The Siege of Elands River

One battle of the South African War 1899-1902 typifies all the qualities that Australia has come to interpret as synonymous with the Anzac legend, but it occurred almost fifteen years before Australian soldiers ever landed at Gallipoli. This was the Siege of Elands River, a twelve day siege of a supply depot defended by soldiers from five of the six Australian colonies.

One item in the Australian War Memorial’s collection relating to this battle is the headstone that was placed over the graves of Sergeant-Major James Mitchell and Troopers James Daniel Duff, John Waddell and James Edwin Walker, all of the New South Wales Bushmen, killed at Elands River.

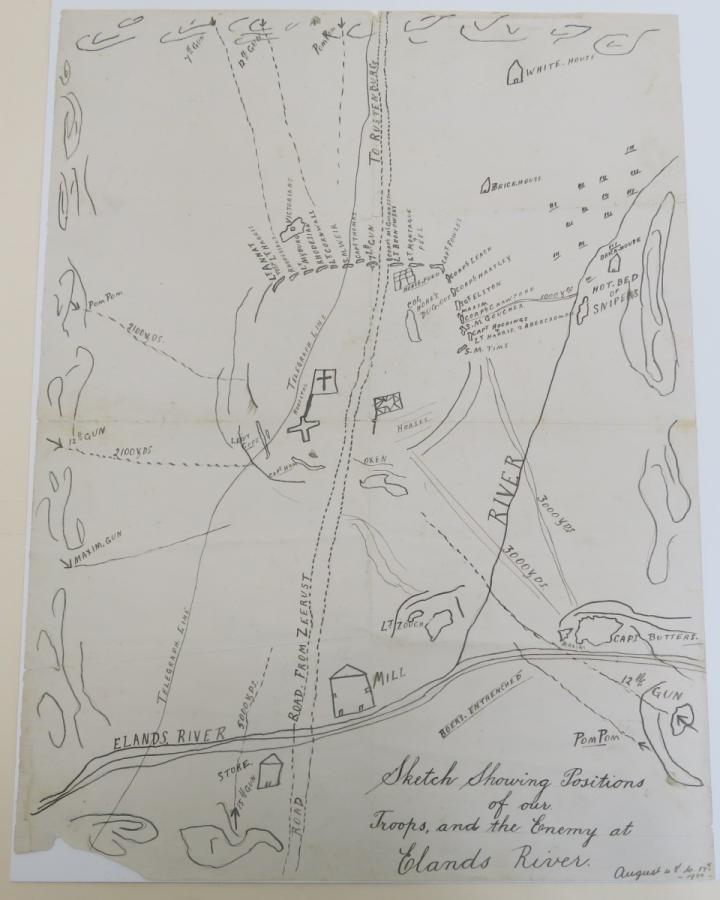

The Siege of Elands River began on the 4th of August 1900 when over 2500 Boer commandos under the command of General Koos de la Rey surrounded the camp. The Boers had at their disposal five modern artillery pieces as well as three 1pdr ‘pom-pom’ guns and two Maxim machine guns. The men who were besieged within the compound numbered about 500, almost 300 of which were Australian, 200 Rhodesians and a few British and Canadians, with some civilians and native porters sheltering within the perimeter. Under the overall command of British Lieutenant Colonel Charles Hore, their only heavy weapons were, two machine guns and old muzzle loading 7pdr gun.

The camp was a supply depot, which held supplies estimated at around £100,000, including 1500 head of livestock and horses. It was an appealing target for the undersupplied Boer forces.

With only small warning, the defenders began construction of defensive trenches as far out from the camp as possible. A hospital was constructed out of biscuit boxes and a Red Cross flag was raised over it. At the time of the initial attack the trenches were not able to provide adequate protection to the men and were made mostly of rocks piled up into a defensive wall.

The Boers began their attack with an artillery and pom-pom gun barrage. In a trench commanded by Captain James Francis Thomas, who would later gain fame for defending Harry ‘Breaker’ Morant and Peter Handcock during their court martial, the first Australian fatalities would occur. Trooper John Waddell was hit in the chest by a pom-pom shell, he died within a few minutes. Only a couple of minutes later James Duff became the second Australian to be killed during the battle, also receiving a pom-pom shell to the chest, he was killed instantly. Sergeant-Major James Mitchell was in a nearby trench when he was wounded in the leg. He moved to Captain Thomas’ trench where his wound was bandaged, the Boer fire was too intense to contemplate moving him to the hospital so he remained at the front lines.

Studio portrait of Trooper John Waddell, killed on the first day of the siege.

During that first day the Boers fired an estimated 1700 shells into the besieged camp. Five of the defenders were killed, two from Australia, two Rhodesians and a native worker. Most of the 1500 animals were either killed or wounded by the shells. For those poor animals that were wounded, little could be done, men who tried to assist them or put them down were targets for Boer snipers.

That night the five men who were killed were buried in one large grave, there was no time for a memorial service; this would have to wait till the end of the siege.

On the second day a relief force under Major-General Frederick Carrington was seen in the distant and much of the Boer force was moved to meet this new threat. General Carrington’s column fell back after a brief skirmish with the Boers. Carrington mistakenly told his superior Lord Roberts VC that the camp had fallen and as a result a second, larger, relief force under General Baden-Powell (The hero of Mafeking) turned away from the camp.

On the 6th the New South Wales Bushmen suffered their third fatality, Trooper James Walker. We don’t know how he was killed, but we do know that he was buried that night next to Troopers Duff and Waddell.

On the 8th General de la Rey sent an offer of honourable surrender to the besieged. This offer was dismissed out of hand by Rhodesian Captain Butters who was first to receive the message.

Also on the 8th a shell hit the hospital. Sergeant-Major Mitchell, who was having his leg treated at the time, was hit again in the leg. This time the wound was severe, and required amputation. By the 11th of August he was showing signs of infection and fever had set in. He passed away the following day and was buried next to his fellow New South Wales Bushmen in the small cemetery.

On the 13th a runner reached the British with a message that proved that the camp was still holding out. Upon hearing that the men were still under siege at Elands River General Kitchener, without waiting for orders, immediately moved two brigades to go the relief of the camp. They arrived on the 16th to break the siege.

Captain Albert Duka, a doctor from Queensland who had treated all of the wounded listed 73 casualties, including 16 killed. Of the 16 killed, 8 were Australian, 4 were Rhodesian and 4 were natives. For his service to the wounded Duka would later be awarded the Distinguished Service Order.

The men that were killed during the siege were buried in an improvised cemetery within the perimeter of the camp. They were buried quietly at night, without proper funeral services. After the siege was lifted a large funeral was held for all those that were killed, names were etched into large pieces of slate to serve as headstones. The largest piece of slate was used to mark the graves of the four men from New South Wales that were killed. White rocks from the outlying hills were brought down and placed on the graves.

Photograph of the headstone for the New South Wales Bushmen, taken shortly after the battle.

It is commonly thought that all four men were buried in a mass grave as they were only given the one grave marker. This seems unlikely as we know that they were buried on different nights and it is very unlikely that they would have dug up the same grave.

After the war the original slate headstones were replaced with individual crosses when the bodies were reinterred at the Swartruggens Cemetery. The slate headstones were kept in the cemetery. The Gravestone for the four New South Wales Bushmen was sitting in the cemetery, broken into two pieces, until it was rediscovered in 1966 by an Australian author. Ten years later after much negotiating with the South African Government, the Australian Government was able to ship the two pieces of the gravestone to Australia. It arrived in 1977, was presented to the Australian War Memorial where it has been proudly displayed ever since.