Remembering the Colenso brothers

Informal portrait of the Colenso family of Kingsford, NSW. All four brothers, Ray, Frank, Ted and William, enlisted on 1 July 1940 in 2/18 Battalion. They are pictured with their parents, William and Winifred Colenso.

The Colenso family’s lives have been shaped by war. “The whole thing has been etched into our DNA,” said Bill Colenso, whose father was one of four brothers who enlisted together during the Second World War.

“There was a big photo of the four boys above the mantelpiece my whole life, and there were always photos of my dad. It’s been burnt into our brains; we’ve been brought up with it.”

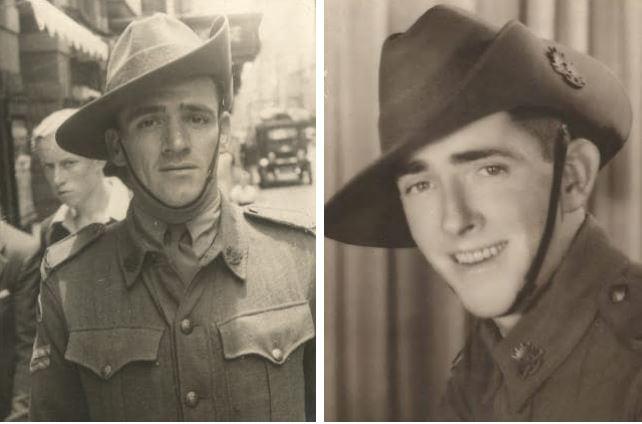

Bill’s father, William (also known as Bill), was the eldest of the four Colenso brothers — William, 30, Frank, 28, Ted, 26, and Ray, 20 — who enlisted together to look after one another.

Bill was born after the brothers sailed for Singapore and never met his father.

His father and Ray were killed within days of one another as Singapore fell to the Japanese. Their stories were told in two Last Post Ceremonies at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra.

Members of the Colenso family at a Last Post Ceremony at the Memorial.

But the Colenso family’s story begins more than two decades earlier with their father William Sr and the outbreak of the First World War. It was a throwaway line overheard by his wife, Winifred, in line at a grocery store in the eastern suburbs of Sydney that led to the family’s involvement in two world wars.

“She heard two ladies talking about how her husband had resigned from the NSW Irish Rifles,” said Bill’s cousin, Dianne Mullin, whose father Frank was the second eldest of the Colenso brothers.

“They said he must have been scared to go to war. She went straight home and told William he had to enlist because she wasn’t going to hear anyone calling her husband a coward.”

William Sr joined the 18th Infantry Battalion in October 1916 and was sent to England where he remained until he was medically discharged in 1918, never seeing active service.

But the family wasn’t spared from tragedy.

Winifred’s brother, William Moloney, was wounded on the Western Front in 1917 and died in a French military hospital.

Her other brother, Edward, returned from the war, but was severely wounded, and remained an invalid for the rest of his life.

So when her 19-year-old son Ray first came to her with enlistment documents during the Second World War, she refused.

“Ray was only 20 when he enlisted,” Dianne said. “He couldn’t go until he was 21 without his parents’ permission, so the brothers decided they wouldn’t go to war until they could all go together, and she said, ‘I’m not signing the papers.’

“They said, ‘It’ll be over by Christmas,’ and she said, ‘I’ve heard that before.’ She’d had one brother killed at Fromelles, and the other one came home gassed and couldn’t breathe properly for the rest of his life.

“But they pestered and pestered and pestered her, and finally, when he turned 20, she let him go, and Ray celebrated his 21st birthday over there.”

The four brothers enlisted together on 15 June 1940 and were assigned consecutive service numbers. Their younger brother, Les, was too young to enlist.

“Ray was the one who wanted to be a soldier,” Bill said. “The others went to look after him; it was one in, all in, as far as enlisting, and they all stuck together. They were like peas in a pod.”

The four Colenso brothers, William, Frank, Ted and Ray, enlisted together and were given consecutive service numbers. Their youngest brother Les was too young to enlist.

The brothers joined the 2/18th Battalion together, following in their father’s footsteps.

On 1 February 1941, they set sail from Sydney Harbour and disembarked at Singapore 17 days later, moving north to spend 1941 training in the steamy tropical conditions of the Malay Peninsula.

Ray would often write poems for other soldiers in exchange for paper, and would write love letters for soldiers to send home to their sweethearts. He wrote the following poem the year before his death:

In dreams I often travel to the land I know so well,

In sleep I find much comfort despite the shot and shell,

Pleasant dream, old cobber, on watch I’ll take my turn,

Though while awake we quell it, our hearts for home do yearn.

Ray would never return to Australia. By the following year, British forces had withdrawn from the Malay Peninsula onto Singapore Island, and on the morning of 8 February 1942, the Japanese launched their attack to take Singapore.

The four Colenso brothers were helping to defend a sector of Singapore’s north-west coast when the outnumbered and overstretched Australians came under an intense mortar and artillery barrage.

“They were holed up in front of the causeway and they were shelled for 24 hours,” Dianne said. “They just had to cop it and then the shelling stopped, and Dad said that the silence and the dark was even more frightening – the shelling had been bad enough, but the silence was awful.”

Concerned, Ray asked his corporal if he could go ahead and see what was happening.

“Uncle Ray came flying back through the bush, and he said, ‘There’s Japanese, 200 yards ahead of us,’” Dianne said. “They said, ‘Spike your guns, and run,’ so they took the firing pins out, threw them into the bush, and Bill said to my dad, ‘Frank, you haven’t got a weapon,’ and he grabbed his bayonet out, and said, ‘Take this, and put it in your belt.’ Dad said, ‘No, no, Bill,’ but he insisted. He said, ‘You need a weapon,’ so Dad shoved it in his belt and ran.

“That was the last time they saw Ray, and I owe my life to him because he actually had the common sense to go and see what was happening; otherwise they all would have been killed.”

Ray wrote poetry instead of letters. He would write love letters for other soldiers to send home to their sweethearts in exchange for paper.

The bombardment had been followed by a major Japanese landing and the Australian forces were completely overrun.

“Dad was running through the rice paddy and the ground went from under him. He said, ‘I was trying to get out and the mud just kept coming … He thought, ‘I’m going to drown; that’s how I’ll finish up; and no one will know where I am,’ and then he remembered the bayonet, and he used the bayonet to cut his way out …

“After the war, Dad worked as the general assistant at a school and that was the story that he always told the kids on Anzac Day; how someone’s kindness saved his life.

“When Dad got back to Singapore, he gave the family whistle, and Bill – big boofy Bill; he was a real man’s man – came racing out, threw his arms around Dad, and kissed him all over,” Dianne said.

“In those days, men didn’t do that, but they thought Dad had gone too. He said, ‘Have you seen the kid?’ When Dad said, ‘No, isn’t he back,’ he said, ‘Ted’s back, but the kid isn’t,’ so Bill signed up to go out and look for him.”

Bill and Ray never made it back. In the initial confusion of the attack and the subsequent loss of Singapore, they were reported as missing together with Frank and Ted, but were later confirmed to have been killed in action, Ray on the 9th of February and Bill two days later.

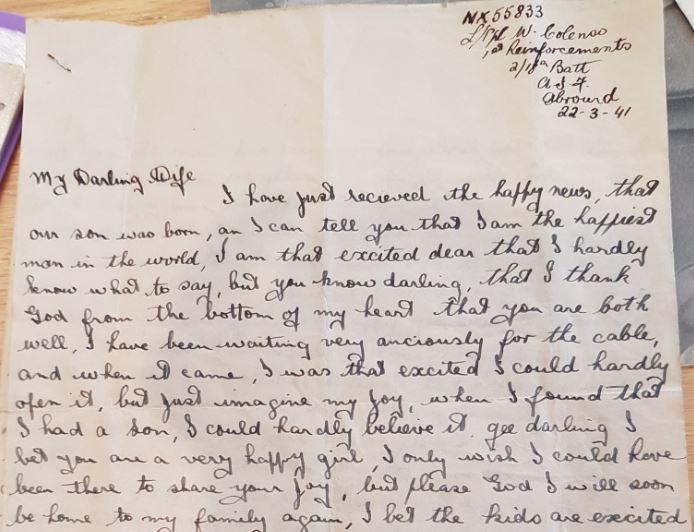

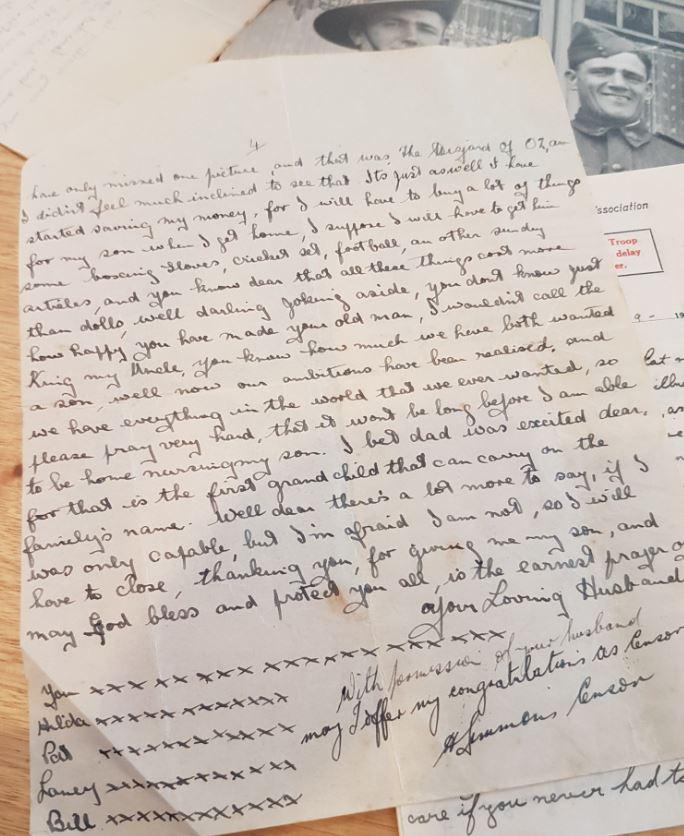

The letter Bill's father wrote to his mother after he was born.

Bill left behind his wife Hilda, and four young children – Hilda, Pat, Elaine, and Bill.

His name is listed on the Singapore Memorial, which commemorates over 24,000 Commonwealth servicemen of the Second World War who have no known grave.

“Ray was buried at Kranji [War Cemetery], but Dad was never found,” Bill said. “Every knock on the door, my mum thought, ‘Well this could be him coming home,’ and for years she half expected that the doorbell would ring and he would walk through the door. And we lived with all that for all our lives. There was no closure.”

Every time the family celebrated a birthday or wedding, Bill’s mother Hilda would add that they had “two up in heaven”.

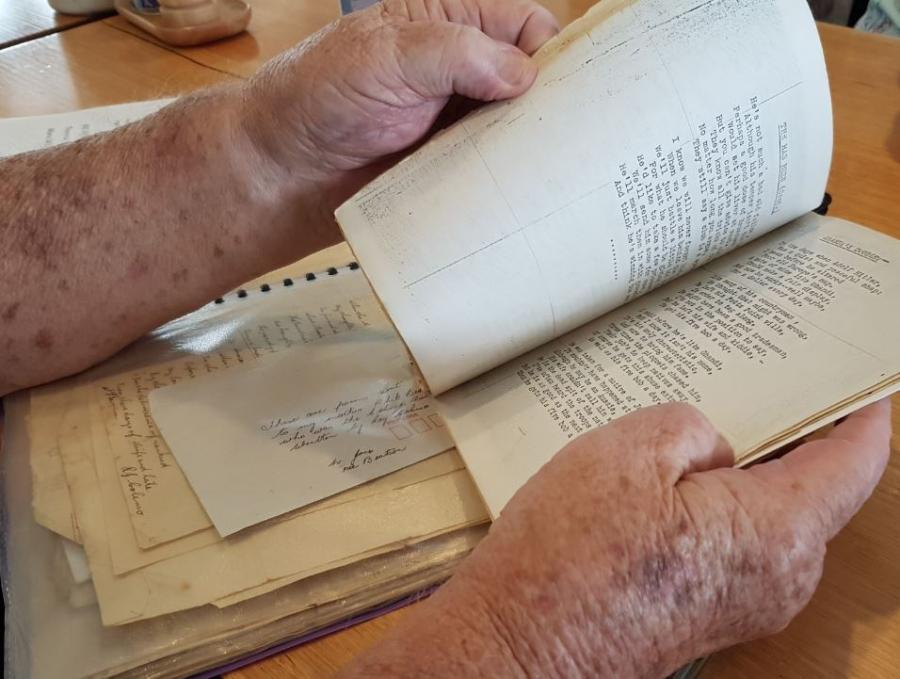

Today, Bill still has the last letter that his father wrote to her, saying, “I can only write four pages today Hilda because Ray’s writing love poems for paper.”

“I’ve even got the envelopes,” Bill said. “She kept them in a box and had them all neatly folded in it.”

Bill's father always signed off his letters in the exact same way.

Bill’s mother never remarried and treasured the letters for the rest of her life.

As the brothers were initially reported missing along with thousands of others, she did not learn of her husband’s fate until after the war when he was declared presumed dead in 1946.

The family’s story was told in an article in The Australian Women’s Weekly in July 1942.

“Yes, the waiting is terrible,” their mother Winifred said. “But I am quite confident my boys are safe and they will be coming back to us. I am sure all the other mothers feel the same.

“My four boys all going away together; it was a terrible blow, but I am so proud of them.”

When the family finally received letters from the two surviving brothers, now prisoners of war, in September 1943, their mother said, “I’m just praying for the next mail about the other two boys. I never gave up hope.”

Ted and Frank had been captured by the Japanese and were now prisoners of war together.

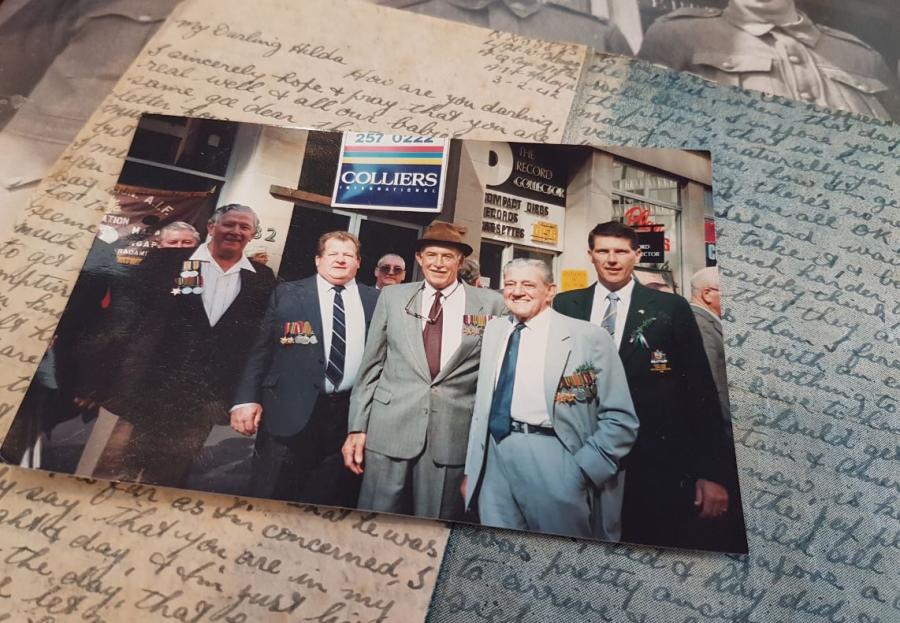

Bill Colenso, second left, marched with his uncles, Les and Frank, on Anzac Day.

“It was horror on horror on horror,” Dianne said. “They used to go out to work every day, and if the Japanese caught you stealing it was head off and on to a stake by the side of the road. They’d pass the rotting heads every day and they weren’t game to look because it might have been the Chinese fellow who had given them food the day before and risked his life at the fence for them…

“Ted got very sick and couldn’t work so Dad persuaded the doctor not to put him on sick call and he volunteered them both for woodcutting so that they would still get rice. Dad was a footballer, so although he wasn’t all that big, he was very strong, and he figured that he could put Uncle Ted in a hole, and he could do twice the work, and the Japanese wouldn’t know; that way Uncle Ted could still get food and no one would have to share.

“When they were sent back, they were sent on the work party to Blakang Mati – the island of the dead – and they were there for nearly two years. When Uncle Ted got sick again, the doctor said to Dad, ‘You don’t want to stay here; we can’t pretend here,’ because they were loading stuff onto the wharfs, so Dad said, ‘Put me onto sick corps too.’ If they haven’t been at Blakang Mati, they would have gone to Sandakan.”

They were finally released in 1945, after four long years of captivity.

“My earliest recollection is going down to the boat to see the other boys come home,” Bill said. “It was imprinted into my brain. My grandparents were very family orientated – we had to call in every afternoon after school and every Sunday we had to have dinner or lunch; it was the 11th Commandment – and I can remember going down to the boat and seeing the boys disembarking. It was a happy day because two boys were home, but it was also really sad because two weren’t.”

Bill and his wife Tess lay a wreath in memory of his father and uncle. "It’s great," he said at the time. "It’s the first time I’ve had the opportunity to commemorate my father’s death."

The Colenso family would never be the same again.

“Nana would never accept that her boys would be killed, and she never accepted that Bill and Ray were dead,” Dianne said. “She had a weak heart and it was too much for her; she had a massive heart attack and died six months after the war ended.

“When she was dying, she died in the front room of their house where the picture of the four boys was taken before they left. She was lying propped against the mantel piece and she was struggling for breath, and suddenly she looked at the door, and said, ‘Bill, Ray,’ and then she died. And nothing on God’s earth will convince me they weren’t there waiting at the door to take her to heaven.”

Ted marched every Anzac Day in memory of his brothers until his death in 1988; he died in Sydney on Anzac Day on Anzac Parade after the Anzac Day march.

Dianne’s father Frank — haunted by the war and the loss of his two brothers — couldn’t bring himself to march until the late stages of his life.

“My dad wouldn’t go to the Anzac Day marches,” Dianne said. “My Dad had my cousin Bill and my Uncle Ted beside him all the time, but it broke him up because they marched down George Street before they left; and that’s the only time that he marched with them.”

Frank died in 2011 aged 98.

The Colenso brothers were together once more.