Remembering Athol Adams

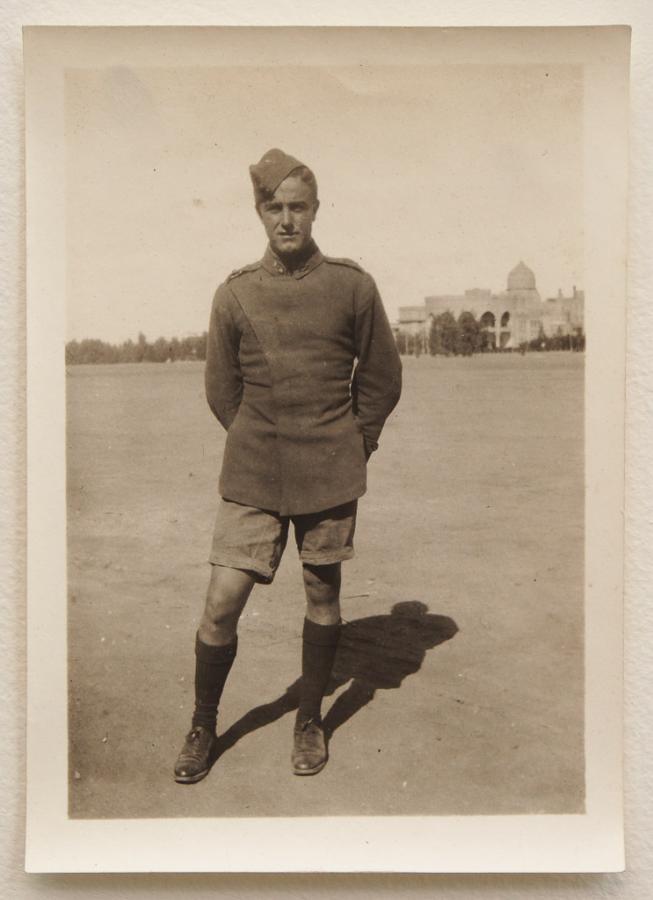

Athol Adams.

Photo: Courtesy Sarah Renwick

Athol Adams was shot four times in the first ten days of the Gallipoli campaign.

“All the wounds have healed up wonderfully,” he assured his mother in May 1915. “And I'll be as good as ever in a few days.”

The 20 year old had enlisted in August 1914 and would often write to his mother, Adah, in Melbourne.

With one son already away at war, and another determined to go, she was busy doing everything she could to aid the war effort, and would treasure Athol’s letters.

He never told her about the horrors of war, or the fears that he had, but wrote of his everyday life as a soldier.

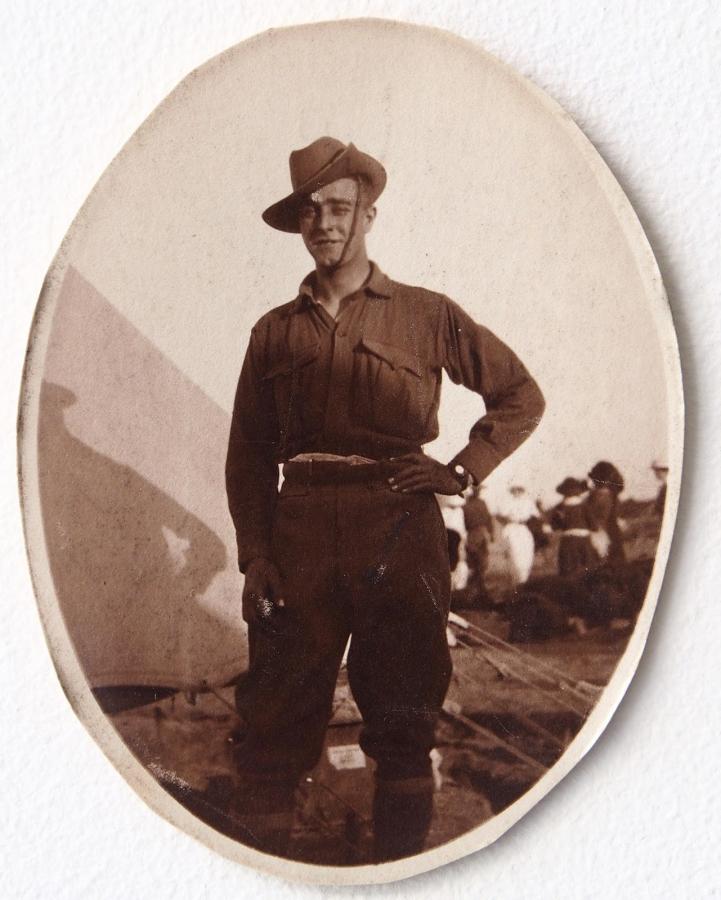

Athol Adams.

Photo: Courtesy Sarah Renwick

To Athol’s great-niece, Sarah Renwick, the letters are particularly special, their simplicity making them all the more moving.

“They’re just day-to-day things,” Sarah said. “It’s just a young man writing home saying, ‘We did this today.’”

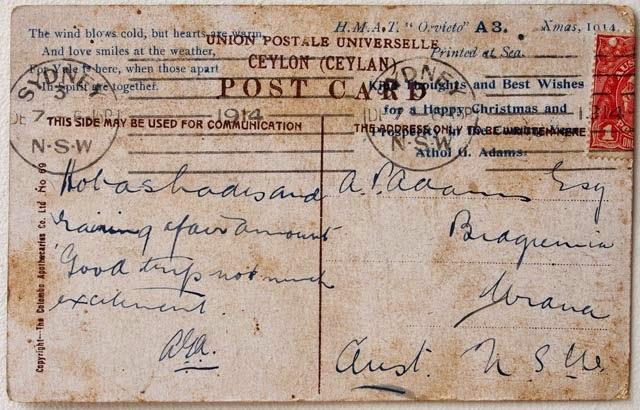

One hundred years after they were written, Sarah began publishing Athol’s letters online, along with photographs, postcards, and biographies of members of the family. She created a blog, Not Mentioned in Dispatches, and conducted research at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra to learn more.

“I was left some material when my late father died – literally in a trunk in a garage – and that chest of materials was from my father’s two uncles who both served in the Great War,” she said.

“There were letters, medals, badges, uniforms, buttons, all sorts of things, and I was conscious of … being the sole owner.”

A postcard from Athol Adams: "Hot as Hades and raining a fair amount. Good trip not much excitement.".

Photo: Courtesy Sarah Renwick

She painstakingly photographed Athol’s letters and posted them online so that family members could read his story in his own handwriting.

“I wanted to get a sense of the unfolding story,” she said.

“They were just letters wrapped up in pink ribbon, but no one else was going to have a look at them … so I was interested in trying to preserve the history.

“He was an average soldier, so there’s no great import – nothing too important historically – but if everyone writes these together it is important because it builds a collective picture that allows the minutiae to tell their own story.”

Her great-uncle, Athol Gladwyn Adams, was born in 1894 in South Yarra, Melbourne, the youngest of four boys. He was working as a clerk in the family shipping company when he enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force just a few weeks after war was declared.

“I think he saw this as an adventure and an opportunity, so he signed up,” Sarah said. “They felt they were part of the Empire, and they wanted to do something. They wanted to be a part of this enormous enterprise, and they wanted people to proud of them.”

Sergeant Athol G. Adams is pictured third from left in the back row wearing his slouch hat.

Photo: Courtesy Sarah Renwick

Athol served with the 5th Battalion and was part of the second wave of troops to land on Gallipoli on 25 April 1915. He was shot through the upper arm soon after getting ashore, was wounded again just 30 minutes later. A bullet hit his wrist, smashing his watch, and putting his left hand out of action.

“I just don’t think we can imagine the shock of that day,” Sarah said. “He was in one of the later waves to hit the beach and, of course, by then it was daylight …

“The Turks already knew where to aim by then, and he was shot twice at the landing. He was put onto one of those barges, onto the hospital ship, patched up, and sent back to Anzac Cove ten days later where the 5th Battalion was being pulled out of the trenches.

“He met up with them on the beach and they were put onto barges and sent down [to Cape Helles at] the bottom of the peninsula to take part in the allied push north, and then he was injured twice in the battle of Krithia; a very unheralded part of the conflict.

“It was shockingly hideous because it was all flat country covered in herb and scrub and low bush, so there was no cover.”

Athol Adams in his Australian Flying Corps uniform with Observer's badge.

Photo: Courtesy Sarah Renwick

The disastrous attack resulted in many casualties, including Athol.

“I got hit again,” Athol wrote. “This time in the right thigh, a clean hit right through. I couldn’t walk and while I was being taken back I got another in the right lower arm. The bullet hit a man who was helping me and broke his arm and then went into me and stayed in my wrist.

“Am quite alright. They took the bullet out under gas. I'll send it out and I think you had better give it to Bill [the family’s nickname for his eldest brother, Arthur] to go on his watch chain with that bit of his knee.

“I previously sent my wrist watch [which was smashed during the Gallipoli landings] and a Turkish bullet which was in my haversack. I hope you get them alright.”

Athol went on to take part in the battle of Lone Pine, was seconded to the Imperial Camel Corps in Egypt, and later transferred to the Australian Flying Corps, qualifying as an observer.

He was training to become a pilot, and had passed his exams, when, in February 1917, he was severely wounded in an aeroplane accident. He was admitted to the hospital in Alexandria, but died soon after.

Athol's grave.

Photo: Courtesy Sarah Renwick

When his mother received the news, she is said to have smashed every piece of her collection of German Meissen porcelain, including an entire dinner service.

But there was more grief to come. In May that year, Athol’s elder brother, Valentine Harold Adams was killed while serving on the Western Front with the Royal Flying Corps. He’d been born on Valentine’s Day in 1892 and had paid his own way to England to become a pilot during the war.

Their mother was left heartbroken. She kept Athol’s letters in a trunk, which she passed on to her only surviving son, Sarah’s grandfather, Arthur Parker Adams, who found them too painful to look at.

“The family was shattered by the tragedy of the loss of the two boys only three months apart,” Sarah said.

“Their father had died when they were all very young – Athol had not even been born – and the brother who was older than them died … just after he left school so my grandfather lost three brothers as 19, 22, and 24 year olds.

“It was too much sadness, and I think that was probably quite common in World War One. It was shockingly bad … and there were a whole lot of things people couldn’t talk about.”

Athol's mother Adah Sherwood was devastated by the loss. This portrait of her was among Athol's personal effects which were sent home to Australia after his death.

Photo: Courtesy Sarah Renwick

Her grandfather kept the trunk and passed it on to his son, Sarah’s father, Harold Adams.

“My grandfather … lost his wife quite young [and] was quite a reclusive man, so there was a lot of family stories [about them], but very nebulous,” she said. “We knew the two great uncles went off to war and died … but we didn’t really know terribly much else.”

Athol was buried at the Hadra War Memorial Cemetery in Alexandria the day after he died, but for nearly a century, no one from the family visited Athol's grave. Like many of the families whose loved ones were killed in the First World War, their grief was compounded by the fact their graves were so far from home. Athol's mother, Adah, did not get to travel to Egypt to see her son's grave, nor did his step-father, Guy Sherwood, or his beloved aunts, “May” and “Puff”, or his brother, Arthur, the last of the four Adams boys.

It was not until 2006 that members of the family could finally made the pilgrimage to Alexandria to visit the grave. Sarah went with her father, Harold Adams, the youngest of Arthur's children, who had served with the Royal Australian Navy from 1946 until 1983.

“We all got dressed up in our finest, Dad put his tie on, and off we went to the cemetery,” Sarah said. “It was a very moving moment … and Dad gave the gardeners Australian War Memorial badges.”

Athol Adams and his elder brother Valentine. The frames clip together and are held on a golden bracelet worn like a wristwatch. It is understood that this was commissioned by the boys' mother, A.E Sherwood, after their death and worn by her.

Photo: Courtesy Sarah Renwick

For Sarah, it was a fitting tribute to a man she had come to know through his letters and postcards.

“You do feel like you get to know him,” she said. “But it’s a bit like a foggy picture.”

She said the Memorial had been invaluable in helping her learn more about her great uncle and what he went through. She spent hours trawling the Memorial’s collection of photographs online and studying unit war diaries.

“It’s been incredibly valuable in all sorts of ways,” Sarah said. “I think as Australians we’re interested in a people history – we’re not just interested in generals, and dates, and maps – so it’s been immensely important.

“It fills in a lot of the gaps, and … adds so much more to the picture… Athol would mention some of the other soldiers in his letters, and I could try and find out where they were, and where they ended up, and then find photos of them. And you find all that at the War Memorial.”

She hopes by publishing Athol’s letters online, her blog will help ensure their story lives on.

“I think it’s a nice way to keep these stories carrying down the generations,” she said. “I come from a family who has had generation upon generation involved in the military… so yes … it’s important.”

Her great-uncle’s story was also told at a Last Post Ceremony at the Memorial, where Sarah and her family laid wreaths that she had made out of rosemary in memory of Athol and his brother Valentine.

“We always go to the War Memorial,” she said. “It’s an incredibly moving place, and it tells our story.”