A New Set of Wheels – Second World War Bicycle Acquisition for the Australian War Memorial

The standard means of getting about wartime England was the bicycle. With rationing of petrol, the use of motor transport was confined to necessity, so bicycles were used by servicemen and women for personal transportation and getting around Royal Air Force (RAF) bases.

Riding at night in black-out conditions, it was mandatory for cyclists to daub heavy black matt paint on frames and the upper half of front lights, and to carry regulation white patches on mudguards.

RAF members leaving their station on bicycles (image WWII Battle for Britain, Christy Zancanella)

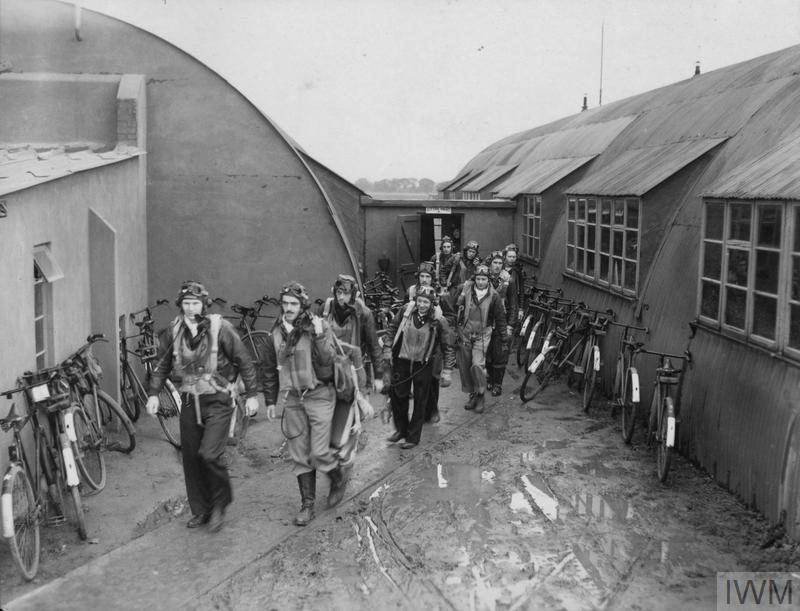

At RAF airfields, buildings and aircraft might be a half mile apart in order to minimise damage in the event of enemy raids or accidents. Because stations were so spread out, the RAF issued its own bikes, which were heavy and often lacked brakes – to enable air and ground crew to get about. Many bases were grim, hastily erected sites. Aircrew lived in prefabricated huts near aircraft dispersal sites, many without electricity or running water. Women’s Auxilliary Air Force (WAAF) staff lived nearby, billeted out with civilians or installed in a Waffery, and relied on their bicycles to get to work – at all times of the day and night, and in all forms of weather.

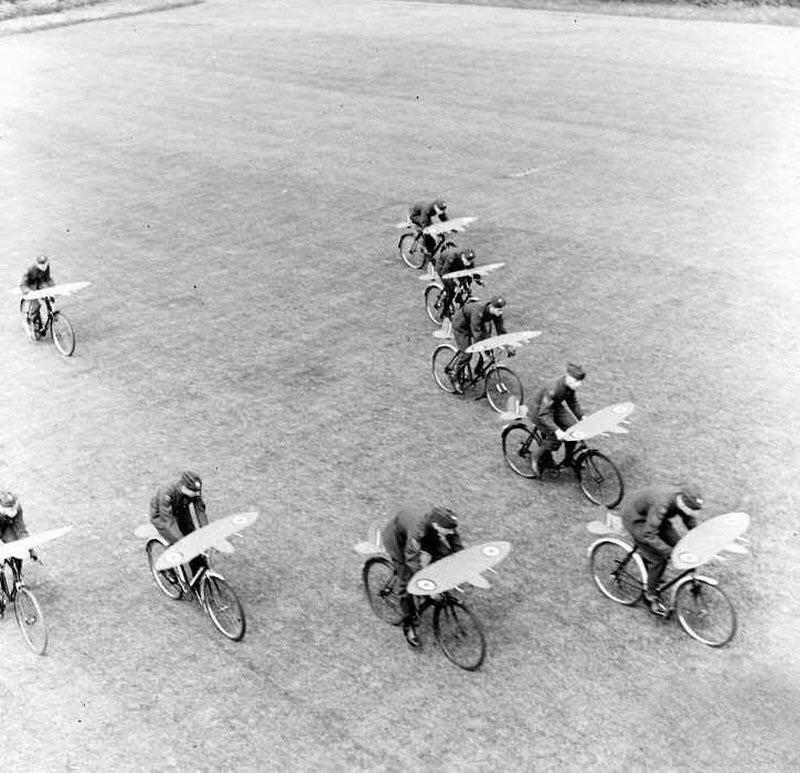

Bicycles were also used to train pilots in formation flying. Wearing radio transmitter sets, pilots cycled around the aerodrome in flying formation, responding to orders to turn until the trainer was satisfied they could maintain disciplined flight. Bikes were even used by some fighter squadrons to simulate intercepts.

Pilots using bicycles to practice flight order (Getty image)

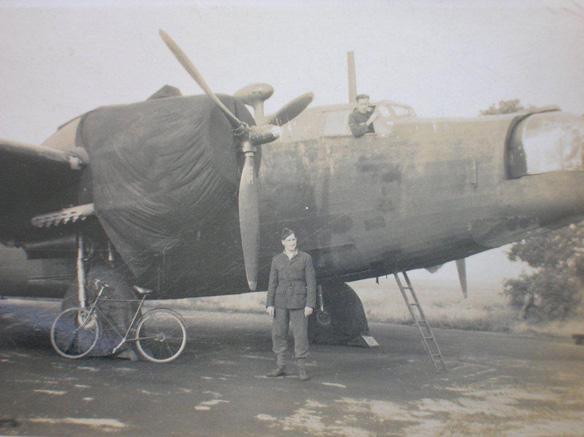

Bike beneath a Vickers Wellington (aircrew remembered)

RAF stations could be made up of 2,000 personnel, only 10 per cent of whom were aircrew. The remainder were ground crew, including armourers and mechanics, members of the WAAF, RAF service police, clerks, drivers, caterers, and medical personnel. Over time RAF stations grew around aerodromes to become small towns, sometimes with entertainment and sporting facilities. Buildings were widely spaced, so the best way to get around was on a bicycle. With many stations located on cold windswept landscapes, temperatures could be icy through the colder months of the year.

“I remember the fog freezing on my battle dress as I bicycled to the flight hut in the mornings.”

Josie Roberts, WAAF

Pilots of the 353rd “Thunderbolts” fighter group leave a briefing, passing bicycles propped against adjacent buildings. IWM FRE 366

Bicycles were issued to crew of all nationalities. As an unnamed American airman of the 303rd Bomb Group put it, “When you’re five miles from the nearest village a bicycle can be a real pal”.

Halifax bomber with crew on bikes (aircrew remembered)

Many men bought their own bikes, costing around three or four pounds, which were more manoeuvrable than those issued by the RAF. Senior Fitter Harry Tickle of No. 460 Squadron recorded, “The old bikes were heavy and often with no brakes or gears – how we returned from the pub in one piece I shall never know. We came home in formation, well oiled and no lights.”

Bikes were a tradeable commodity and almost everyone on an airfield scrounged a cycle from somewhere. Bikes were borrowed from outside pubs, dumped unceremoniously in ditches, or passed on to friends and relatives when an airman failed to return.

Theft was so rampant that the local police constable from Bubwith (a village in Yorkshire near No. 460 Squadron’s base) rode his bicycle to RAF Breighton to complain about bicycles being stolen. When he went outside, his was gone.

A member of No. 463 squadron remembered, “If someone ‘borrowed’ your bike you walked everywhere until it turned up again – usually at the guard house after being picked up as being abandoned.”

RAAF ground crews at RAF Station Waddington cover the fuselage of a Lancaster with greetings to liberated prisoners of war the aircraft will return from Germany after VE Day. UK2856

RAF Museum Curator Andrew Dennis recently donated a Second World War RAF bicycle to the Australian War Memorial. It was air freighted here from England and arrived last week. “I used it on and off for a while, I recall a 25-mile fancy dress bike ride on it, and a pageant at the RAF Museum, when I rode it around the site wearing RAF uniform.”

The new acquisition is painted in wartime blackout scheme (remnants of the original yellow paint are visible), has the white blackout marking on the rear mudguard, red, white and blue bands, and the text “NW667”, referring to RAF station North Weald, an 11 Group Fighter Command airfield in the front line of the Battle of Britain. The words “Ding Dong” are emblazoned on the cross bar and an RAF stamp appears on the fork above the front wheel.

The Memorial’s bicycle at a RAF Museum Open Day (Andrew Dennis)

Though they transported countless thousands of merry-making air and ground crew to singsongs and dances at halls and pubs, there is a poignant side to the wartime RAF bicycle:

“Walking distances were great on a Squadron. Hut to central ablutions, to mess, to flight hut, to briefing, to NAAFI … I was lucky in that I inherited a bicycle sent from another Squadron, on the request of a father in Sydney, whose son was missing. That boy’s father knew my father and wanted me to have his son’s bike.”

Flying Officer John Musgrove, Bomb Aimer 576 Squadron RAF

In official correspondence from RAAF Casualty Section, thousands of letters to next of kin include messages such as this letter to the parents of Flight Sergeant John Keys No. 466 Squadron, whose Halifax was shot down on 10 April 1944 with the loss of all seven crew: “[We] deeply regret to inform you that all efforts to trace your son have proved unavailing and it is feared that all hope of finding him alive must be abandoned … I have to advise that a bicycle owned by him is held at his former unit.”

When an airman failed to return, a committee of officers, known as a “Standing Committee of Adjustment”, at the RAF station gathered the missing man’s personal effects and forwarded them to a central RAF depository. Bicycles were held until death was confirmed or for three months from the date the airman became missing. Families were advised, “In view of the difficulty experiences in storing articles of this nature, and of the fact that it is not practicable to return them to Australia, his bicycle will be sold and the proceeds held on his behalf.”

The addition of a genuine RAF bicycle to the Memorial’s National Collection enriches our understanding of life on a base during the Second World War.

RAF fighter pilot. IWM CH 5592

An airman of the 322nd Bomb Group with a bicycle in front of Nissen Huts. IWM FRE 1464