'I was lucky'

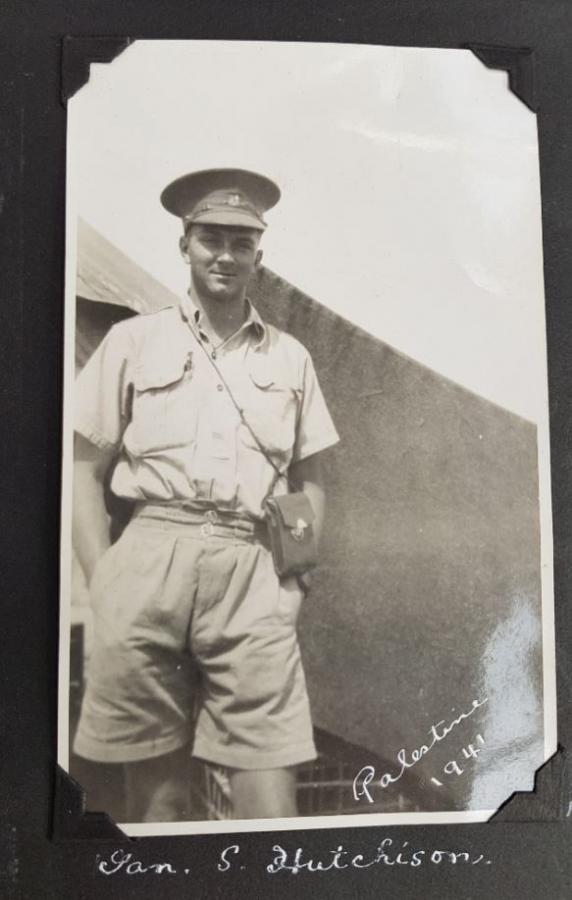

Eighty years after the start of the Second World War, Ian Hutchison still considers himself lucky: lucky to have survived the war in the Middle East and New Guinea; lucky to have married the love of his life; and lucky to have celebrated his 100th birthday with friends and family.

“I think to get to 100 you have to have a bit of luck,” the Second World War veteran said, laughing. “So, yes, I think I’ve had a bit of luck.”

A farmer’s son from Queensland, Ian was born in Toowoomba in the aftermath of the First World War and was teaching at a school in Texas on the Queensland border when war broke out in September 1939.

“People at that time thought the war would be over in the new year,” he said. “People like me thought we’d miss out on an adventure, so instead of waiting to be called up, we joined the army.

“I had always thought of England as our mother country, and I just wanted to do my bit.”

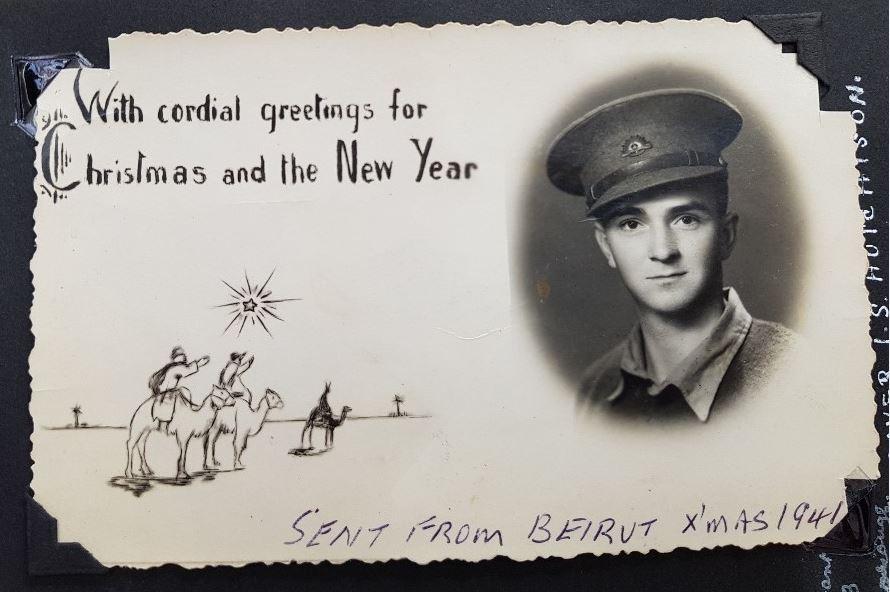

Ian with his brother Keith.

Photos: Courtesy Ian Hutchison

He had just turned 20, and needed his parents’ permission to enlist. “They were intelligent people; they knew something had to be done,” he said. “They didn’t like to see their sons going away, but it had to happen, and that was that.”

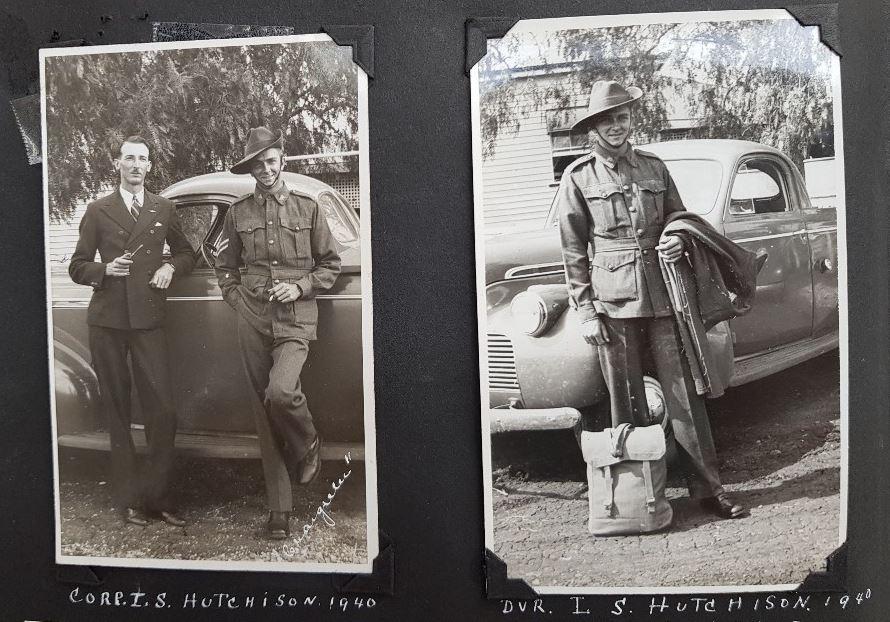

Ian enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force in July 1940 and his brother Keith joined the Royal Australian Air Force, becoming a navigator and group photographer responsible for surveillance and reconnaissance work.

Ian remembers enlisting in the Second AIF as if it was yesterday.

“There were five of us, and we hired a car in Texas and went down to a town called Warwick to enlist; we were in uniform nine days later, but the other fellows all went to Burma, and only one came back,” he said.

“We were taken to a big grass paddock in Brisbane and I had five months training with the infantry, but one afternoon a couple of officers came over from a place near Brisbane, and asked our company to fall in. We wondered why, and then one of the officers said, ‘All those who can drive, take two steps forward.’ In those days, not many people could, so I took two steps forward, and a few other fellows did too.”

Ian and his mate John Howard showing their blisters at the AIF camp in 1940. John was the only one of Ian's mates to return from Burma.

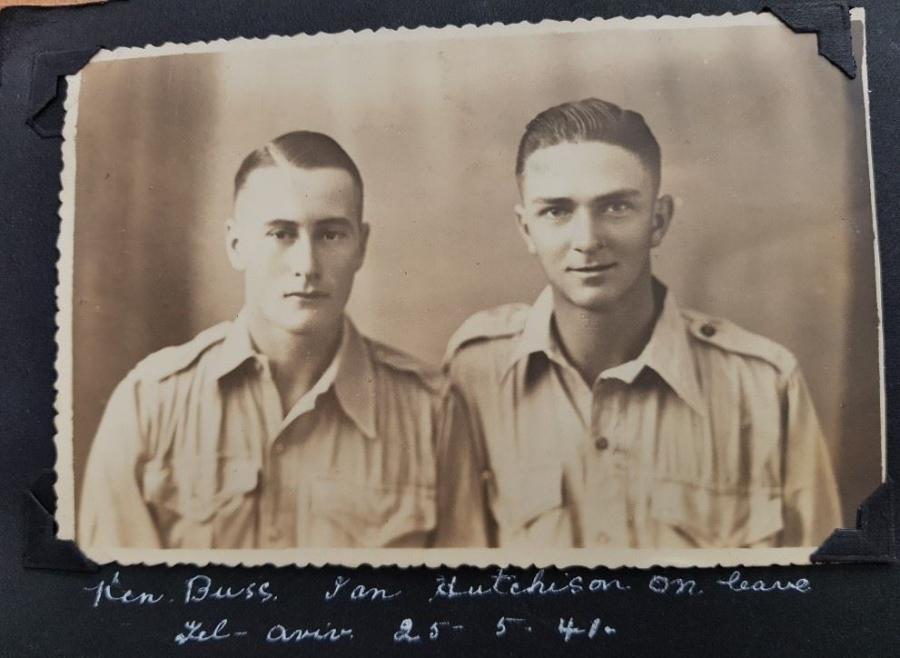

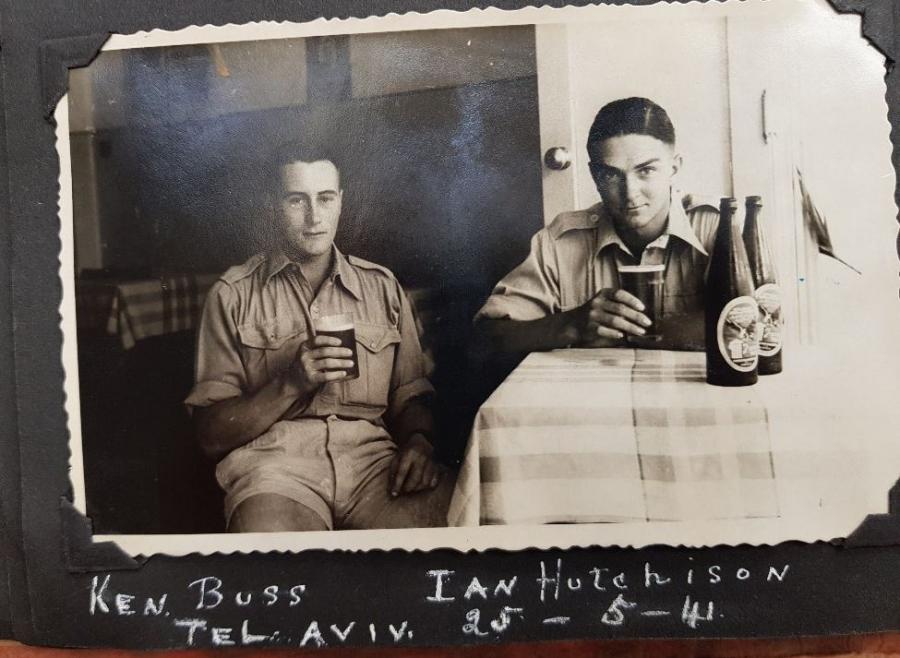

Ian served with his mate Ken Buss throughout the war.

It was a decision that would change his life. He became a driver and met one of his best mates, Ken Buss. The pair served through the war together and became lifelong friends.

“We went to Redbank camp and I walked into the hut and this fellow next to me just threw his palliasse – the hessian bag full of straw that was our bed – on the floor,” Ian said. “I threw mine down next to it and we became friends right from that very minute. We were both from the land and it just so happened we were alongside one another … and there we were; we were never split up.”

The next day they were sent to Sydney where they embarked for overseas service on the troopship Queen Mary. Ian still has a coat-hanger from the ship which he souvenired during the war as a reminder of the voyage.

“It was a wonderful ship, that one,” Ian said. “I used to still get lost after a week. I thought it was fairly crowded, but there were only 6,500 troops on it, plus the crew. My brother was on it later on when he went to train in Canada with the air force, and there were 18,000 troops on the ship plus the crew then.”

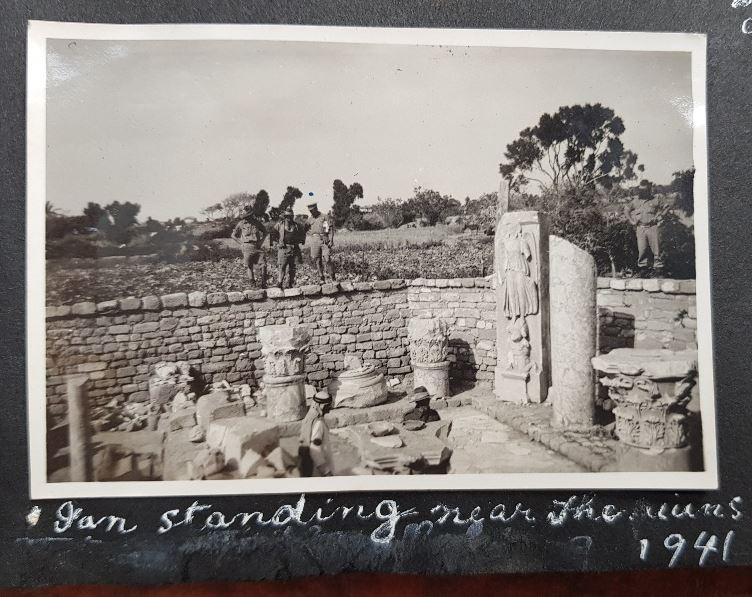

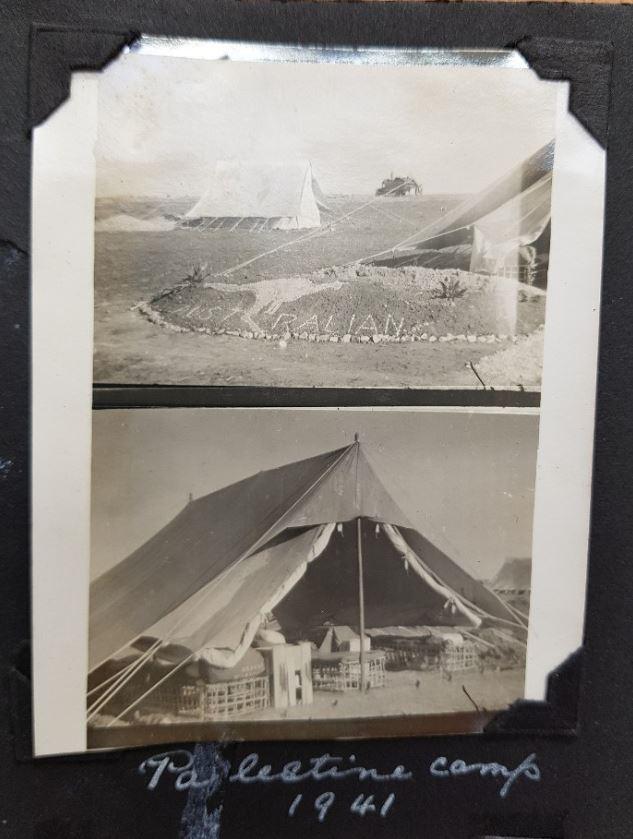

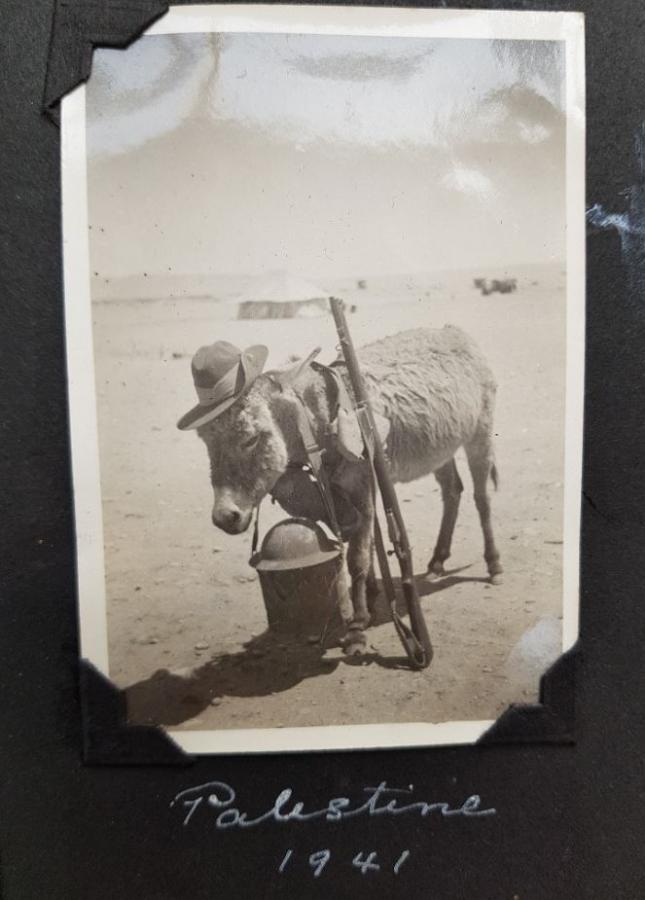

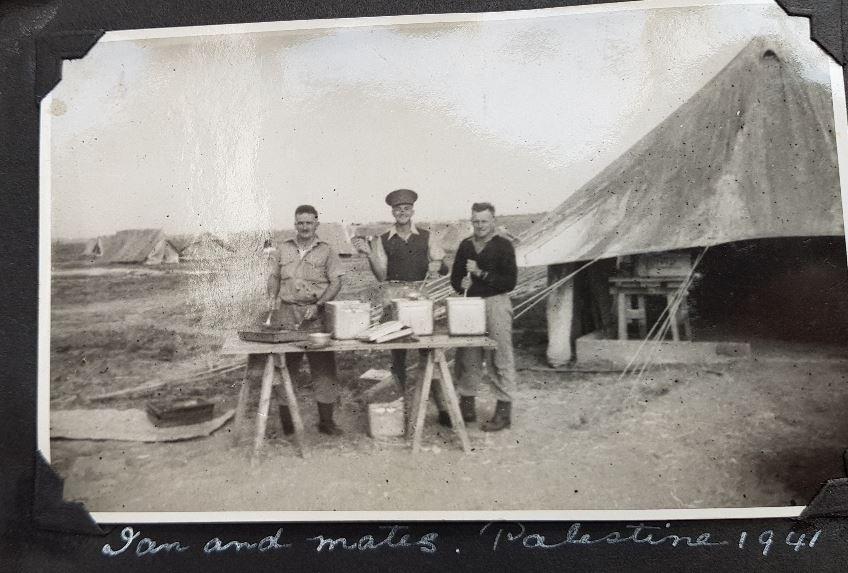

Ian was transferred to a hospital ship when they reached Ceylon, now Sri Lanka, after contracting the mumps. He was eventually reunited with his unit in Palestine, where they were “waiting to go to war”.

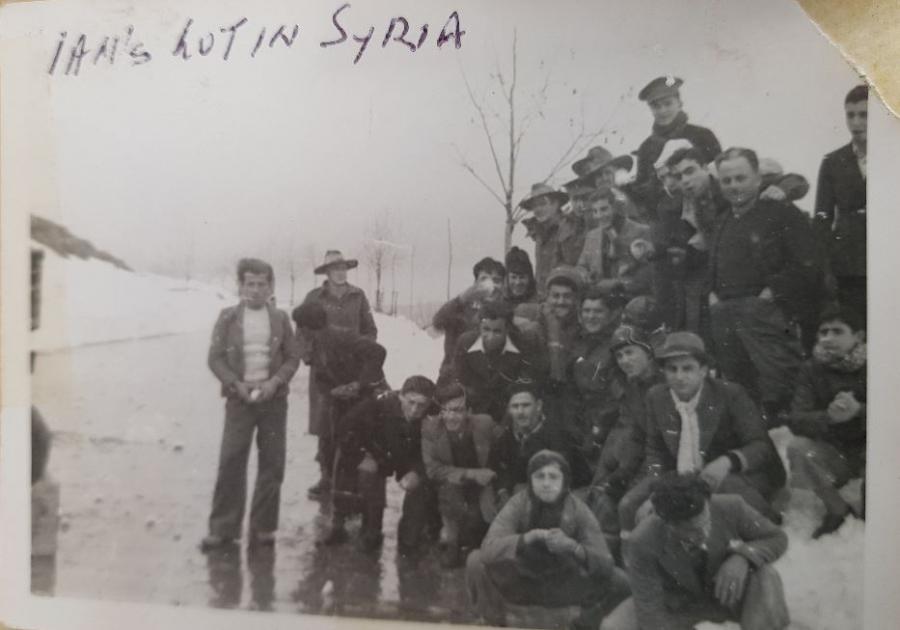

“They had a tremendously big camp there,” Ian said. “We were split up into three detachments: one went up into the desert; another went to Greece and Crete; and the third did the Syrian show.

“It wasn’t real good in Syria; there were only 35,000 of us up there, and the opposition had about the same. They were nearly all Frenchmen – they called them Vichy French – but they had German officers from Africa and other places.”

Ian served as a driver with the supply company and was the orderly room corporal for headquarters.

“Being in the trucks was the pick of the jobs; it really was,” he said.

“Being a supply unit, we had to supply all the stuff needed to fight a war; there’s no good having a whole lot of men if they’ve got no ammunition or food. They were the two most important things, ammunition first, and food second.

“We had 20 per cent casualties in five weeks up there, and they lost about the same.

“The planes used to have a go at us, but up there the roads weren’t straight enough to really have a good go at it.

“They still used to try, but you need a fair bit of straight stuff for an aeroplane to shoot you … and we only lost a few trucks.

“They said, ‘If you see one in the distance, leave your truck and run like hell for 100 metres and hide, so they won’t strafe you.’

“What we did up there was we made little dumps; we’d make a dump under an olive tree in an orchard somewhere, and then about half a mile away we’d make another one, so that we had a whole lot of them, and as our crowd would start to advance, we’d pick up the furthest one and take it up closer to where we were, and that sort of thing.

“The trucks had a trap door on the roof as well, and your offsider would stand on the seat, and go up through the trap door. We had a machine-gun on the front, on the top of the cabin, but that was useless too because you can’t do much against a plane like that.”

He laughs when asked if they were frightened.

“I don’t know about being frightened,” he said. “They say if you are a serviceman – it doesn’t matter if it’s army, navy, or air force – service is 90 per cent boredom and 10 per cent terror. And that’s about right.”

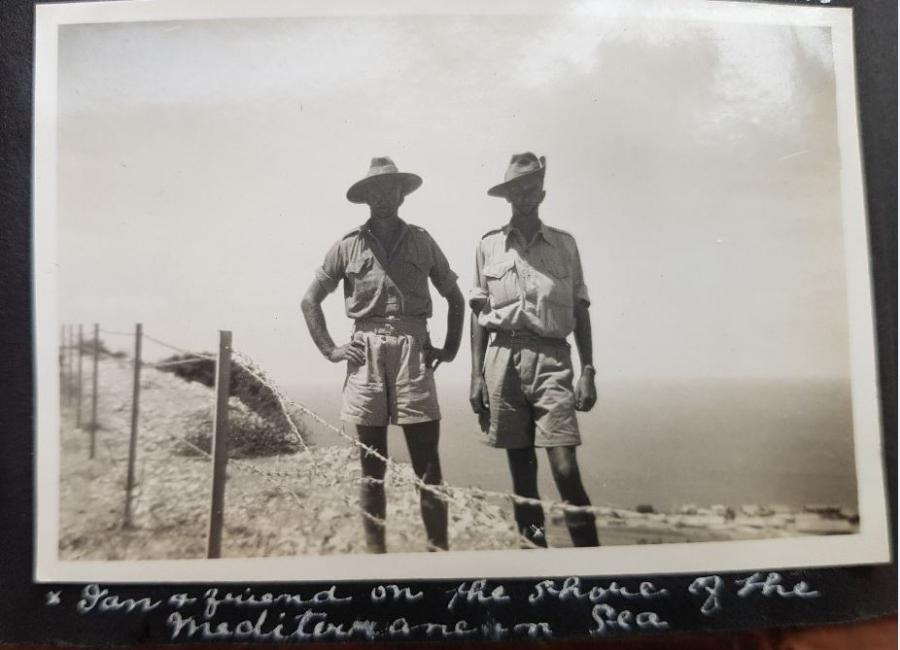

Ian’s war was only beginning. After serving in Egypt, Palestine, Syria, and Lebanon, he was sent to New Guinea when the Japanese entered the war.

“We were up there in Beirut, when we got a message saying, ‘Pack up, you’re leaving.’ We thought we were going home, but we went down to Port Said, and we hung around for three weeks waiting for a ship,” he said. “Instead of going home, we were going to Java, but we were lucky our ship was slower; it was late and the Japs took Java before we got there.”

Instead, they took 53 days to get to Adelaide before making their way to New Guinea.

“We went up there when the Japs were looking down on Port Moresby,” he said. “They were about 20 miles up the hill when our ship got into Port Moresby and they reckon the Japs could see us, but I don’t see they could.

“Moresby; there wasn’t much left it. They kept bombing it, and the Yanks – the Americans – had an aerodrome seven miles out and they used to bomb it all the time too.”

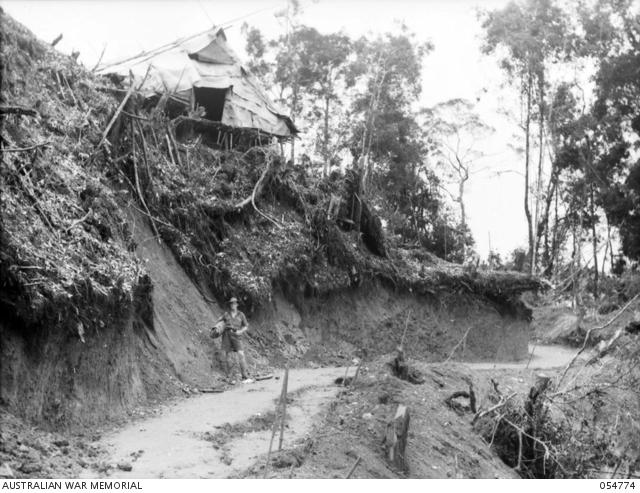

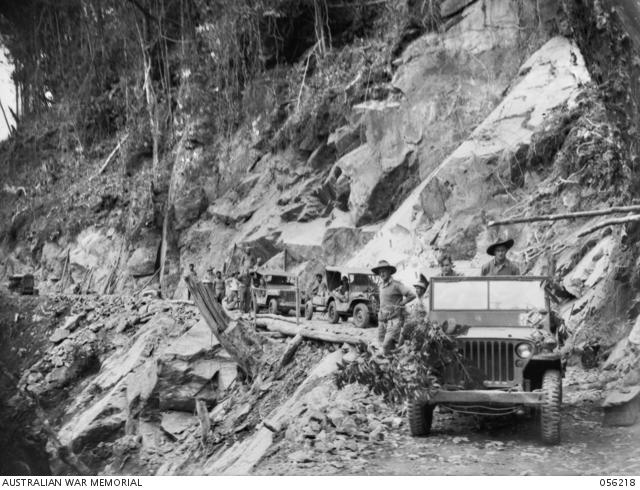

Ian was sent along the south coast of New Guinea to the Bulldog River where he drove supplies over the Owen Stanley Range to Wau and Lei.

“They had a track up there called the Bulldog Track,” he said. “It was only a walking track for the local people, but we had an engineer company, plus a whole lot of their local labourers, and they built this road up over the mountain. It was over 10,000 feet, and 88 miles mind you, but they built it in eight months, by hand, with no machinery, and it was good enough for our jeeps and our trailers to drag stuff up the mountain and down the other side.”

It was difficult terrain and the jungle would quickly reclaim any track that was left for any length of time.

“If you didn’t maintain a track, in about three weeks it was overgrown,” Ian said. “The stuff up there, it’s amazing; it just grows while you look at it. It’s hard to describe, and it’s so damn thick …

“In some places you would have to cut the trees down; if they were reasonable you would just have to lay them across the road; otherwise you had to split them in halves and make your road that way.

“You might have to go a couple of hundred metres on these logs, and that was one of our troubles; the springs and the spring shackles on the jeeps used to just collapse, and it was hard to replace them. We had jeeps stacked on top of one another just waiting for parts.”

Landslides were another regular hazard that they faced as they battled to keep the troops supplied.

“It rained every day of course, and with all the rain they got up there, you would have to get out your shovel, and shovel [the debris} off the road so that you could drive over it.”

He remembers being hungry all of the time and fighting off the mosquitoes in an attempt to avoid malaria.

“It wasn’t a good place,” he said. “Up in New Guinea, we didn’t see any fresh meat or bread for nearly 12 months. It was all tinned stuff, and we were hungry all of the time.

“I had dengue fever, but a lot of people got that. Down near the coast the mosquitoes were terrifically big and there were plenty of them. I was lucky I didn’t get malaria because we had to take Atabrine every day. They used to line us up and make sure we took the tablets, and when we went back to Brisbane where there were a lot of troops about we found they had an odour and a green tinge on their faces from the Atabrine.”

He was “having a spell” on the Atherton Tablelands in Queensland when the war finally ended.

“Oh, it was wonderful, I can tell you,” he said. “It was a wonderful relief. I happened to be in Brisbane when the European war finished and it was pretty wild down there that night too, but it was a great feeling; I don’t know how to describe it.”

After everything he experienced during the war, he still believes the best thing was “getting home safely”.

After the war, he married his wife Joan, and returned to the land, farming on the black soil plains of the Darling Downs. Together they had four children – Jan, David, Brett and Kym – 11 grandchildren, and 10 great-grandchildren. He was widowed in 1994 after a long and happy marriage and continued to work as a grain sampler until he retired at 83 due to ill health.

But he never forgot those he served with, attending Anzac Day Dawn Services for as long as he could.

“That’s the least we could do for those poor fellows who didn’t get back,” he said. “And that’s what I often think: when you go and see those parades, who thinks of all those who didn’t even get back? They’re not marching.”

He and his mate Ken Buss remained close friends for more than 60 years. They exchanged letters, phone calls and regular visits to each other until Ken passed away five years ago at the age of 93. Ian still misses him.

"Oh yes, my word, you had to have a good mate over there," Ian said. “You were friendly with quite a lot of people, but everyone had a good mate, and I did too.”

Ian celebrated his 100th birthday on 19 August 2019 with family and friends, enjoying “a cold stubby and a bit of cheese and bickies” with his children.

Ian celebrating his birthday with his three surviving children, David, Brett and Kym. Their eldest sister Jan died in 1984.

Today, he still considers himself to be fortunate to have survived the war, and credits his long life to “bloody good luck”.

“I was lucky all the way through,” he said.

“My first time being lucky was when I took two steps forward because all my mates went to Burma, to the Burma railway, and only one of them came back, and I was lucky I missed that.

“Then I was lucky because of the five troopships I was on, none of them got bombed, and none of them got torpedoed.

“I didn’t lose any legs or arms, or anything, and it’s just little things like that.

“[War is] an absolute waste; an absolute waste of life. No one has a win; it’s just the other side ran out of supplies before we did. It’s stupid, absolutely stupid, and a terrible waste.

“It’s just luck; straight out luck.”