'He always said that the Bible in his pocket was the thing that saved him'

Warning: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, please be advised the following article contains names and images of deceased people.

Alfred Dow was one of 50 "Black Rats of Tobruk". Photo: Courtesy the Dow family

When Alfred Dow was hit by shrapnel during the Siege of Tobruk, a small pocket-sized copy of the New Testament saved his life.

More than 80 years later, it remains a treasured family possession.

For Alfred’s son, Bob, it’s a poignant reminder of his father’s service during the Second World War.

“He was a faithful gospel preacher and a proud family man,” Bob said.

“He was shot in the leg and hit in the chest, near the heart, with a piece of shrapnel, while serving as a Rat of Tobruk.

“The thing that saved his life was that he had a copy of the New Testament in his shirt pocket.

“Otherwise he would have died.

“It’s just a little New Testament, one that slips in your top pocket ...

“And he’s written a note and sent it back to his sister Grace for safe keeping ... just in case he didn’t make it back.”

Alfred's copy of the New Testament. Photos: Courtesy the Dow family

Alfred Dow is one of more than 50 “Black Rats of Tobruk” who have been identified by researchers at the Australian War Memorial.

Between April and August 1941 around 14,000 Australian soldiers were besieged in Tobruk – a port city vital Allies' defence of Egypt and the Suez Canal – by a German–Italian army commanded by General Erwin Rommel. Subject to repeated ground assaults and almost constant shelling and bombing, the tenacious defenders were derided by Nazi propagandist Lord Haw Haw as “rats”, a term ironically embraced by the Australians.

A proud Aboriginal Elder of the Butchulla people, and a custom chief of North Ambrym in Vanuatu (New Hebrides), Alfred was one of more than 2,000 Indigenous Australians who served during the Second World War.

Alfred Robert Dow was born in Childers, Queensland, on 20 February 1906, the son of Robert Dow and his wife Susie.

Alfred’s father Robert was the eldest son of a custom chief from the island of Ambrym in Vanuatu. He was kidnapped by “blackbirders” as a young boy and brought to Australia to work as an indentured labourer on sugar plantations in northern Queensland.

“Blackbirding” was the 19th and early 20th century practice of enslaving South Pacific islanders, often by force or deception, to work on sugar plantations or cattle stations or as servants in town. The kidnapped islanders were collectively known as “Kanakas”. In Australia, the term is now avoided outside its historical context, as it has been used as an offensive term.

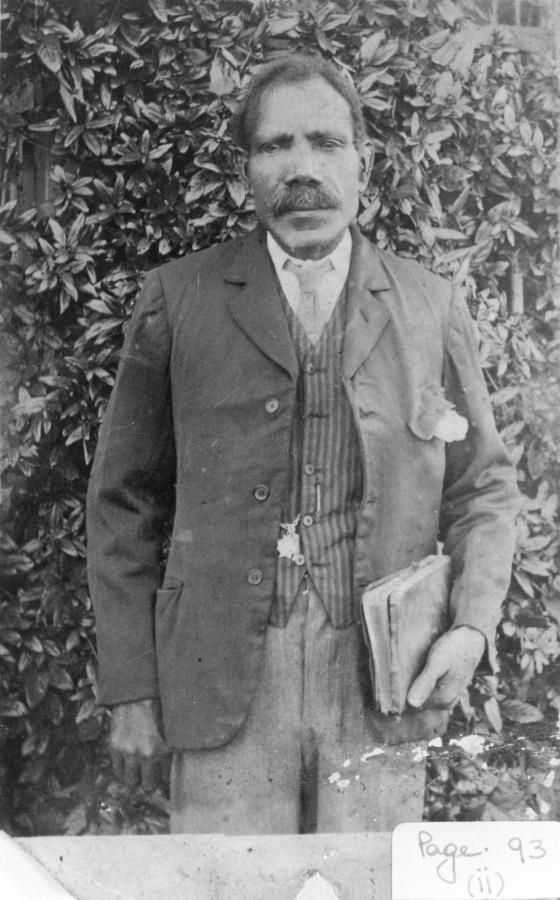

Alfred's father Robert Dow. Photo: Courtesy State Library of Queensland

Considered too young to work in the cane fields, Robert became a house-boy to a Mrs Gibson. He was given the Christian name Robert, and the surname Dow. He was also introduced to Christianity and taught the Bible before being baptised by the Churches of Christ Kanaka Mission at Bundaberg and working alongside the white missionary John Thompson at Childers. Robert couldn’t read or write, but preached the Gospel faithfully, always with a Bible in his hands.

Alfred’s sister, Grace, recalled sitting on her father’s knee during a thunderstorm while Alfred sang the hymn Jesus loves me. Mrs Gibson had taught them the song.

Their maternal grandmother, Mary Ann Dalungdalee, was a Dalungbara woman, who was born at Woongoolba Creek on K’gari (Fraser Island). She was married to John Rooney, an Irishman who had migrated to Australia with his brother Jacob in 1863. The brothers had successfully tendered to build the island’s Sandy Cape Light House, which was completed in 1869 with the help of local Aboriginal people. Mary Ann and John married that same year. Their wedding was reported as being in the Indigenous tradition, with John “exchanging the customary gifts with the elders”.

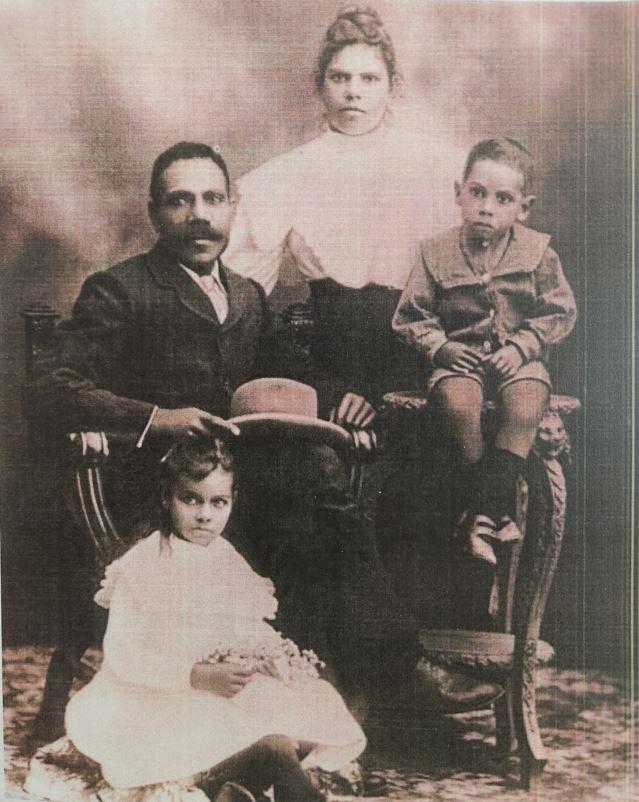

Robert Dow and his wife Susie, pictured with Grace and Alfred. Photo: Courtesy the Dow family

Their daughter, Susie, was Alfred’s mother. She married Alfred’s father Robert in 1905, after the Aboriginal Protector signed a special permit allowing them to marry.

Alfred, the eldest son, left the family home at Pialba in the late 1920s and early 1930s with his younger brother Daniel to study at Glen Iris Bible College in Melbourne. He was appointed as a missionary to the New Hebrides (Vanuatu) by the Church of Christ Overseas Mission Board in 1936 and visited his father’s home island of Ambrym.

“He went to preach over there, but he was never allowed to go to his own village [of Batrarao],” Bob said.

“Vanuatu was run by the British and the French, and he wanted to go back, but the French wouldn’t let him, so he never got to go back to his own village.

“He could only get to a place called Pentecost which is across the water on the next island. Then when the war broke out, he returned to Australia to join the Army.”

Alfred Dow in the dark suit with Mrs Hutton, a missionary, pictured to the left in front of him. Alfred held a church gathering for the Islander people. Photo: Courtesy the Dow family

Alfred and his sister Grace. Alfred left to go to Melbourne to preachers' college. Photo: Courtesy the Dow family

When the war broke out, Alfred was preaching and working as a labourer. He enlisted in May 1940 in Sydney at the age of 34. He went on to serve with the 2/1st Pioneer Battalion in North Africa and the Middle East, and later served as a cook after being shot in the leg and hit by shrapnel.

He was discharged from the army in July 1945. He was one of only two Indigenous Australians known to have been granted land under the War Service Land Settlement Act of 1941, allocated land at Gumly Gumly, near Wagga Wagga, in regional New South Wales, for “dairying and market gardening” in July 1945. His family still holds the certificate granting him the land.

Alfred married Frances Mary Martin in October 1945. They met through a mutual friend in Melbourne and went on to have five children – Carolyn, Susanne, Robert (Bob), David and Philip. Bob was named after his grandfather Robert and is now a custom chief of North Ambrym.

“My mother was white,” Bob said. “And she served in the army as well during the war. She came from a wealthy family down in Apollo Bay, down in Victoria, but because she married a black fella, they disowned her.”

Alfred Dow was a respected preacher and family man. Photo: Courtesy the Dow family

Alfred continued to preach after the war and was actively involved in helping Aboriginal people.

Bob has fond memories of his father sitting with his friend, the prominent Aboriginal sportsman, pastor and activist, Sir Doug Nicholls, the first Indigenous Australian to be knighted and the first to be appointed to a vice-regal office, when he became governor of South Australia in 1976.

“Before the war, he attended Glen Iris Bible College in Melbourne with Sir Pastor Doug Nicholls,” Bob said.

“He and Sir Doug were good mates, and they used to talk about Aboriginal projects and how they could help Aboriginal people.

“At that time, Sir Nicholls was establishing the Aboriginal Advancement League [in] ... Victoria.

“And they spent many hours discussing the future of Aboriginal people in our home.”

Alfred returned to preaching after the war and was an advocate for Aboriginal people. Photo: Courtesy Alfred Dow

The family left the property at Gumly Gumly and moved to Queensland in the 1950s where Alfred continued to advocate for Aboriginal people and projects.

“He probably would have kept going there at Gumly Gumly, but my sister was sick with asthma. The doctor said you either bury her, or you move away, and so that was why we left.”

They eventually relocated to Victoria, hoping to reconcile with Frances’s family. But it never happened.

Alfred died at the Heidelberg Repatriation Hospital in Melbourne on 27 October 1970. His friend Sir Doug Nichols conducted the funeral service. His wife Frances died in October 2015.

Alfred, second from right, with his wife Frances and their five children - Philip, Carolyn, Bob, Suzanne, and David. Photo: Courtesy the Dow family

Like many veterans, Alfred rarely spoke to his family about the war.

“He probably spoke more to my sister about it,” Bob said.

“But the only thing he said to her was that they went across there on the Queen Mary, and the sea was that rough that the propeller on the ship would come out of the water, and vibrate like anything through the whole ship.

“And from what I understand, when he was shot in the leg, he was taken away from Tobruk in a submarine, but I haven’t got any confirmation of that.

“The thing that really puzzles me though is that he was court martialled twice for striking an officer, and was found not guilty on both counts, after representing himself.

“Was it because he felt they were racist? Or was it something else, like his religion? I just don’t know.

“But to be court martialled twice, found innocent twice, after representing himself ... there must have been more to it than what we know at this time.

“If he was such a pain in the neck and such a problem child why did they keep him over there, why didn’t they send him back?”

One of Alfred's photos from his time during the war. Photo: Courtesy the Dow family

Alfred never got to march on Anzac Day or go to an RSL.

“He was a paid up member of the RSL,” Bob said. “But he wasn’t allowed in because he was a black fella. And that’s the way it was for all Aboriginal people back then ... Even though they went to war, they weren’t allowed to drink, and they were separated from the white fellas. He had the RSL badge, and he held that in great respect, but he was not allowed into the clubs because he was Aboriginal and he didn’t attend any of the Anzac Day marches either.”

When Bob wanted to join the army, his father refused.

“I wanted to join the army, but my father wouldn’t let me,” Bob said. “Because I was 17, he had to sign the papers, but he wouldn’t sign the papers for me to join the army. He said he’d sign the papers for me to join the air force, and so that’s why I ended up in the air force.”

Some of the objects Alfred had with him during the war. Photo: Courtesy the Dow family

Today, Alfred’s family still treasure the copy of the New Testament that saved him in Tobruk.

“He was a very proud man, a keen fisherman, and a keen farmer,” Bob said.

“When we lived in Queensland, he used to grow beans and peas and lots of other vegetables.

“He was a very generous person, always willing to help anybody, and always keen to work, even though he had heart problems.

“There were a lot of nightmares... and a lot of screaming at night, so I would say there was also a lot of trauma there ... They used to call it shell shock. Now they call it PTSD.

“But his main passion of course was preaching.

“He always said that the Bible in his pocket was the thing that saved him.”

Michael Bell is the Indigenous Liaison Officer at the Memorial. A proud Ngunnawal/Gomeroi man, he is working to identify and research the extent of the contribution and service of people of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent who have served, who are currently serving, or who have any military experience and/or have contributed to the war effort. He is interested in further details of the military history of all of these people and their families. He can be contacted via Michael.Bell@awm.gov.au