'Guess you will be thinking I’ve gone up in smoke'

Kathleen Neuss: "She was just a lovely fun-loving lady." Photo courtesy: Michael Noyce

When Australian Army nurse Kathleen Neuss sat down to write a letter home from Singapore on 6 February 1942 she couldn’t have known it would be her last. “Guess you will be thinking I’ve gone up in smoke,” she quipped. “There is plenty of it about.”

Ten days later she was dead, one of 22 Australian nurses who were ordered into the sea at Radji Beach and shot by Japanese soldiers during the infamous Banka Island massacre.

Her life was commemorated in a Last Post Ceremony at the Australian War Memorial, at which her family and friends laid wreaths in memory of those who were killed.

More than 60 years after her death, Michael Noyce found Kath’s final letter among his parents’ belongings. His father, William, was Kath’s younger brother, and his mother Philippa was her best friend.

“When my parents died, I found 20 odd letters in a little leather satchel,” he said. “It was like Kath was there. It brought Kath alive.”

Sister Kath Neuss entertaining a child at Royal Prince Albert Hospital, Sydney.

Noyce never met his aunt, but he had grown up hearing her story. “As long as I can remember it was always Kath,” he said. “She was never there in body, but she was always there in spirit, and her presence was always very strongly felt …

“Reading and transcribing her letters … she became a real person. You knew her. You knew what her emotions were. You knew what she was thinking. You knew what she liked. You got to know her as a human being. You got to know her as if you were talking to her...

“She was just a lovely fun-loving lady. She was a tall, fun loving and gregarious woman with brown eyes and dark hair. She had a wicked sense of humour and was full of life, her letters home telling of young woman enjoying her experiences overseas …

“She nursed with my mother at Royal Prince Alfred in Sydney and they were best friends. Kath was a year or so older than my mother and … in October 1940 Kath’s younger brother – my father – went to say goodbye to his sister before he embarked on the Queen Mary for the Middle East.

“My aunt and my mother were living together in an apartment in Darlinghurst in Sydney, but he got his day or the hours mixed up and Kath was on duty nursing and mum was at the house. My parents met for 36 hours there and then he went away for two and a half years. He came back and they were married four and a half days later … [so] I wouldn’t exist if my father hadn’t mixed up the times to say goodbye to his older sister.

“She was very close with my father, even though they were five or six years apart … My father kept a diary leading up until the siege of Tobruk which he gave to me not long before he died. We didn’t even know it existed, and the diary was given to him by Kath. On the back it’s got, ‘Finish this Willy and I’ll give you another one for next year.’ But she was killed in the meantime.”

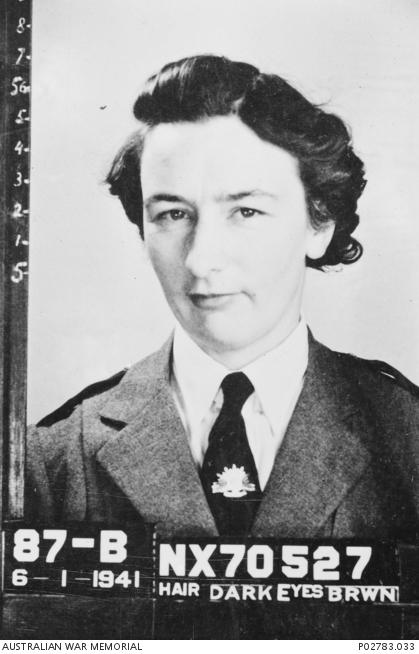

Sister Kath Neuss's enlistment photo.

Neuss enlisted in the Australian Army Nursing Service in December 1940 and embarked for Singapore in February 1941 on the SS Queen Mary, the same ship her younger brother William had sailed on only a few months earlier.

She was working on the Malay Peninsula when the Japanese attacked the US naval base at Pearl Harbor in December 1941 and invaded Malaya. Once the fall of Singapore became inevitable, Neuss was one of 65 Australian nurses who were evacuated. Although they protested leaving their patients, the nurses left Singapore on 12 February aboard SS Vyner Brooke. Two days later, the desperately overcrowded ship was attacked and bombed by the Japanese, sinking in the Banka Straits within half an hour of Sumatra.

Neuss was hit in the hip by shrapnel from a bomb blast, and had to be helped up on deck by her friends Wilma Oram and Mona Wilton, who were already wounded. They all but carried her to a lifeboat, her friend Pat Gunther giving her tin hat to Neuss in case she needed to bail water from the lifeboat, saying, ‘We’ll see you on shore’. Neuss gave Gunther her lifejacket, and Gunther made it to another part of Banka Island and survived the war as a prisoner of the Japanese.

Many lives were lost during the sinking. Some, like Neuss, were helped into lifeboats, while others swam or desperately clung to debris. Those who could made for the nearby Banka Island. It was there that some of the survivors travelled from Radji beach to the nearest port to formally surrender to the Japanese, but Neuss was among the 22 Australian nurses who remained to tend the wounded.

When the Japanese arrived at the beach on the morning of 16 February, the men were marched around the rocky headland and executed. After returning and wiping their bayonets in front of the nurses, the Japanese turned their attention to them.

The Japanese signed for the remaining nurses and one civilian woman to march into the sea. Aware of what was about to happen to them as they walked to the water’s edge, Matron Irene Drummond said to her sisters, “Chins up, girls. I’m proud of you … I love you all.”

When the water reached their waists the Japanese opened fire with machine-guns. Of the 22 Australian nurses ordered into the sea that day, all but one were killed. The only nurse to survive the massacre was Sister Vivian Bullwinkel who was shot in the hip but survived by feigning death in the surf. After the war she contacted the families of the nurses who were killed and testified at the International War Crimes Tribunal.

Vivian Bullwinkel was shot in the hip but survived by feigning death in the surf.

Noyce said his family were devastated when they finally learned of his aunt’s death.

“It basically killed my grandparents,” Noyce said. “They died in 1950, 1951, and they were both only in their 60s and 70s, but it basically shattered them.

“My father had gone through the war and had seen a lot of his close mates killed so he was somewhat conditioned to tragedy – and close tragedy – but it certainly did have a big impact on them …

“My father was one of 13 friends and acquaintances, including Kath, who all joined up for the Second World War … and he was the only one of the 13 who survived the war.”

Noyce has since been to Banka Island three times to pay his respects to those who were killed. He first went to Banka Island with his cousin Ian three years ago and returned on the 75th anniversary of the massacre with a 20 kilogram bronze plaque dedicated to those who were executed on Radji beach. He hopes the story of those who were killed will never be forgotten.

“To imagine what happened there 75 years ago was quite chilling I tell you,” he said. “[But] the more the stories of all these people can be told the better we all are.”