Rare postcards shine a new light on Indigenous soldiers service

On a cold Sunday morning in late May 2024, Jeannie Lister and her husband Ron came across a stall specialising in antique and vintage wares at Bendigo Showgrounds market. Inside a glass display cabinet she saw three silk embroidered postcards that caught her eye.

The postcards were colourful silk patterns of flowers and birds with Christmas and New Year messages. One featured flowers of red, silver, gold and blue with the words “A Kiss from France” written in silver silk thread between a Union Jack and red poppy.

With her love of embroidery and an interest in local and family history, Jeannie immediately recognised them as First World War souvenirs sent home by soldiers on the front lines.

“The postcards stood out because of the intricate embroidery and I felt immediately drawn to them,” Jeannie said. “I knew that during the First World War, women in France sold postcards like these to soldiers going to the front lines.”

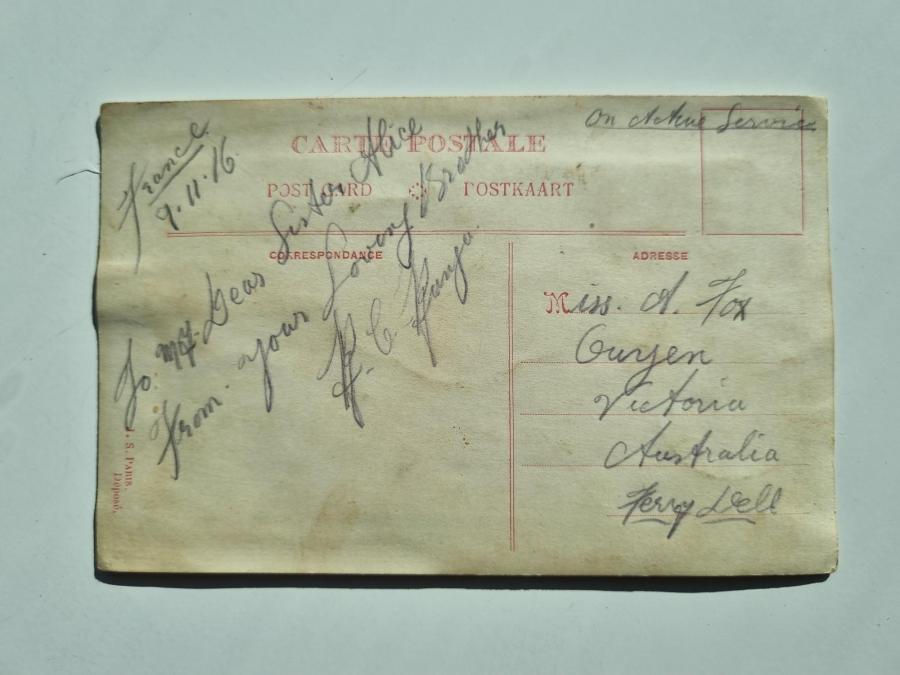

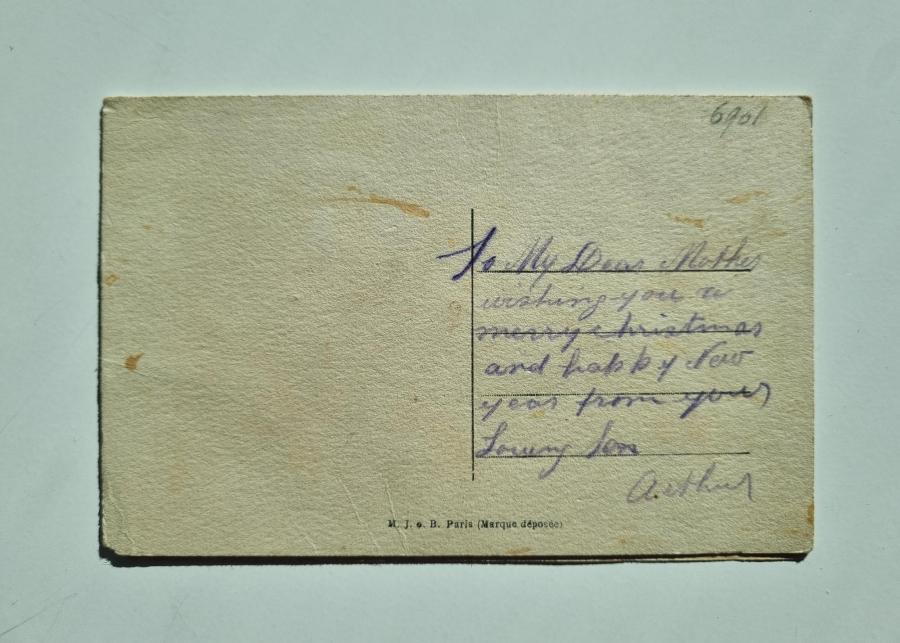

Jeannie paid ten dollars for each of the three postcards. As the stall owner took them out of the display cabinet Jeannie realised the postcards had writing on them. There were messages of love sent home to a sister and father, but the name of the sender, signed in cursive script, was unclear.

The name of the recipients was easier to decipher, Alice and S.D. Fox of Ouyen, Victoria.

“I decided that if I could trace the Fox family, I might find an interested family member to send them to. I knew that if they were from someone in my family, I’d love to have treasures like this find their way home to me,” Jeannie said.

Three embroidered postcards from the First World War.

Jeannie found a family tree of Alice Fox on a family history website. She traced Alice’s family and saw that she was half-sister to a man by the name Raymond Charles Runga. Jeannie was then able to decipher one of the signatures as ‘R.C. Runga’. The other postcard was written by his half-brother, Arthur Henry Fox.

“Now I was certain I had the right family,” said Jeannie. “I was excited to see how much I could find out about them.”

With some experience as an amateur historian, Jeannie began to fill in the details of the life of Raymond Runga and his brother, Arthur Fox. She soon realised she had stumbled on wartime correspondence of significant Indigenous soldiers.

Raymond Charles Runga, known as Charlie, was born to Charles and Eliza Runga in Naracoorte, South Australia, in 1889. His father was highly respected in the local community and worked as a railway ganger.

Following the death of Charles, Eliza married another Aboriginal man, Samson Daniel Fox, and moved to Victoria. Eliza and Samson had three children together: Samson Daniel Fox Jr, Arthur Henry Fox and Alice Fox.

At the outbreak of the First World War the three brothers were among approximately 1200 Indigenous Australians who enlisted, or attempted to enlist, in the armed forces. Military service during the First World War was restricted to those described as being of ‘substantial European descent’ and many Indigenous Australians were rejected because of their ancestry.

Charlie Runga was recorded as being of ’Black (aboriginal) complexion’ on his enlistment papers and his two brothers as ‘Dark’, but their heritage was overlooked and they were accepted into the AIF.

Samson was the first to reach the front lines. He arrived on Gallipoli towards the end of the campaign, landing in November 1915 and staying until the evacuation in late December. He was then sent to France, where he fought in the battle of Pozières, witnessing the deaths of thousands Australian soldiers torn apart by the destructive power of artillery.

Samson’s luck ran out in May 1917 when he joined a raiding party near Ploegsteert in Belgium and was among 30 Australians killed while attacking an enemy trench.

Unlike Samson, Charlie and Arthur survived the war, but were far from unscathed.

On enlistment Charlie was assigned to the 6th battalion and Arthur to the 38th. They arrived on the front lines in France in late 1916, shortly after the battle of Pozières and spent their first months of active service in the bitter cold of the Western Front. It was during this period that the brothers sent home the postcards that Jeannie would find in a Bendigo market over 100 years later.

“The sweet postcards, sent by these Indigenous soldiers to their much-loved family in the dry Victorian Mallee – a world away from the horrific battlefields of First World War France and Belgium – show us, with touching poignancy, the soft side of brave young men who served and sacrificed with distinction for their country,” said Jeannie Lister.

Arthur was the victim of a gas attack at Ypres in June 1917, from which he contracted pulmonary tuberculosis. He lost a significant amount of weight and suffered severe coughing fits which ultimately led to him being declared an invalid and unfit for active service.

Charlie, meanwhile, contracted scabies, probably from the lice that infected the trenches, and was hospitalised for several months. He returned to the front lines and was shot in both arms in fighting near Passchendaele in October 1917.

After another stay in hospital, he returned to the front in 1918. In August he performed acts of heroism for which he was awarded the Military Medal, the third highest award for bravery. The citation for the award reads:

“When the left portion of his Company came under exceptionally heavy machine gun fire from a wood in front, Pte Runga, taking charge of a small party dashed forward to the wood and succeeded in capturing two hostile machine guns and their crews of 16 men. On another occasion he rushed forward alone over 70 yards of ground without cover and despite point-blank machine gun fire succeeded in bombing the enemy from the communication trench, thus enabling the remainder of the platoon to continue their advance. This latter feat was a heroic example of utter disregard of personal safety and the desire at all costs to worst the enemy, any man of whom with one shot calmly aimed could have killed him.”

Charlie was gassed in fighting three days after his acts of heroism, but survived the war. He finally returned to Australia in September 1919 and was presented with his Military Medal at Government House in Melbourne in 1920. Following the award presentation, he became the victim of a heartless crime. The Argus newspaper reported:

“Having been presented on Saturday the Military Medal … Raymond C. Runga, of Ouyen, a private in the 6th Battalion, was passing it round for inspection later in the day among a group of four or five men in Swanston Street near Flinders Street. The medal was not returned to its owner, to whom all the other men, with the exception of one, were strangers. The aid of detectives has been sought.”

It is not known if Charlie ever recovered his lost medal.

After researching the history of Charlie, Arthur, and Samson, Jeannie realised the postcards were historically significant.

“I reconsidered my earlier idea of finding a family member to send the postcards to,” Jeannie said. “I now believed the best place for them to be held was in the collection of the Australian War Memorial in Canberra.”

Jeannie Lister contacted Garth O’Connell, a curator at the Australian War Memorial, and asked about donating the postcards to the Memorial.

“We have other embroidered postcards in our collection,” said Garth. “But this is the first time postcards from Indigenous servicemen from the First World War have been donated to the Memorial.”

The postcards were accepted into the Memorial’s official collection. Australian War Memorial Director Matt Anderson said, “Their unexpected recovery is a significant contribution for which the Memorial is grateful.”

“They are an important addition to our collection,” said Garth O’Connell. “They provide a rare insight into the lives of Indigenous servicemen and their families.”

Both Charlie and Arthur are known to have lived into the 1950’s. Charlie devoted himself to religious life, becoming a church deacon. He built and maintained churches in towns across New South Wales before passing away in Leeton NSW on 21 March 1956, aged 66.

How the postcards came to be for sale at a Bendigo market remains unknown.

“The stall holder said that he had purchased them from a country market in Talbot, Victoria,” said Jeannie Lister. “The full journey of these postcards over the past almost 110 years can only be guessed at.”