Recent acquisition: new Private Records relating to ‘G for George’

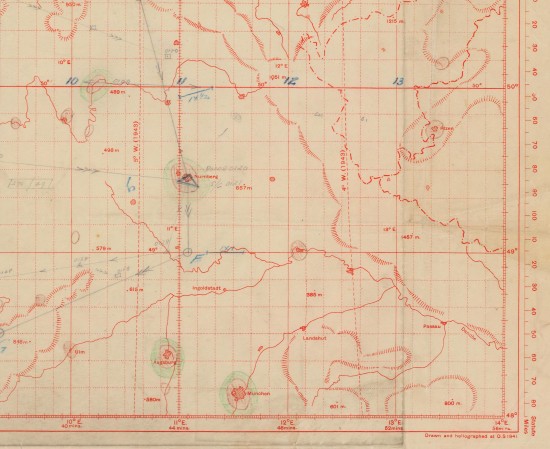

Detail of navigation map kept by William Gourlay, showing Nuremberg

The Australian War Memorial has recently received important documents relating to the Nuremberg bombing raid of 30-31 March 1944 and the iconic Lancaster bomber ‘G for George’. Through a generous donation, the navigation log and map made by William Albert Gourlay, navigator on board ‘G for George’ for the fateful raid, have been added to the Private Records collection (PR04522). These will complement our holdings relating to Bomber Command, and the Nuremberg raid in particular.

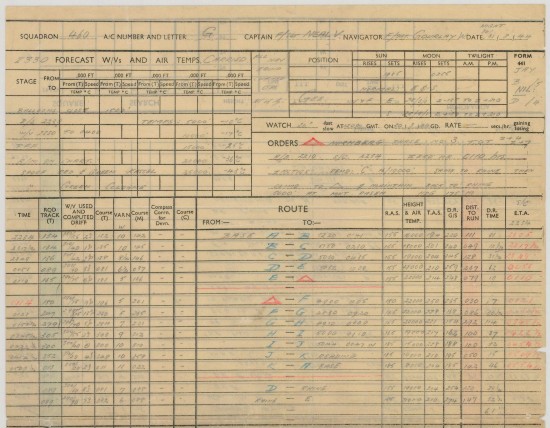

Detail from the navigation log of William Gourlay

A massive bombing raid was planned for Nuremberg on the night of 30-31 March 1944. Nuremberg was a strategic and symbolic target, being both the symbolic heart of Nazism and a major centre of war production. It was also part of the long ‘Battle of Berlin’, the months of bombings devised and ordered by the Commander of Bomber Command, Air Chief Marshal Arthur Harris, intended to crush the morale of German civilians and deliver a fundamental blow to the fighting capacity of Germany.

William Gourlay was a member of 460 Squadron Royal Australian Air Force at the time, and had only recently joined it in February 1944. But for the failure of another Lancaster bomber, Gourlay and his fellow aircrew would never have flown in ‘George’. During their preparation at RAF Base Binbrook, their designated Lancaster was found to be unserviceable, and so, after a race with another aircrew whose bomber was also unserviceable, Gourlay, under the pilot Flight Sergeant Vic Neal, was fortunate to fly in the renowned ‘G for George’.

In his memoir, Gourlay described the task and experience of a navigator: ‘In a small cubicle separated from the pilot’s cockpit by a black curtain, the navigator worked continuously throughout the trip, calculating and checking all the time, it being essential that both log and chart were properly kept up to the minute. The pilot was always advised of all turning times and the new course to be flown, and he would often ask—“Pilot to Navigator, how long to E.T.A.?”’

The Nuremberg raid was problematic from the outset, principally because the raid would occur in full moonlight, and its flight time was over seven hours. When the raid began, problems escalated when there was no cloud cover to protect the bombers.

Like other bombing raids, the raid on Nuremberg assembled a significant complement of bombers: 795 aircraft were despatched, including 572 Lancasters, 214 Halifaxes and 9 Mosquitos. The bombers met resistance at the Belgian border from German fighters. In total, 95 bombers were lost, making it the largest Bomber Command loss of the Second World War. Reconnaissance following the raid found that the mission had in fact been a failure: little damage was caused to the city of Nuremberg, and most of the bombing occurred, incorrectly, at Schweinfurt, 50 miles to the north-west of Nuremberg, and even there the bombing caused little damage.

Reflecting on the Nuremberg raid, Gourlay thought it was ‘grim, enemy fighters really got onto us, and all along the route there were blazing four engined bombers falling out of the sky.’ Unlike so many other airmen, Gourlay was lucky enough to return to base, having seen so many others downed by the German fighters. In September 1944, Gourlay was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for his continued excellent service.