'It just shows you my luck, or whatever you like to call it.'

When Barney Cain heard Japanese bombers flying over Rabaul, he thought he was going to die.

“I was actually in hospital there with malaria when the first Japanese Kawanishi bombers came over and bombed us,” he said.

“I thought they were going to drop right on us ... right on my head ... but they didn’t.

“It just shows you my luck, or whatever you like to call it.”

When the Japanese landed at Rabaul on 23 January 1942, the small Australian garrison was quickly overwhelmed and most of its troops, including six army nurses, were captured. About 400 troops, including Barney, evaded capture.

“By that time we were running from the Japanese and you had one thing on your mind – feet, do your duty.”

The eldest of seven children, Barney Cain enlisted in Melbourne in 1940.

Barney spent the next three and a half months evading the Japanese, crossing rivers, and trekking through the rugged mountains and jungles of New Britain in a desperate attempt to escape.

A few years earlier, he’d been a teenager playing football and cricket at Rye on Victoria’s Mornington Peninsula. His great-grandfather was one of Rye’s early settlers, and Barney was born at the home his grandfather built on the family property, ‘White Cliffs’.

He was working as a farm labourer and playing football for Sorrento when he enlisted during the Second World War. He smiles when asked why he decided to join up.

“Because I was an idiot,” he said, laughing.

“I was going to join after the footy season in 1940, but I was playing football, and I hurt a muscle in my leg. I couldn’t kick right footed – and I’m a right footer – so I decided then that if I couldn’t play footy, I was going to join the army.

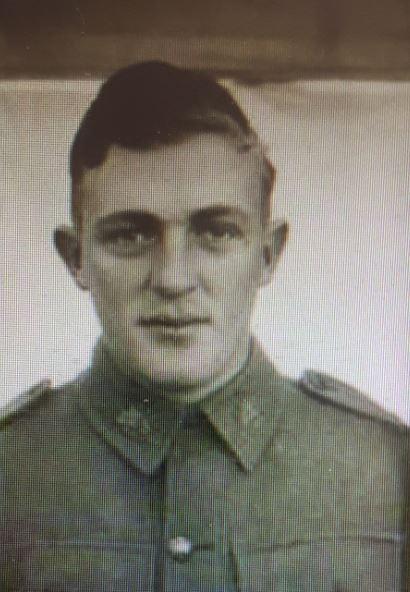

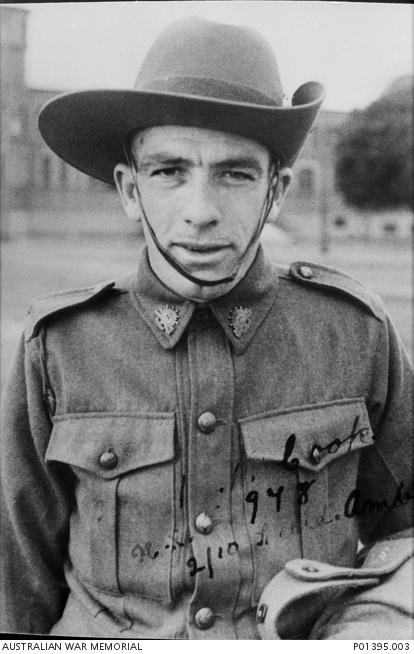

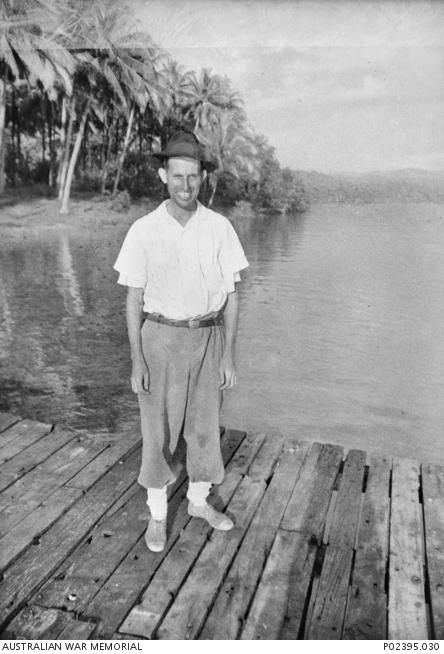

Barney Cain during the war. Photo: Courtesy Barney Cain

“I went and joined up at Melbourne Town Hall sometime in late May, and I passed all the medicals and everything, but I was only 19 at the time, so I had to go and get my parents’ permission.

“My father was in World War I and lost an eye on the Western Front in France.

“He was in the army in the Second World War too – one of the volunteers – and he signed it immediately, but my mother didn’t want to sign it.

“I don’t blame her – she had more brains that the two of us – but anyhow, it was signed, and that was it.”

He reported to the Brighton Drill Hall at 9 am on 6 June 1940 – his 20th birthday – and was sworn in at Royal Park. Having volunteered to join the 17th Anti-Tank Battery, he was sent to New Britain with Lark Force in April 1941. He was there when the Japanese began bombing Rabaul on 4 January 1942.

Air raids continued almost daily until the 5,000-strong Japanese invasion force entered the harbour and landed at Blanch Bay in the early hours of 23 January 1942.

The 1,400-strong Lark Force was under-resourced and under-prepared, and could only offer token resistance.

The town was captured in just a few hours, and more than 800 members of Lark Force were taken prisoner by the Japanese.

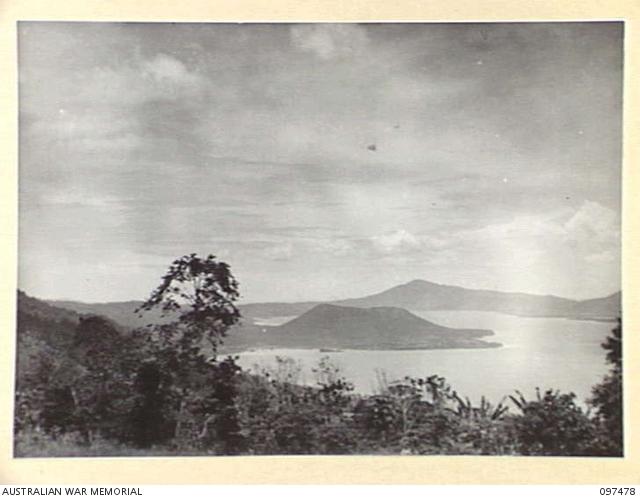

Blanche Bay, Rabaul area, New Britain, September 1945: A panoramic view of Blanche Bay and Simpson Harbour looking north.

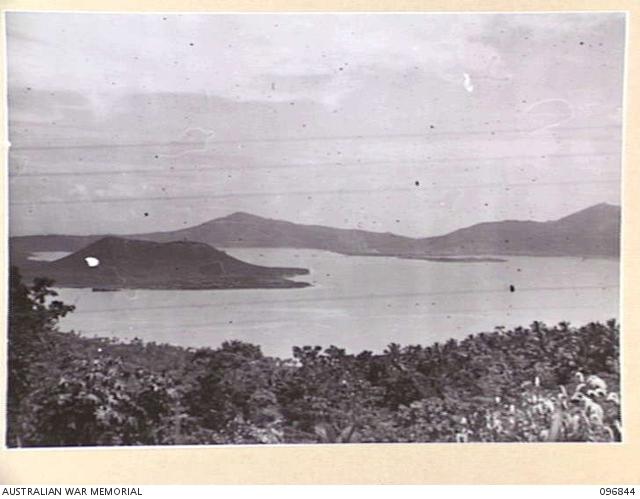

Taliligap, New Britian, September 1945: The view of Simpson Harbour with the crater Vulcan in the foreground. This scene was taken after Australian troops occupied the area following hte surrender of the Japanese.

Barney was one of the lucky ones. Having just rejoined his unit after being discharged from hospital the week before, he escaped to the south side of the island.

“I was a driver for a lieutenant who was in charge of one of the troops,” Barney said.

“We were down near the Vulcan, a volcano that went up in 1937, when the Japanese landed.

“They landed in the dark, just down from us, at about 3 o’clock in the morning, and when it just came daylight, he said to me, ‘You’d better take the ute up to the top.’

“It was steep and slippery, and we didn’t know what had happened up there, so I went up there to have a look, but he never turned up.

“Eventually, some of the New Guinean Volunteer Rifles came up the hill, and I asked them where the anti-tank blokes were.

“They said, ‘There’s no one there,’ so eventually we put them on a truck and we landed at what we called the Upper Drome.

“That’s where everybody was heading, and there was an officer there – Mad Mick – screaming out.

“He was the 2/22nd major, and he was yelling, ‘It’s all over, it’s every man for himself,’ which was great news to us; we’d had orders – you fight to the last, there’s no surrender, and all this.”

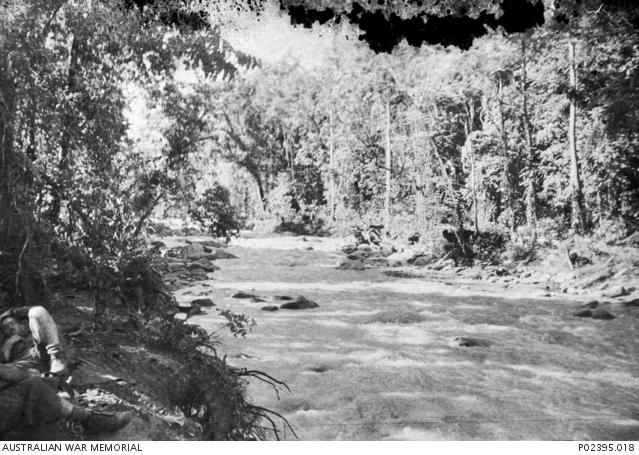

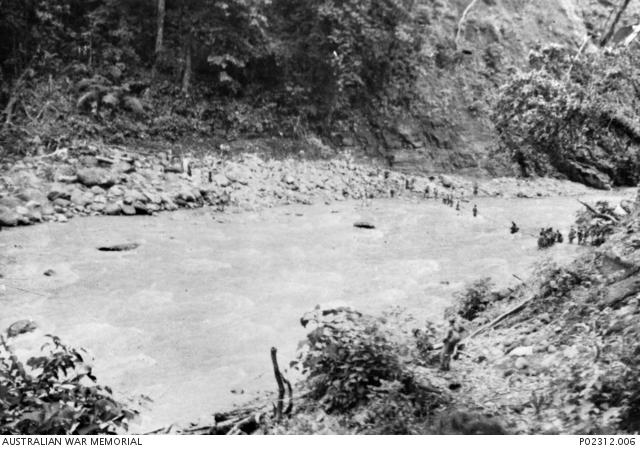

Adler River, New Britain, January 1942: The Adler River in the Bainings Mountains on the eastern side of the Gazelle Peninsula, an obstacle to the Australian troops retreating from Rabaul. The party was making its way south to Palmalmal Plantation and rescue in April 1942. Note the soldiers resting on the river bank in the far left of the photograph.

Adler River, New Britain, January 1942: The Adler River, in the Bainings Mountains on the eastern side of the Gazelle Peninsula, an obstacle to the Australian troops retreating from Rabaul after the successful attack by Japanese forces. This is the point where at least two parties of retreating Australian troops crossed the Adler River. The first party of 21 men from the Anti-aircraft Battery Rabaul and the 17th Anti-tank Battery crossed here on 26 January securing a lawyer vine rope across the river.

In the ensuing days, groups from the 2/22nd Battalion, ranging from company-strength down to pairs and individuals, desperately tried to escape along New Britain's north and south coasts. Some found small boats and got away under their own auspices, while others were picked up by larger vessels operating from New Guinea.

“We were strafed and everything trying to get out,” Barney said. “We finished up at Malaguna, but that was as far as we could get, so from there, we headed across the [Bainings] Mountains to Adler Bay on the south side of the island.

“I finished up at Tol Plantation, and I was there when the Japs landed there too.”

One hundred and 60 Australians would be massacred at Tol, their bodies left in the jungle.

Barney remembers the moment the Japanese arrived as if it was yesterday.

“There were a lot of troops there, all in these small parties, and a Major Bill Owen was organising to get everyone over to the other side of the river,” he said.

“The natives were going to ferry us across in canoes, and around the corner came these barges.

“Someone said, ‘They’ve come to rescue us,’ but I had a pair of binoculars, and I won’t tell you what I said first.

“I said, ‘No, they’re Japanese,’ and they let us know then. Boom, boom, boom. They started firing – I think they were mortars – and it scattered the natives, so they abandoned us, and took off in the canoes.”

Bainings Mountains, Gazelle Peninsula, New Britain, January 1942. Some of the Australian troops retreating from Rabaul after the attack by Japanese forces on 23 January 1942 take a rest on a track through the Bainings Mountains.

Bainings Mountains, New Britain, January 1942. Australian troops rest while retreating from Rabaul after Japanese forces attacked on 23 January 1942.

Men were captured as they tried to escape from the plantation, others were captured when they were unable to cross the rivers in the area, and at least one group surrendered. The prisoners of war were tied together in groups of two or three. They were asked in sign language by the Japanese if they preferred to be shot or bayoneted and were then taken into the jungle where they were shot, bayoneted or burnt alive.

Barney’s party had managed to escape when the Japanese arrived.

“There were about 16 in my party, and half of them took off, and headed up river,” he said.

“We were held up for a while, and when we started off, I saw a track leading off the main track that I was going up. I headed down there, and here’s the canoes.”

Using the canoes, the men made it across the river, and were walking across an open area when they saw two barges leaving from the other side of Wide Bay.

“There were only about eight of us left by then, and one of the other blokes said, ‘They’re taking prisoners back to Rabaul,’ and then – boom, boom, again – they shot at us,” he said.

“They were not taking prisoners back; they were heading over to our side, but then they swung off, and headed off further up the bay, so we took off up into the hills and stayed there overnight.

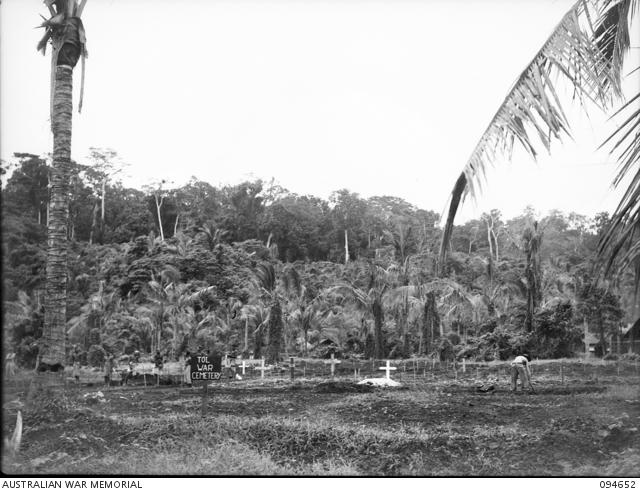

Tol Area, New Britain, August 1945: Troops at work in Tol cemetery. Members of 2/22nd Battallion who were massacred by the Japanese at Tol Plantation are buried here. Crosses for the graves are not yet ready.

“The next day, we came out, and we headed off, but we never saw a Jap or anything. We made sure we didn’t.

“The Japs were patrolling in that area, and any noises we heard, we got out of the road, and headed up in to the hills. They could have been Jap troops, or not, but they’d been into the village there, and the village didn’t want to have one bit to do with us.”

The men pushed on to a village where the villagers sheltered them for the night, and eventually made it to Pal Mal Mal at Jacquinot Bay.

Father Ted Harris, a Roman Catholic priest who ran the Mal Mal Catholic Mission, did everything he could to help the Australian troops who stumbled in from the jungle, giving them food, shelter and medicine as they hid from the Japanese at the Drina and Wunung plantations.

Barney and his mates tried to push on further, but were forced to return to Drina River when they got to a river they couldn’t cross.

He remembers seeing Bill Cook, a private from Campsie, who had been bayonetted 11 times during the Tol Plantation massacre. He had been stabbed five times, his hands tied behind his back, and survived by holding his breath and pretending to be dead. When he could hold his breath no longer, a Japanese soldier heard him, and stabbed him a further six times. The last thrust went through his ear and into his mouth. As he lay there, he heard the last two men being shot. When the Japanese finally left, he untied the cloth that had connected him to his dead mates with his teeth and staggered towards the sea. He walked in the water to avoid leaving a trail of blood and was found the next morning by a small party of soldiers with Lark Force area commander Colonel John Scanlon who dressed his wounds.

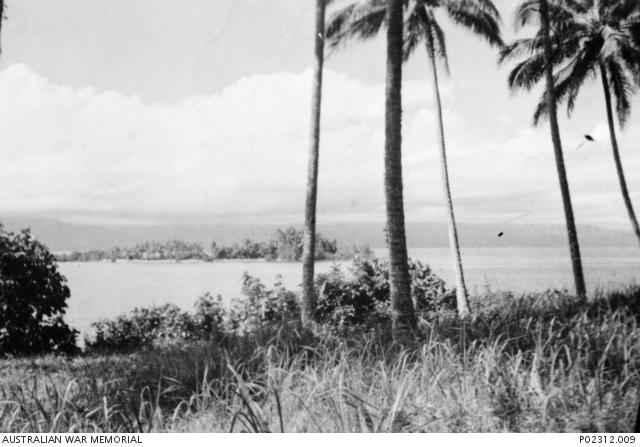

Palmalmal Plantation, Gazelle Peninsula, New Britain, April 1942. Jacquinot Bay, seen from Palmalmal Plantation, from where HMAS Laurabada evacuated over 150 troops and civilians who had retreated south from Rabaul.

By April 1942, 156 Australian soldiers and civilians had escaped to the Pal Mal Mal area after fleeing Rabaul. They were eventually rescued and evacuated to Port Moresby on board HMAS Laurabada.

“The Japs had started to build up in front of us at Gasmata, so we were blocked; we couldn’t go any further, and we couldn’t go back – we were stuck there,” Barney said.

“And that’s where they were trying to get in touch with Moresby. They had a wireless, but they couldn’t reach Moresby with it.

“Some of the other blokes had got off on the north side of the island, but we were stuck on the south side.

“Two Australians – I think they were officers– and two natives volunteered, and came across in a yacht and found us, or found the Pal Mal Mal area.

“There were quite a few of us, and they sent back word of how many troops were there, and they sent the Laurabada to come and pick us up.”

Private Bill Cook survived the Tol Plantation massacre after being bayonetted 11 times.

His body wracked with malaria and dysentery, Barney walked from Drina River back to Pal Mal Mal to board the Laurabada.

“I reckon I had at most a fortnight to live, but I made it back to Pal Mal Mal, and we got on that boat, and we landed in Moresby,” Barney said.

“We got on the Macdhui, which was a boat that used to do the island trade, [to go to Townsville] and I had a pair of shorts on, and that was all I had. I had no boots, and we got on, and – dong, dong, dong, dong – everybody started heading for the dining room.

Jacquinot Bay, New Britain, 9 April 1942. HMAS Laurabada moored in the mangroves of Jacquinot Bay just off Palmalmal Plantation.

Port Moresby, April 1942. HMAS Laurabada arriving at Port Moresby carrying 156 evacuees from New Britain..

Port Moresby, April 1942: Evacuees crowd the rails of the HMAS Laurabada as the ship draws into the wharf.

“It was the bell for dressing for dinner, but we’d been three months in the jungle in the same clothes all the time, or what was left of them.

“We hadn’t had a feed in months, and they plonked a loaf of bread on the table for the steward to open. When they came back, we asked if we could have another loaf of bread to eat, and the steward said, ‘You’re lucky, there’s roast turkey tonight.’

“We had roast turkey with all the trimmings and everything, and of course, you eat and eat and eat, but it’s not very good for you when you put that much food in because your stomach is only that small, so I gave that away, and I didn’t eat like that for the rest of the trip.”

Port Moresby, April 1942: Evacuees from New Britain boarding the troopship MV Macdhui to sail to Townsville.

Barney went on to serve with the 2/4th Battalion during the Aitape-Wewak campaign. Three of his younger siblings also served during the war: his brother Jimmy served with him in the 2/4th Battalion until he was struck down by Dengue fever; his sister Sally served as a corporal in Signals; and his brother Mick served as a postmaster in the air force.

Barney was in Wewak when he was told he was going home. He remembers walking out of Melbourne’s Flinders Street Station in August 1945 to learn that the war was over.

“It was 9 o’clock in the morning and an elderly lady came up to me, and threw her arms around me, and said, ‘It’s all over.’

“I thought,’ Geez, she’s started early this morning,’ and the next minute there were hundreds of them out there – the war was finished.”

Barney returned to his family in Rye, and met his wife Betty on a double date with his cousin. They were married on 26 April 1947. They had three children – Barney, Dennis and Jeffrey – and spent time in Queensland before returning to Cain Road in Rye where they lived for almost 30 years.

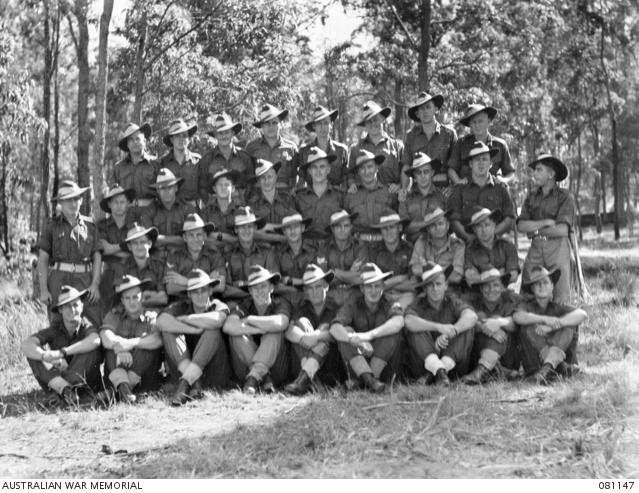

Queensland, October 1944: Group portrait of the personnel of No. 10 Platoon, B Company, 2/4th Infantry Battalion, 19th Infantry Brigade. Barney is pictured, front row, fourth from left, next to his brother Jimmy, front row, fifth from left.

Today, Barney still lives independently, enjoys dabbling in new technology, and likes to swing a golf club from time to time. He celebrated his 100th birthday earlier this year and has seven grandchildren, 12 great grandchildren and one great-great grandchild.

“People say, ‘I was that scared,’ but I can’t say I was ever really scared,” he said.

“You get revved up a bit, and ... you get to the point when you are ill, and you are that crook, that you start to worry a bit whether you are going to make it or not, but I couldn’t say I was ever that scared…

“It’s weird, but you get to the stage that you are just accepting of it – I might get killed tomorrow –and I’d say the big majority of blokes were like that.

“As a unit, you depend on one another for your whole life, and if you don’t work together, there’s every chance you are going to die.”

Barney will never forget those who helped him during his three and a half months evading the Japanese in the mountains and jungles of New Britain. Father Harris, the man who had helped so many at Pal Mal Mal, was later taken by the Japanese and executed at sea. His body was dumped overboard and eventually washed up on the shore. The Japanese would not allow the locals to bury his body which eventually washed out to sea. A memorial, provided by grateful survivors of the 2/22nd Battalion, was erected on the beach after the war with the simple inscription: “I was sick and you visited me.”

Palmalmal Plantation, Gazelle Peninsula, New Britain. April 1942. Father Edward (Ted) Harris at the Palmalmal Plantation wharf just before the departure of HMAS Laurabada for Port Moresby carrying 156 survivors from Rabaul. Father Harris, a Roman Catholic priest, ran the Malmal Catholic Mission at Jacquinot Bay.

More than 75 years after the end of the war, Barney remembers it all, including his army number –VX30679. He still has his dog tags, and gets emotional talking about his mates, and how young they all were.

“There’s no way you would have got me to tell you all this after the war,” he said.

“I didn’t talk about it up until recently, but I think it probably helps to get things off your chest, doesn’t it?

“I always thought of my mother afterwards. They were informed that I was missing-in-action, and well, my father was in World War I, so naturally, he knew straight away what that meant, and then they said I was missing for three months; he thought I was dead.”

Today, Barney is known for his witty one-liners and his home-made bread. Looking back, he still considers himself fortunate; fortunate to have survived the three and a half months in the mountains and jungles of New Britain, fortunate to have married the love of his life, and fortunate to have had a sense of humour and zest for life that helped him through it all.

“I’d tried too hard to stay alive,” he said. “You’re not going to waste it, are you?”