Remembering Rwanda 25 years later

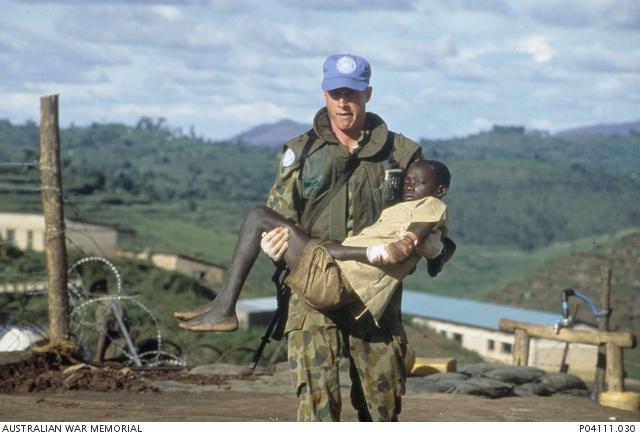

Trooper (Tpr) Jonathan (Jon) Church carries an injured Rwandan child who has survived the brutal massacre by soldiers of the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA) at the UN administered refuge camp at Kibeho. George Gittoes.

By Tracey Langner

“The world watched with horror as a tiny third world nation attempted to obliterate one race of its people.”

Decades of tension between Rwanda’s two main ethnic groups, the Hutu and the Tutsi, erupted twenty five years ago, between April and July 1994, when almost one million Rwandans were killed.

Following independence from Belgium in 1962, Rwanda was governed by the Hutu, who openly discriminated against the Tutsi. The catalyst for the 1994 genocide occurred on 6 April, when a plane preparing to land in Kigali, the capital of Rwanda, was shot down. On board were Rwandan President Juvenal Habyarimana and Burundian President Cyprien Ntaryamira, both Hutu.

Retaliation from the Hutu came in the form of systematic slaughter, of both Tutsi and moderate Hutu. The Tutsi responded with military operations, ignoring the demilitarised zone in which they were operating.

UNAMIR, the United Nations Assistance Mission to Rwanda, was completely overwhelmed and powerless to help. The international community was slow to act. Some nations, most notably the US, advocated a complete UN withdrawal from Rwanda; wariness still remained following the disastrous end to the previous UN intervention in Somalia.

It wasn’t until June 1994 that the UN Security Council sanctioned reinforcements for UNAMIR. The Australian component deployed in August. They arrived into chaos. The Rwandan economy had been destroyed, there was little functioning infrastructure, and disease was rife. The Tutsi rebel army (RPF), which had defeated the Hutu government the previous month, remained bent on reprisal.

Australia provided a 293-strong medical support force, consisting of a medical contingent with an infantry company to provide security. The first contingent completed its tour in February 1995 and was replaced by another. Both contingents served for six months.

“As part of the second contingent chosen to go to Rwanda, I travelled to Townsville to start deployment training. Three weeks were spent learning land mine recognition, resuscitation protocols, cultural differences, laws of armed conflict, weapon training and how this deployment would affect us and our loved ones.”

Lyndall Moore, a Nursing Officer, was part of the Australian Medical Support Force, which was tasked with running a hospital facility to provide health care to the 5,500 UN troops who were part of UNAMIR II. The reality for the Australian medics was that many of their patients were local Rwandans.

Lyndall Moore worked in the intensive care unit and also with the aeromedical evacuation team. An average week for the medics involved amputations, grenade injuries, car accident injuries, gunshot wounds and a wide range of infectious diseases.

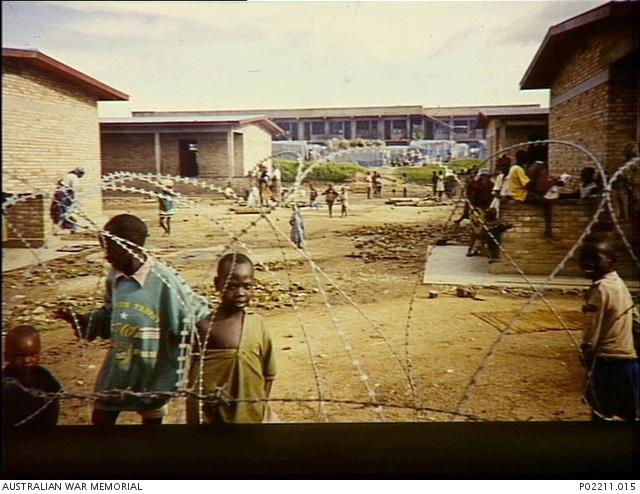

Children belonging to the Tutsi tribe standing inside a barbed wire enclosed Displaced Person's (DP) compound, Rwanda. 1995-04. Justin White.

Moore reflects that it did not seem to matter how bad the prognosis, the Rwandans were remarkably stoical: “A young woman was told that she had not only lost her leg because of the mine she stepped on, but that she had also lost the child that she had been carrying. Yet she sat there with not even a flicker, nothing but a single solitary silver tear sliding down her cheek and making a track in her dusty face.”

The civil war had ended more than six months before Moore’s arrival. In the wake of the genocide, hundreds of thousands of Rwandans were living in refugee camps. The largest camp was Kibeho, which held 80,000 to 100,000 people. Camp life was desperate. Not only was there little food or water, but the Hutu refugees were under constant harassment by the Tutsi rebel army (RFP). From 20 to 23 April 1995 the RFP began to shut down the Kibeho camp. The Tutsi government believed the camp harboured instigators of the genocide, and feared an uprising of a Hutu guerrilla army. The already tense situation deteriorated.

The Tutsi government’s action took the UN mission by surprise. The Australians were hastily tasked with getting a medical team to Kibeho. Many of the refugees were going to need medical aid before travelling. As the Australian convoy arrived at the massive camp, they drove past abandoned shelters. Rwandan army troops had already moved the entire camp population into a holding field above the church. The field, roughly the size of three football grounds, held hundreds of thousands of refugees standing shoulder to shoulder. There was no food or water. From here they were slowly corralled through a checkpoint; the purpose of the check point was to identify Hutu militia who had taken part in the genocide. Identified militia were arrested and taken away.

Refugees were only permitted medical assistance on clearing the checkpoint. Processing took days.

On the morning of 22 April the Australians arrived to continue medical aid, and found a scene of carnage; 4,000 refugees had been killed during the night, and another 400 wounded. Half of those wounded had been shot by Tutsi army soldiers, the other half had machete wounds inflicted by Hutu militia.

Over the preceding days Hutu militia members had become increasingly stressed about arrest. They had begun harassing and attacking people with machetes, for several possible reasons: creating a diversion in order to escape; silencing potential informers; forcing people to remain in the camp, providing a human shield. Whichever way, people panicked and began pushing against the tight cordon around the camp. The Tutsi soldiers responded by shooting into the crowd, on the pretext they were forestalling a riot. The numbers killed indicate the motive was less about crowd control and more about retaliation.

Shooting continued indiscriminately throughout 22 April, and the Australian medics, led by Captain Carol Vaughan-Evans, used a sandbag wall and a truck for cover while they treated the wounded. Vaughan-Evans was awarded the Medal of Gallantry for her outstanding service at Kibeho, a medal that had not been awarded since the Vietnam War.

In closing her article Lyndall Moore writes:

“I was proud to serve not only my country, but those people in that small, tropical and very angry nation. Their impact on me was in many respects profound and I will never forget those children who suffered in silence and found laughter in simple things.”