'It was pretty tough, believe me'

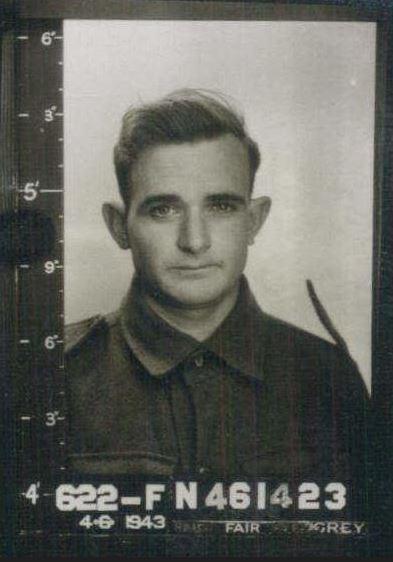

Russell during the war. Photo: Courtesy Russell Fuller

Russell Fuller was 20 years old when he landed at Balikpapan in July 1945.

It was the last major Australian ground operation of the Second World War and the largest ever amphibious assault involving Australian forces.

Russell, now 98, remembers the war as if it were yesterday. But when you mention the port city of Balikpapan, he goes quiet.

“Oh, it was pretty tough, believe me,” he said, quietly.

“They told us where we were going to go, what time we were going to land, and where we had to go, and what we had to do, so you knew what was ahead.

“But it was a worrying time because you had that many people there, and a lot of them they didn’t make it.”

Balikpapan, Borneo, 1 July 1945: Troops of the 7th Australian Division landing at Balikpapan.

The landing of Australian troops at Balikpapan, Borneo. Smoke from the ruins of enemy positions and burning oil wells is visible in the background. Shore installations were subjected to an intensive naval bombardment before the landing operation.

Australian artillerymen in alligators, amphibious tracked vehicles, making for the beach during the landing at Balikpapan. On shore, smoke from naval bombardment of enemy positions is rising.

Codenamed Oboe 2, the landing was the largest of the Oboe operations mounted by 1 Australian Corps to liberate Japanese-held British and Dutch Borneo. It was designed to secure important oil processing and port facilities and followed the earlier Oboe landings at Tarakan or Brunei Bay.

“Oh, yes, you were scared alright,” Russell said.

“We landed on the 1st of July, and ... we had to take this position.

“They gave us four days to take it, but we took it on the first day.”

Balikpapan, Borneo, 1 July 1945: Australian troops landing at Yellow Beach. Russell is pictured, second from the right.

Balikpapan, 1 July 1945: Assault barges at the beach head at the time of the Allied landing.

The 7th Division landed after a preparatory bombardment and had to fight hard for its beachhead. Concerted Japanese resistance continued for the next three weeks as the Australians advanced inland and daily engagements with Japanese forces continued until the end of the war.

“It was hard to say how you felt at the time,” Russell said. “You wanted to get in and get it finished with, but you didn’t really have much time to think about what was ahead.

“I was in a three-inch mortar patrol ... in headquarter company ... and we had to carry all this heavy equipment, and the bombs, and carry them ashore.

Balikpapan, 1 July 1945: Soldiers from a unit of the 7th Division carrying a wounded soldier on a stretcher along the beach at Balikpapan. Smoke is billowing over the beach from oil tanks set on fire by the naval bombardment that pounded the Japanese defences.

“When I came off the barge, I had a barrel on my back, and three bombs underneath each arm. The bombs weighed 30 pounds each, and then you had to have your rifle in front of you, and the barrel, or whatever you had, strapped to your back.

“You had all this with you, and then you got in to the water about so deep, and you had to wade ashore.

“It didn’t play on your mind, but you never knew what it was going to be like.

“You expected anything to happen at any time ... and you were always very wary.

“If you saw any bushes move, you stopped and went to ground, because somebody might be there looking at you, getting ready to fire...

“You were on the alert all the time and your eyes were never off the bushes.”

Balikpapan, Borneo, 1 July 1945: The view looking along Yellow Beach soon after the landing.

Balikpapan, 1 July 1945: Troops moving along the Vasey Highway during the Oboe 2 operation. Oil fires are blazing in the background.

He was surprised to see General Douglas MacArthur, Commander-in-Chief of the South-West Pacific Area, who had devised the Oboe operations.

“I didn’t expect that,” Russell said. “He must have come in when they first landed, and so Macarthur was there, and I could see him in the distance.”

Balikpapan was one of the most controversial Australian operations of the war. By this point, it was clear that Australian operations in Borneo were not contributing to the defeat of Japan, and high-ranking Australian officers considered them strategically unsound. Australian Commander-in-Chief, General Sir Thomas Blamey, advised the government to withdraw its support for Oboe 2. The government, however, stood behind MacArthur, and the Balikpapan landings went ahead, resulting in the deaths of 229 Australians and around 1,800 Japanese.

Russell had never seen anything like it.

Balikpapan, 1 July 1945: General Douglas Macarthur and Lieutenant-General Sir Leslie J. Moreshead at Balikpapan shortly after the landing.

Balikpapan, July 1945: A section of the coastline after the landing at Balikpapan, showing ruined palm tress and houses. The damage is the result of the naval bombardment before the Allied Landing.

Balikpapan, July 1945: Wrecked oil wells at Balikpapan. The damage was caused by the heavy bombardment before the landing.

Balikpapan, July 1945: Burnt out oil tanks, which were damaged during the prepatory naval bombardment.

Russell was born in Goulburn, NSW, on 1 February 1925, the son of First World War veteran Richard Fuller and his wife Grace.

The second eldest of eight children, he grew up on a dairy farm at Shallow Bay near Forster and travelled to school in Tuncurry by boat.

He was living with his sister in Bulahdelah and working at a timber mill when he was called up in June 1943.

“I got a call from the army and had to go for a check-up at Taree,” Russell said.

“A couple of weeks later they called me up and I had to get Dad’s permission to join the AIF.

“I was 18, and he just said, ‘Go ahead mate, go ahead.’”

Russell Fuller. Photo: National Archives of Australia

Russell’s father had served during the First World War and was wounded-in-action during the battle of Menin Road in September 1917. He had tried to hide the bullet wound in his right leg, dampening the pain by packing the wound with mud and dirt until he finally collapsed.

“He’d passed out, and he was put amongst the Canadian dead because they thought he was dead,” Russell said. “But he was just unconscious, and this young Salvation [Army] lassie walked past, and Dad waved his hand, and she happened to see it, and so they pulled him out.”

Brisbane, Queensland, August 1944: Troops of the 2/16th Battalion moving past the saluting base on the steps of the City Hall in King George Square during the 7th Division March through the city. Russell is pictured towards the back right and is identified by the number 18. Photo: AWM 068288

Russell went on to serve with the 2/16th Battalion.

“We did our training up on the tablelands of Queensland at Tolga, and then we did our barge training at Trinity beach, outside of Cairns,” Russell said.

“It was rugged at times, and we went through a lot.

“One part is never out of my mind. We were lined up for dinner, and they were serving, and we were lined up getting our meal, when we had what we called a drop shell.”

An artillery battalion had been practicing when a shell fell short of its target.

“It dropped in front of us, and bang, that was it,” he said. “It killed six of us, and I was about four back from the last bloke who was killed.

“They called the exercise off, and we all went back to camp, but it played up on a lot of us.”

The battalion would spend more than a year training for its final campaign of the war.

“We went to Morotai first,” Russell said. “And they told us where we were going to go and what we had to do.

“They’d given us these old steel helmets to wear during the war and we all threw them away.

“They were hot, being in the tropics, and they were boiling on your head, so we threw them away and put the old slouch hats on ...

“They were much better. And that was just the risk you took.”

Morotai, 30 May 1945: A truck of the 2/16th Transport Platoon being guided up the ramp of a landing ship tank (LST) for transportation to North Borneo.

He recalls being on guard duty at Morotai, and thinking about the future.

“They had movies every night, but the funny thing is ... you wouldn’t believe it, the sergeant and I, we missed out all the time,” he said.

“We ended up on guard duty every time, so we never saw any pictures, and we didn’t go to any of the movies ...

“But he came from Western Australia, and was off the farm, so we had great old chats about the farm and what we were going to do after the war.”

Russell was on patrol on the north coast of Borneo when he learnt the war was finally over. He remembers the men all flinging their felt hats into the air, hitting the palm fronds above them.

“Oh, it was terrific, believe me,” he said.

“We were about 80 miles up from Manggar, searching for the Japanese, when we got word the war was over.

“What a great feeling it was, knowing nobody was going to attack. You weren’t going to get shot at. You weren’t going to get ambushed.

“So it was a great feeling, believe me, and then when we came back to the base, and they gave us a couple of bottles of beer to celebrate.”

Russell went on to serve as part of the occupation force after the war, before being discharged in October 1946.

“It was terrific,” he said. “I came home on an old ship, the old Katoomba, and we went into Sydney. I remember coming through the heads, and looking at the old Harbour Bridge in the distance.

“You felt lucky, you really did. The war had ended, and so you had that terrific feeling. You had no more worry that you might not come home, that you might get killed.

“Everything was back to normal, and you had the wonderful feeling that you were safe once again ...

“It was a terrific feeling ... not feeling like you were waiting for something to happen ...

“All the dangers and that were over and you could look forward to the future, not to the past, and so it was great coming through the heads there in Sydney ...

“I can still see my mum running down the farm when I got home and giving me a big hug. She’d ran down the hill to meet me after the war ... and that was special.”

Russell with his wife on their wedding day. Photo: Courtesy Russell Fuller

Russell with his wife Jenny after the war. Photo: Courtesy Russell Fuller

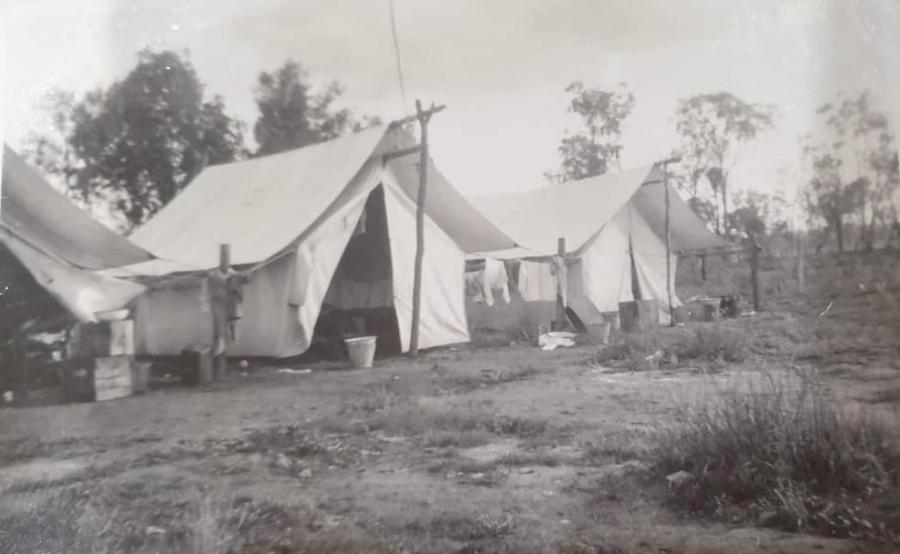

The tents where Russell lived while laying telephone cables for the Postmaster-General's Department. Photo: Courtesy Russell Fuller

Russell went to work in a factory after the war, and put in for a soldier settlement block in Queensland with one of his cousins, “but when we went up there, somebody had beat us to it.”

He returned to Rockhampton and found work laying telephone cables for the Postmaster-General's Department.

“That was one of the greatest jobs in the world, that one,” he said. “We were digging trenches, putting telephone lines in ... and we used to go everywhere.”

He met his wife, Jenny, through his sister, Yvonne. The three of them went out for dinner several times before he worked up the courage to ask Jenny if she would go out with him. When she said yes, Russell recalls, “That made my day ... She’s the best thing that ever happened to me.”

They married in November 1952 and adopted two girls, Michelle and Debbie.

Russell visiting the Memorial.

Today, Russell lives near Wollongong and is grateful for his blessings.

He travelled to the Australian War Memorial in Canberra with his daughter Michelle and laid a wreath at a Last Post Ceremony in memory of his mates.

More than 75 years after the end of the war, he still considers himself fortunate to have survived.

“I had a lot of good friends in the army,” he said, quietly.

“And it brings back a lot of memories, good and bad. But you do feel lucky.

“If everybody was there to help one another, what a wonderful world it would be.

Russell laid a wreath in honour of his mates at a Last Post Ceremony at the Memorial. He is pictured with his daughter Michelle.

“Look after one another, that’s my outlook on life. I want nothing in return. If I can do you a good deed today, that makes my day ...

“We don’t want to go through another world war ... The suffering that people went through. All those mothers and fathers who lost their kin. It plays on your mind. What must they be thinking on Anzac Day? What must they think about the war?

“So yes, it brings back bad memories at times, believe me ...

“But I think it’s important to remember what happened during the war.

“And that way you never forget them.”