Service as Citizenship

Current Memorial research estimates that approximately 1,200 Indigenous Australian men attempted to enlist in the First World War. They did so in spite of the military restrictions on their service and the widespread dispossession, discrimination, and inequality many faced in their day-to-day lives.

The willingness of Indigenous men to serve a country that often denied them the rights and privileges freely granted to other Australians did not go unnoticed back home. In the decades following the war, many Indigenous veterans and civilians wrote of their dissatisfaction with their lot in local newspapers, or discussed their misgivings with friendly ears.

The Australian Aboriginal League float in the 1947 May Day procession included several returned service personnel from the Second World War.

Despite having experienced some degree of equality while serving in the First World War, as Indigenous Australian servicemen trickled home from the war – either discharged early after wounding or as part of the mass demobilisation at the end of the conflict – they found themselves returning to a situation largely unchanged from before the war.

Men were once again restricted in where they could live and visit, and who they could socialise with. Many returned to the supervision of missions and stations, where their occupation, marriages, and free time were all carefully managed. Some returned home to find that their children had been taken away while they had been overseas fighting in the war; these children were now wards of the state in the early stage of what would become the Stolen Generations. Communities faced the closure of reserves and the merging of missions, often forcing entire family groups off their traditional land and threatening to separate extended families.

The discrimination and prejudice facing Indigenous Australian veterans and their communities on their return to Australia caused a great deal of resentment for many men.

Indigenous Australian men served alongside non-Indigenous men in the A.I.F. and R.A.N. throughout the First World War. The soldier second from the right in the back row is Private Alfred Coombes, an Indigenous man from Antwerp in Victoria.

A Ngarrindjeri veteran from Raukkan in South Australia reflected that “While I was in the military uniform, I was granted all the privileges one could think of, even going to a hotel and having a glass of beer. Now it is all over … I am practically No-Body.”

In 1935 a man from Cherbourg in Queensland wrote, “I always thought that fighting for our King and country would make me a naturalised British subject and a man with freedom in the country but … they place me under the Act and put me on a settlement like a dog.”

The ongoing inequality facing Indigenous Australian veterans and their communities, exacerbated and highlighted by their recent experience of equality, provided a catalyst for action and activism.

Indigenous Australian activism during the interwar period addressed a number of interlinked concerns, including access to education, freedom to visit pubs and hotels, the protection of Aboriginal land and reserves, and the lack of respect shown to Indigenous Australians by the wider Australian public.

In 1918, a Noongar man from Western Australia wrote to his local member of parliament regarding Aboriginal children not being allowed to attend public schools. In his letter, Kickett argued that “as my people are fighting for our King and Country, Sir, I think they should have the liberty of going to any State school.”

In 1924, frustration with South Australia’s restrictive liquor licensing laws, which prohibited Indigenous Australian people from drinking, spilled over into the Advertiser. An unnamed Aboriginal man complained in a letter to the paper: “While we wore the King’s uniform, on active service abroad, we were allowed to indulge in as much liquor as it was possible for us to consume. Since our return to the land of our birth, and the good old uniform is laid aside, we are again placed under the ‘Blackfellows Act’. Where is the justice of this?”

Condemning the mistreatment of Aboriginal Australians in South Australia, Private John Eustace Bews argued that “there have been many Aborigines who have nobly responded to our Empire’s ‘call to arms’ … we feel humiliated to know that we are still looked upon as a servile cringing race.”

Often, the people writing into newspapers specifically mentioned the death of Indigenous soldiers while fighting in the war, and linked this sacrifice with their campaign for equal rights and recognition.

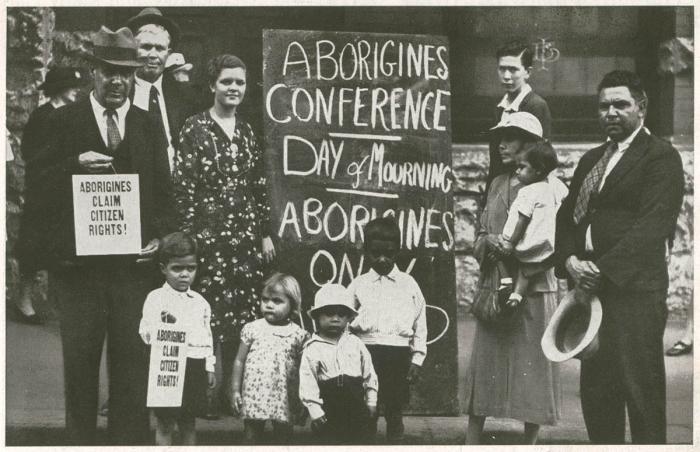

On 26 January 1938, Indigenous Australian protestors held the first Day of Mourning Conference to campaign for greater rights and challenge the discrimination they faced daily. Many attendees had served in the First World War or had family who had.

Credit: Russell Clark, Q 059/9, State Library of New South Wales

A Western Australian Aboriginal man wrote to the Sunday Times in 1921, explaining, “Some of our number took part in the Great War and made the supreme sacrifice, while others have returned to find that they are no nearer getting a fair deal.”

Protesting against the planned closure of the Warangesda Aboriginal Reserve in 1926, a man from the reserve wrote, “During the Great War a number of our boys from Warangesda went overseas … and some did not come back – a nephew of mine amongst them. Do you think, Sir, it was for this they died?”

Despite the hopes of Indigenous Australian servicemen, activists and their communities, the First World War did not change their social or legal status in Australia.

Indigenous Australians were not universally enfranchised until 1962, although veterans were granted voting rights in federal elections in 1949, thanks to activism from Indigenous communities and the Returned Sailors’, Soldiers’ and Airmen’s Imperial League of Australia (today’s RSL).

Activists, their families and their supporters – many of whom were veterans or relatives of those who had died overseas while serving – continued to protest against the denial of rights and recognition well beyond the end of the Second World War.

Voting rights in Commonwealth elections were extended to Indigenous Australians in 1962, with Queensland being the final state to grant voting rights at state level in 1965.

“Our Vote = Our Future” metal badge, National Museum of Australia.

Through their activism, they challenged a political system that sought to keep them disenfranchised and oppressed, and a commemorative narrative that sought to minimise the contribution of members of their communities. In doing so, they refused to accept discrimination and dispossession as thanks for the sacrifice of their loved ones and fellow countrymen, fighting a battle that lasted long beyond the ceasefires and peace treaties that ended the two world wars.

This article is based on the longer piece that appeared in Wartime 104.