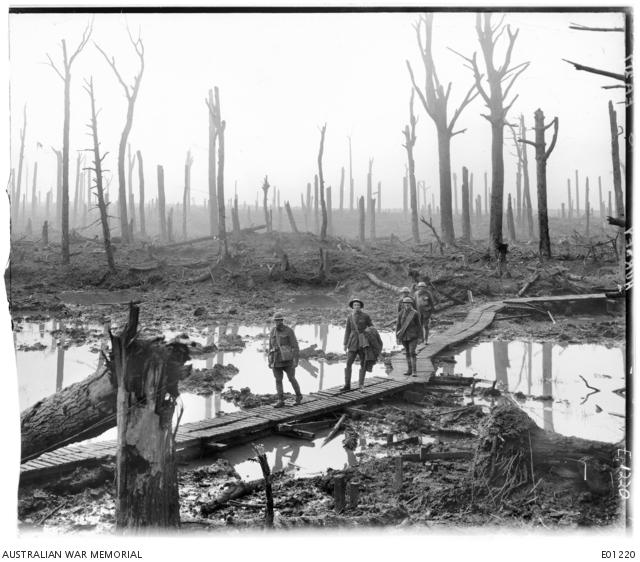

Australians crossing Chateau Wood via duckboards in October 1917. E01220

Bringing supplies up through the mud. E00963

According to Robin Prior and Trevor Wilson in Passchendaele: the untold story (p 97), during August 1917, 127 mm of rain fell in Flanders, which was double the normal average for that month. October also proved another very wet month, with 30 mm of rain falling in just the five-day period 4-9 October (pp 126, 159). However the month of September was mostly dry and this coincided with the three major pushes that the Australians spearheaded in the Ypres sector (Menin Road 20 Sept, Polygon Wood 26 Sept, and Broodseinde 4 Oct). During these attacks the troops marvelled at how strong and utterly dominant their supporting artillery fire was.

Ammunition columns moving up to the front via the dusty Poperinghe Road, 30 September. E00871

Men of 45th Battalion on Anzac Ridge, 29 September. E00839

HQ 24th Battalion on Broodseinde Rigde, 5 October, E04513

But in the afternoon of 4 October, right after the Broodseinde operation had been completed (it was over by noon), the weather broke and the rain set in, quickly turning the devastated battlefield into a quagmire. In these conditions it was impossible to drag forward enough artillery and ammunition to maintain such strong support. So the troops that attacked in the wet after 4 October noticed a dramatic drop-off in supporting artillery fire to the point where at times it was barely noticeable. Another pitiful result was the greatly increased difficulty of evacuating the wounded. The decision therefore to continue the offensive and capture Passchendaele in the rain and mud was a weighty one. As C. E. W. Bean later wrote,

‘In these circumstances Haig made the most questioned decision of his career.' (Bean, Vol IV, p 883).

Men of 39th Field Artillery Battery hauling a gun through the mud, 30 October. E01240

Interestingly, at this point Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig acknowledged the weather and terrain problems, telling war correspondents on 11 October:

‘It was simply the mud which defeated us on Tuesday [9 October]. The men did splendidly to get through it as they did. But the Flanders mud, as you know, is not a new invention. It has a name in history - it has defeated other armies before this one...' (quoted in Bean, Official History, Vol IV, p 908).

One wonders with this admission of the difficulties presented, why Haig then persisted with the offensive. However it must be considered that there were real dangers in halting the offensive where they stood. They were still short of the final ridge at Passchendaele and had they remained short of it, it would have been very difficult and costly in lives to hold such a poor position. So perhaps it can be argued that the final push to capture Passchendaele through the dreadful mud of October and November was a combination of this tactical necessity, Haig's perception of an imminent German collapse and his desire to see his grand plan through to a successful conclusion.

For the Germans the onset of rain was a Heaven-sent. Indeed Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria, the Field Marshal in command of the entire northern sector of the Western Front (i.e. that principally opposing the British and Commonwealth forces), made a relieved note in his diary;

12 October 1917

'Witterungsumschlag. Erfreulicherweise Regen, unser wirksamster bundesgenosse.'

(trans. Sudden change of weather. Most fortunate rain, our most effective ally).

Generalfeldmarschal Rupprecht, Crown Prince of Bavaria. H12371

It should also be remembered that despite these dreadful conditions and the grievous losses, the British Army and its Commonwealth troops did succeed in capturing Passchendaele and part of the final ridge. It was the Canadian Corps that finally achieved this on 6 November. The Canadians would by 1918 become past masters at providing massive artillery support for their infantry, but in the mud before Passchendaele in November 1917, these techniques they were trying to perfect must have been greatly frustrated. With this in mind, their capture of Passchendaele is all the more impressive.

Finally, in one of the war's ‘what ifs', it may well be speculated that the offensive at Ypres during 1917 might have succeeded had it gotten underway several weeks earlier, and the final ridge at Passchendaele been captured in early October, before the weather really broke. One can only wonder...