'We volunteered and did what was expected of us'

Terry Colhoun in Melbourne in July 1943, age 18. Photo: Courtesy Terry Colhoun

Terry Colhoun was 14 years old when the Second World War broke out in September 1939.

A teenager growing up in Melbourne, he knew life was about to change forever.

“I was in bed at home in Surrey Hills,” he said.

“I was reading a book, and Mum and Dad were listening to the radio, or what we used to call the wireless in those days.

“Mum came in at about nine o’clock and said, ‘Mr Menzies has been on the air, and Australia is now at war with Germany.’

“I was just three months short of my 15th birthday, and I suddenly became a scared boy, who was near enough to being grown up, to see military service ahead of me.

“I was pretty upset, and I cried a bit that night, I must admit; not that I was a person who normally cried much. But I certainly did that night.”

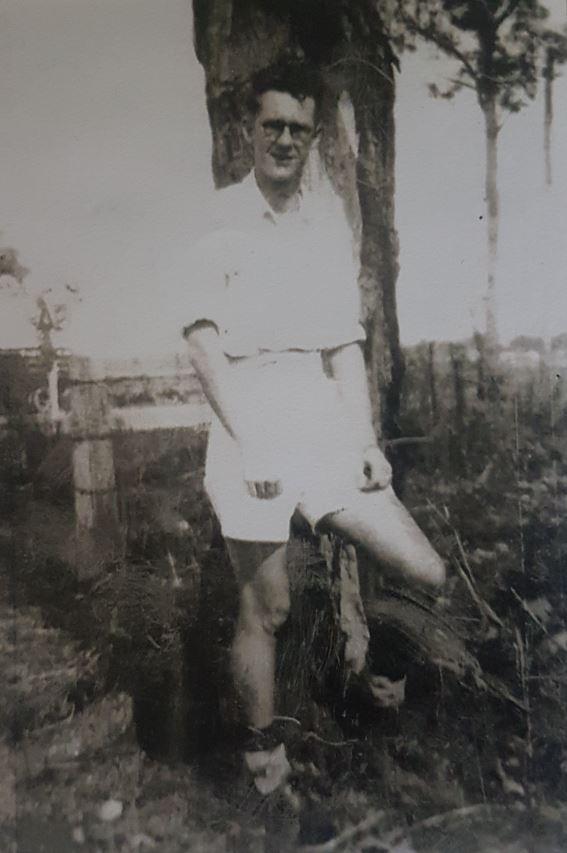

Terry Colhoun at RAAF Station Darwin in 1945, age 20. Photo: Courtesy Terry Colhoun

The eldest of four brothers, Terry worried about the war and his place in it. He lost interest in school and left to help his parents make ends meet.

“I was working at the Myer Emporium at the time, and the day after my 17th birthday, the bombing of Pearl Harbor happened,” he said.

“I felt it deeply. I was just one year away from being conscripted, and I had to decide what I would do about that.

“I was a fairly timid kid, certainly not an aggressive boy, and I thought about it a lot.

“Without telling my parents, I walked up to Russell Street to the RAAF recruiting depot, and said, ‘I don’t have much to offer, but I believe I’m going to be called up sooner or later, and I’d prefer to serve in the air force, could we talk about what I could do?’

“After I made this rather adventurous move, I had to go and tell Mum and Dad, didn’t I? They had, of course, been even more worried than I was. They knew there was no way I would dodge military service, and they were very relieved, I think, when I went home and told them I had made a decision.

“I had to wait until the following year, until I was 18, but the air force said they would call me up, and they did.

“I also got a call-up – a conscription notice – from the army, but I took it to the air force, and they said, ‘Take no notice of it son, you’re ours.’”

RAAF Station Darwin Airman's mess. Photo: Courtesy Terry Colhoun

When he turned 18, Terry reported to the recruiting centre again and was sworn in.

“I think Mum was rather proud to walk down the street with her boy in an air force uniform,” he said. “This sweet young thing of 18, who had barely been kissed.”

He was posted to Shepparton in north-east Victoria for training, where he marched around the showgrounds, carrying a pretend rifle – made from hardwood to resemble a .303 rifle – over his shoulder. The only time Terry saw a real weapon was at the rifle range where he was taught how to pull it apart, clean it, and put it back together again.

He went on to serve as a clerk in the orderly room at No. 1 Signals Training School at Point Cook, before being posted to No. 1 Embarkation Depot, a makeshift depot set up at the Melbourne Cricket Ground, and then to 79 Wing Headquarters at Batchelor in the Northern Territory.

“At that stage, we didn’t know where we were going,” he said.

“We were put on a troop train, and we left in the dark … I awoke the next morning in a place called Terowie, which was a railway junction in northern South Australia.

“We were told we would be travelling north on the Ghan [a passenger train that travelled between Port Augusta and Alice Springs]. But there were no luxuries in those days. It was just old wooden carriages, and the air-conditioning was open the window and get a face full of soot.

A damaged building in Darwin. Photo: Courtesy Terry Colhoun

The damaged Bank of NSW in Darwin. Photo: Courtesy Terry Colhoun

“It was all men, sitting up in old second class seats, and we did that for about three or four days.

“The rails were buckled by the heat, and we joked that the train ran on square wheels.

“Bully beef and hard Army biscuits featured. And God, they were hard, those Army biscuits. You could break your teeth trying to eat them.

"The best use I ever found for them was to pour boiling water over them and use them as porridge, for which they were very good.

“When we got to Alice Springs, we were put into army buses and taken to a place where we could get a shower and some cooked food, but there were no tents or anything, and I remember setting out my rubber ground sheet and sleeping on the ground, fully clothed, with my two grey army blankets wrapped around me, and using my air force kit bag as a pillow.

“It was the coldest night I’ve ever had.

“The next day we were piled into army trucks, just sitting on the floor, until we reached Larrimah, the southern terminal of what was the old Northern Australian Railway, to take us up to where we were going.

“In my case it was Batchelor, which was just a place hacked out of the bush, about 100 km south of Darwin.

A damaged house in Darwin. Photo: Courtesy Terry Colhoun

“There was quite a big landing strip there, and I was told I was going to work in the Operations Room of 79 Wing Headquarters.”

At the time, 79 Wing controlled two-engined aircraft, flying from squadrons located at Batchelor, Coomalie, Hughes, and Gove airfields.

As an acting corporal, Terry was responsible for typing up operational instructions, writing up records and reports, and encoding and decoding messages between the control room and aircraft that were in flight.

More than once he had the painful duty of decoding messages from aircraft reporting the loss of a plane and its crew.

“There were aircraft coming and going at all times of the day and night,” he said.

“You’d be working all through the day, and then all through the night, and you’d come off at seven o’clock in the morning, and rush to have a shower.

“If it was the wet season, you probably had prickly heat from top to toe, and then you’d get to the airmen’s mess, and the meal was appalling.

"I can remember on more than one occasion fronting up to weevilly rice and half-cooked prunes, followed by what they called scrambled egg, which was made from some powder concoction that smelt and tasted like brown paper.”

He has fond memories of sneaking over to No 18 Squadron to enjoy a smorgasbord of food.

“No 18 was a Dutch squadron which had escaped from the Netherlands East Indies before the Japanese moved in, and re-formed in Canberra as part of the RAAF,” he said. “It proudly retained an NEI identity, and one day I decided to get some relief from our RAAF diet by hitching a ride to their camp for a marvellous Reischstaffel lunch… The curries were as hot as hell, but it was worth it.”

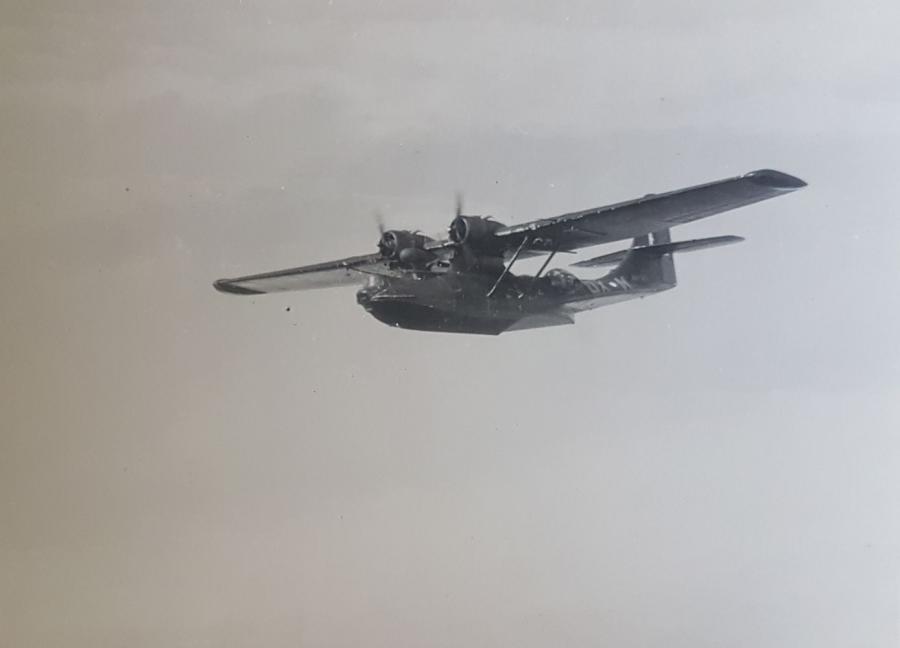

A Catalina from 43 Squadron. Photo: Courtesy Terry Colhoun

The Darwin hospital. Photo: Courtesy Terry Colhoun

In February 1945, Terry was posted to Truscott to fill in for an operations clerk who had been sent to Darwin for surgery.

“It was an improvised landing strip on the Western Australian coast north of Broome near the Drysdale River,” he said.

“I flew over on an operational flight and was allowed to sit in the co-pilot’s seat, which was a great thrill for a kid of my age.”

He returned to Darwin on board an old Avro Anson.

“There were another airman and myself, and three padres,” he said. “But as we approached Darwin we ran into a tropical storm.

“The wings were flapping up and down, and I said to the corporal, ‘I hope the padres are saying a few prayers for us.’

“Then when we got to Darwin Harbour, the plane dropped down under the clouds.

"We were skimming over the water, coming in to land, and I still have this memory of seeing a rowing boat down below us.

"It was probably some off duty soldiers fishing for barramundi or something, and I remember them ducking as we went over because they thought we were going to give them a haircut.”

A B-24 Liberator Bomber over Darwin. Photo: Courtesy Terry Colhoun

Mindil Beach, Darwin. Photo: Courtesy Terry Colhoun

Terry flew to Brisbane on a Liberator bomber on the 15th of August, the day the war ended.

“As we left Darwin, about 8 o'clock that night, I looked down at Mindil Beach,” he said.

“The whole beach was covered with bonfires and things, where thankful servicemen and servicewomen were celebrating.

“There were no seats on the plane, and we passengers sat on an uncomfortable non-slip floor as a cold wind blew across us ... but to hell with that. I didn’t care. I was going home.”

Reunited with his parents on the platform at Spencer Street Station in Melbourne, Terry was later posted to the Airmen’s Records section, where he was responsible for returning airmen's flying log books to their owners or next-of-kin.

“The flying logs were mostly of airmen who had died in action, and I had row after row of them,” he said.

“I read about amazing flights and deeds of heroism; much better than the Biggles stories I had read as a boy, and much sadder, most of them having been written by men who were no longer alive.

“They were real heroes – highly decorated – and to read about them going out over Germany and places like that was a real privilege.

“And that was the last job I had.

“I was invited to stay on, but all I wanted was to get back to civilian life.

“When you join up as a boy at 18 – and you still are a boy at 18, even if you think you are all grown up – that’s a crucial time of your life.

“To me, the thing was to get out, and start a career, and hopefully find somebody you’d wish to marry with whom you could have a family.

“At the end of the war, we were not wanting parades, we were not wanting big speeches, we just wanted to have a job, and to start a civilian life, the civilian life that we’d not had.”

Terry Colhoun AM at the Australian War Memorial for the 2021 Anzac Day National Ceremony.

After the war, Terry became a successful broadcaster, working in commercial radio, and for the ABC in Gippsland, Newcastle, Canberra, and New York.

He joined the Citizen Air Force during the Cold War, and conducted oral history interviews for the Australian War Memorial as part of the Australia Japan Research Project. He was also the Anzac Day Parade commentator in Canberra from 1997 to 1999, and was Master of Ceremonies for the Memorial’s Anzac Day Dawn Service from 1997 to 2006.

He was appointed a Member of the Order of Australia for service to music and radio broadcasting and to the community and was awarded the Japanese Oder of the Rising Sun with Gold Rays and Rosette for service to Australia-Japan understanding.

“I don’t regard myself as one of the heroes,” he said. “I was just one of the ordinary people who did ordinary jobs to enable certain people to be heroes.

“I’m proud of what I did, and I’m proud of the fact I made my choice, and that I’ve survived, right up until the present time.

“But when I go into the Memorial, I become quite emotional, because war is a terrible thing.

“It produces the best in certain people, but it produces the worst in others.

“Having lived through the Second World War, from a teenager into young adulthood, and having lost a brother as a result of terrible suffering from his service in Japan after the war … it’s personal.

“My story is that of an ordinary young Australian who, like thousands of others, volunteered his life in defence of his country, and served without distinction.

“People did what they thought they should do … and we’ve got to remember these people, whether we knew them or not.

“I am thankful that I survived the war and can tell younger Australians that not every serviceman and servicewoman was a hero, but we volunteered and did what was expected of us.”

Terry Colhoun AM at the Australian War Memorial for the 2021 Anzac Day National Ceremony.