Remembering the Callaghan brothers

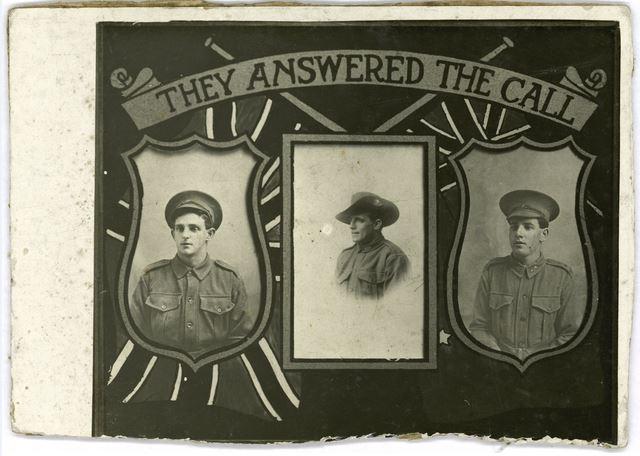

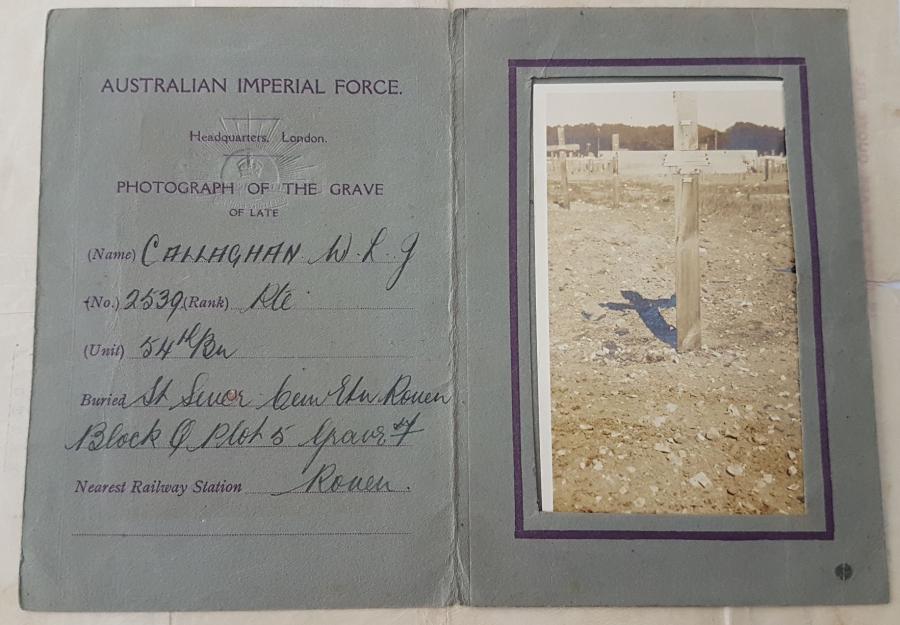

Studio portrait of Private Walter Leslie James Callaghan, 54th Battalion. He died of wounds on 4 September 1918.

Walter Callaghan was one of three brothers killed on the Western Front during the First World War.

His mother Mary was invited to unveil the Lithgow Soldier’s Memorial in recognition of the loss of her three sons, but nothing could ease her pain.

Just a few days before Walter left Australia, word had come through that his younger brother Horace had been killed in France.

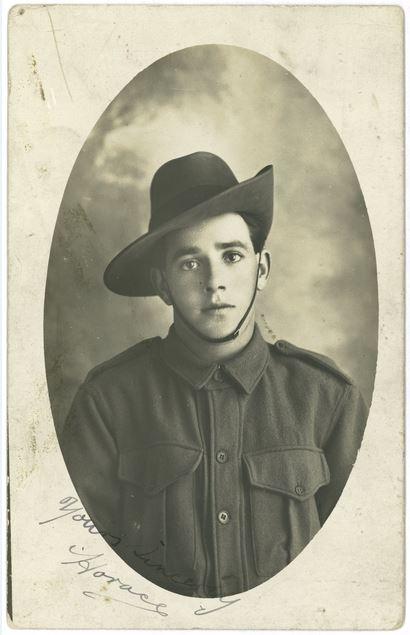

Studio portrait of Private Horace William James Callaghan, 9th Battalion. He was killed in action on 23 July 1916.

His other younger brother, Stanley, was still serving, and his mother made him promise that he would not play in the local football team’s final game out of respect for his brothers and their loss.

When their team started losing, Walter ran on to the field, rolling down his putties as he went. He scored the winning tries, much to the delight of his mates, but not his mother.

When he sailed for active service a few days later, leaving behind his wife and young daughter, his mother was still angry with him. She would never see him again.

Portrait of Private Stanley Owen James Callaghan, 18th Battalion. He was killed in action on 15 November 1916.

His granddaughter, Jan Heldon, grew up hearing the story from her mother Vera, Walter’s only child, and her grandmother, Essie, Walter’s widow.

“It’s part of my life; it’s part of my family; and it’s part of who I am, so it’s very important to me,” Jan said. “My grandfather was always talked about and I can remember as a child there was a photograph of him still in the house.”

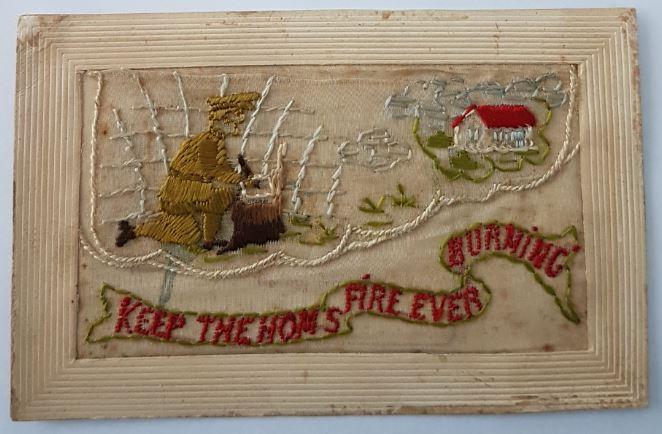

Jan’s mother Vera was only two years old when Walter went away to war and she would often go to sleep at night with his photo. She talked to it as if it was him, and kept the letters and postcards that he sent home for the rest of her life.

Vera with the portrait of her father, Walter. She was only two years old when Walter went away to war and she would often go to sleep at night with his photo. Photos: Courtesy Jan and Ken Heldon

“My mother kept them all,” Jan said. “They were obviously treasured first by my grandmother and then my mother. She had a special box … and they would sit on the top of the wardrobe.

“It’s heartbreaking to read them and to think about what my grandmother and great-grandmother went through.

“He was known to the family as Les, and my brother was named Les after him.”

Studio portraits of brothers Stanley Owen James Callaghan, Walter Leslie James Callaghan, and Horace William James Callaghan who were all killed during the First World War.

When the First World War broke out in 1914, Walter’s younger brother, Horace, was determined to enlist. He first attempted to sign up in their home town of Lithgow, but was rejected because he was only 17 years old. Undaunted, Horace jumped on a horse and travelled north to Queensland where he lied about his age. He successfully enlisted in August 1915 and eventually joined the 9th Australian Infantry Battalion.

His older brothers Stanley and Walter soon followed, Stanley enlisting a few months later in October 1915, Walter in July 1916.

Horace would be killed in his first major battle on the Western Front less than a fortnight after Walter enlisted.

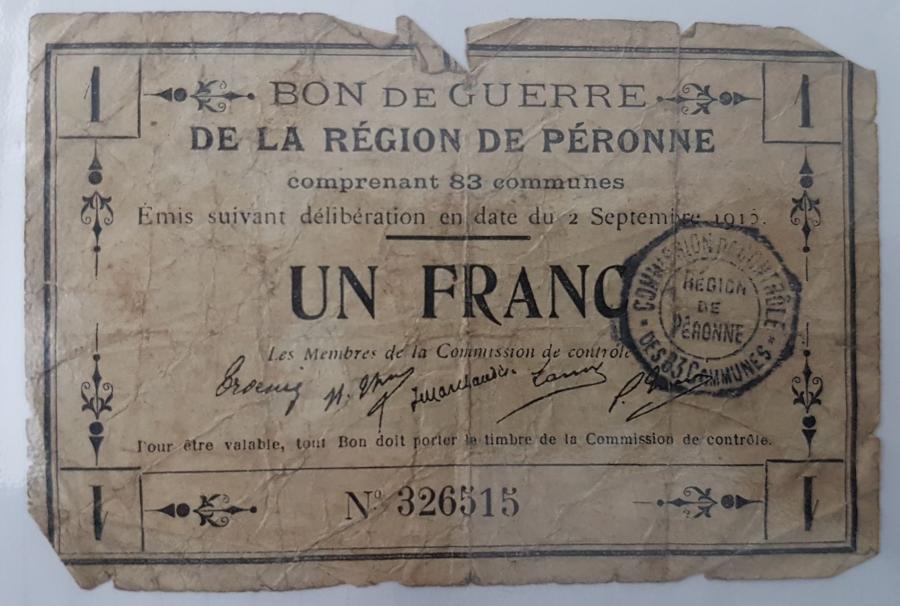

The 9th Battalion had been moved to the front line in July 1916, tasked with holding a sector of the trenches near the town of Pozieres in the Somme valley in France. They attacked the German positions, and assaulted the German trench, but were pushed back in heavy fighting. They then received orders that they were to form part of the 1st Australian Division’s attack on the town of Pozieres.

Horace took part in the first attack that took place just after midnight on 23 July. He ran across no man’s land in the darkness, but when he was about 100 metres from his trench a series of German flares lit up the battlefield. Horace jumped for a nearby shell crater, but was shot as he tried to reach cover.

Stanley learned of his younger brother’s death just weeks before he arrived in France, but there was no time to mourn. Stanley joined the 18th Infantry Battalion in the Ypres sector of Belgium, and immediately faced the horrors and hardships of trench warfare. His unit came under heavy artillery fire the day he arrived, and when it moved to the Somme region of northern France the men endured the seemingly endless rain of October and November, and the mud and cold that came with it.

Stanley was killed not long after. He was camped behind the lines with his unit on 15 November when an errant German shell landed near him, killing him instantly.

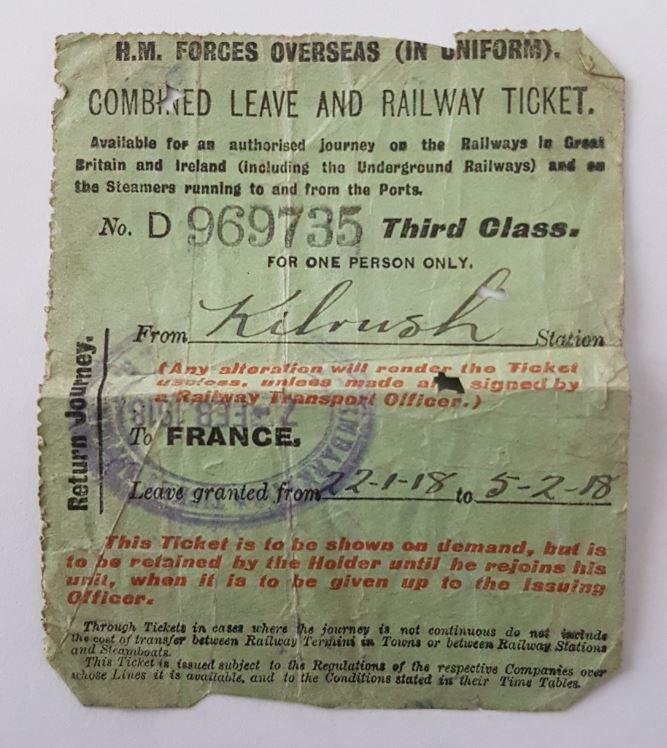

His older brother Walter joined the 54th battalion in the Somme region of northern France not long after in January 1917.

He had lost his two younger brothers within months of each other, and the hardships and horror of trench warfare soon took their toll.

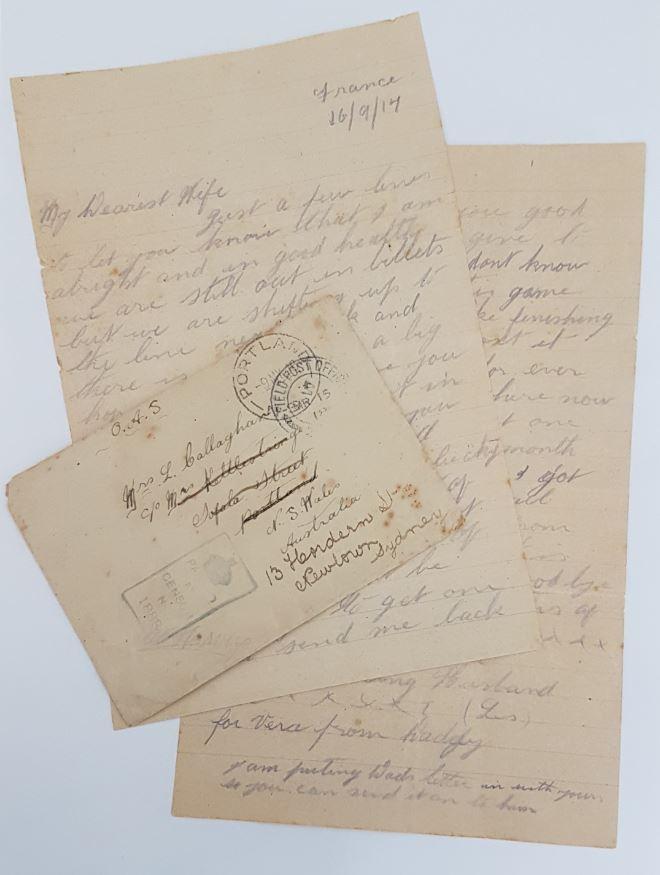

“Well kid,” he wrote to his wife Essie in September 1917. “I don’t know what to make of this game. One week it looks like finishing soon and then the next it looks like going on forever.”

A few days later, he took part in the battle of Polygon Wood in the Ypres region of Belgium. Although Australian troops successfully took their objectives and held off German counter attacks, they suffered more than 5,700 casualties in a single day.

“Just a few lines to let you know that I am still alive and kicking,” Walter wrote in October. “We have just come out of the line again and we had a tough time in there this time, the worst I have had yet, and I don’t want to have another time like it.

“I can tell you there was that much shell fire that it is marvellous that a fly can live in it, let alone a man, but I came through it without a scratch again.

“The winter is just about on us again and I think it is going to be a very cold one … it is that cold now that everyone is near dead with cold.

“There are few that can rise there voice higher than a whisper so God knows what it will be like before the winter is over…”

In late January 1918, Walter’s wife Essie wrote to authorities pleading for him to be allowed to come home. He was having fits, she said, and rapidly losing weight.

“I feel very worried about him,” she wrote. “He lost two brothers in 1916, one in July and one in November: so I really think his mother has done her share for her country and there is no more that can go.”

Despite her pleas, Walter continued to serve at the front. Whenever he could, he sent postcards and letters to his wife and his “darling daughter” Vera, who missed him terribly.

“She went to sleep with your photo last night,” Essie wrote. “She puts you under the blankets alongside of her and covers up all but your head, then she puts her hands together and says God bless my daddy.”

They anxiously awaited his letters and when Walter was wounded in France in April 1918 Essie feared the worst. He was hospitalised with shrapnel wounds to his left hand and evacuated to England to recover after his unit came under heavy German artillery fire while being relieved from the front lines.

Walter was able to rejoin his unit in late August 1918, but his return to the front was brief. On the 1st of September, Walter was wounded in action during the assault on Mont St. Quentin. He and the men of his unit jumped out of their trenches at 5 am and were met by a heavy German bombardment. Walter was badly gassed, and received severe gunshot wounds to the head. Everything was done to try and save him, but he died in hospital on 4 September, only a couple of months before the Armistice was signed on 11 November.

Walter’s family was devastated by the loss, and in October 1918, his mother Mary was asked to unveil the Lithgow Soldiers’ Memorial, a small gesture by the town to acknowledge the sacrifice of her three sons.

Years later, Jan’s husband Ken, a retired army officer and Vietnam veteran, took part in an Anzac Day ceremony at the Lithgow memorial. It was during one of his first postings after graduating from Duntroon, and he was at first unaware of the family connection. He has since spent years researching the lives of Walter and his younger brothers, Stanley and Horace, in a fitting tribute to their service and sacrifice.

On the 101st anniversary of Walter’s death, the family laid wreaths at a Last Post Ceremony commemorating the brothers’ lives at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra.

“I just wish my mother was still alive; it would have meant a lot to her,” Jan said.

“Our sons and our grandchildren will remember it for the rest of their lives; none of them will ever forget it … I’m just sorry I never knew him, but they are remembered.”