The bugle and the breakout

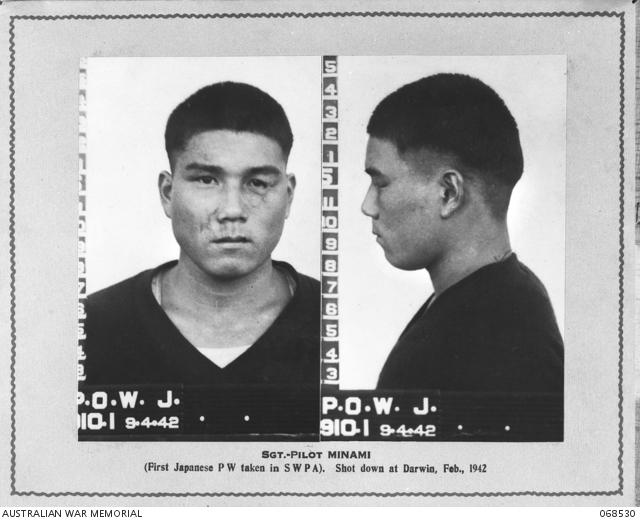

Sergeant Hajime Toyoshima was Australia's first Japanese prisoner of war.

Just before 2 am on Saturday, 5 August 1944, Japanese fighter pilot Hajime Toyoshima sounded the bugle that signalled the beginning of the Cowra breakout.

Today, the bugle is part of the national collection at the Australian War Memorial, a poignant reminder of the largest escape attempt from a prisoner-of-war camp in Australia – and a reminder of the lives that were lost.

“We don’t actually know a lot about the provenance of the bugle itself,” said Dr Kerry Neale, a curator at the Australian War Memorial.

“It was made by Boosey and Hawkes Ltd of London in the 1930s, but the actual origins of the bugle, and how it came to be in Toyoshima’s possession, are a bit of a mystery.

“What we do know is that Toyoshima used it to signal the start of the breakout, so it has a really significant place in Australia’s military history.

“The camp commander Major Edward Timms, who served on Gallipoli and had seen the devastation of the First World War, he recovered the bugle after the breakout, took it back to his home in Sydney and hung it in his sitting room. There it remained for many years, until his widow donated it to the Memorial after his passing in 1978.

“The breakout was the one and only time that an escape attempt of this scale occurred on Australian soil, and it’s a very big part of Cowra’s history and the town’s ongoing relationship with the Japanese community, and the very beautiful reconciliation and friendship that exist between them today.”

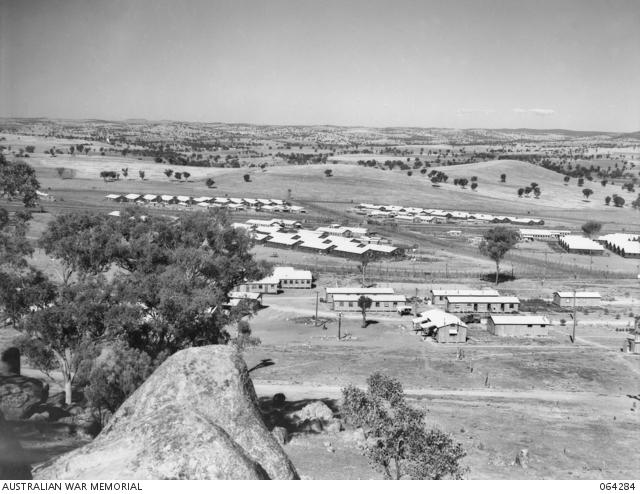

Located three kilometres north-east of the town, the Cowra prisoner-of-war camp was originally built in 1941 for Italian prisoners of war who had been captured in North Africa.

“The first Japanese prisoners arrived at Cowra in January 1943,” Dr Neale said.

“But the Japanese military ethos was not to be taken prisoner. This meant it was seen as shameful; you should fight to the very end; so the very idea of being a prisoner of war was something that didn’t sit well with a lot of the prisoners in the camp.”

Like many Japanese prisoners, Toyoshima had given a false name to avoid the shame of being captured from impacting on his family.

“Toyoshima was the pilot of a Japanese Mitsubishi Zero,” Dr Neale said.

“His plane was damaged in the first air raid over Darwin on 19 February 1942 and he made a crash landing on Melville Island.

“It was there that he was approached and apprehended by a Tiwi man, Matthias Ulungura, from the Snake Bay settlement.

“Ulungura disarmed him before taking him to Bathurst Island, where he handed Toyoshima over to the engineers who were working there.

“There is an anecdotal story that Ulungura used a stick pointing into his prisoner’s back to mimic a gun, because they didn’t have weapons of that sort.

“The man they handed him over to – Sergeant Leslie Powell of the 23 Field Company, Royal Australian Engineers – had been sent to maintain demolition installations on the island and was actually unarmed as well, so he used Toyoshima’s own service pistol to escort him into captivity.”

Sergeant Hajime Toyoshima with Sergeant Leslie J. Powell. The pistol that Powell is holding is Toyoshima's service pistol.

Toyoshima became the first Japanese prisoner of war to be taken by Australians, and was sent to Cowra, where he was known as Tadao Minami.

“Relations between the Japanese prisoners and their guards were poor,” Dr Neale said. “But the prisoners had made no firm plans for a mass breakout until early August, when they were made aware of plans to separate inmates, relocating all Japanese prisoners below the rank of Lance Corporal to a camp at Hay in western New South Wales.”

In Japanese military culture at the time, NCOs and privates had a relationship often likened to older and younger brothers. To separate them was considered unthinkable.

“Their frustrations compounded over time, but it was when they heard that they were going to be moved that they resolved to act,” Dr Neale said.

“They knew they wouldn’t actually succeed and that they would probably die during the night, but it was the attempt that was important. They were desperate to lose the stigma of being a prisoner and were willing to take whatever measures were necessary.”

When Toyoshima sounded the bugle in the early hours of 5 August 1944, prisoners armed with knives and improvised clubs rushed from their huts and began breaking through the wire fences.

“Though many Australian guards had heard rumours of an attempted escape, none were prepared for the intensity and ferocity of the seemingly suicidal charges of the Japanese prisoners,” Dr Neale said.

“They had gathered lots of blankets and heavy clothing that they could wrap around themselves so that they could charge the barbed wire fences. And while some crawled under the wire most actually threw themselves on the wire for others to climb over.”

Toyoshima's aircraft after he crash landed on Melville island. It was the first intact Mitsubishi Zero aircraft to be captured.

The surprised guards rushed to their posts as prisoners set fire to the camp buildings and the sentries opened fire.

“Privates Ben Hardy and Ralph Jones dragged their coats on over their pyjamas and pushed their way through the rioting prisoners to a machine-gun,” Dr Neale said. “They continued to fire their Vickers gun until the very end.”

Hardy’s final actions were to render the gun unusable, preventing it from falling into the hands of the Japanese. He was clubbed to death, and Jones was fatally stabbed by one of the prisoners. Both men were posthumously awarded the George Cross for their actions.

Two more guards were killed during the breakout. Private Charles Henry Shepherd was stabbed in the chest and killed by a prisoner as he emerged from the guardroom; and Lieutenant Harry Doncaster, 19th Australian Infantry Training Battalion, was killed trying to catch a group of escapees.

A member of the local Volunteer Defence Corp, Thomas Hancock, also died as a result of an accident during the search for escaped prisoners.

In the following nine days, 334 prisoners were retaken. In all, 234 Japanese were killed and 108 wounded.

“Among the dead was Toyoshima, the man who had blown the bugle,” Dr Neale said. “He committed suicide in a ditch just outside the perimeter wire.”

The Japanese dead were buried in a plot next to the Australian War Cemetery in Cowra – the only Japanese military cemetery in the world outside Japan.

The surviving prisoners were split up and moved to camps at Hay and at Murchison in Victoria, where they stayed until they were repatriated to Japan after the war.

Army Sergeant Major Akira Kanazawa was one of the ringleaders of the breakout. He had stressed that, while Australian Army soldiers were to be attacked, no prisoner was to harm or interfere with civilians in any way.

Kanazawa’s orders were carried out to the letter. In stark contrast to the desperate brutality the escapees used against Australian soldiers, no civilians were harmed during the breakout.

16-year-old Bruce Weir and his father went out into their fields on Saturday morning to move some sheep. They were approached by three Japanese escapees who indicated that they were hungry. Taking them to the house, Bruce’s mother May gave the men tea and scones until the authorities arrived and recaptured the prisoners.

In a certain sense, reconciliation began with the actions of May Weir.

On the 20th anniversary of the breakout, in 1964, the Ambassador of Japan and the head of the Australian War Graves Commission opened the military cemetery in Cowra, which has become a centre of commemoration and remembrance for both Japanese and Australians.

“In many ways, the cemetery is a place which links the violence of the past with the restoration of the present,” Dr Neale said. “The Japanese gardens and the peace bell are symbols of hope and harmony set against the reality of the violence of the past.”

A Last Post Ceremony commemorating the life of Private Charles Henry Shepherd will be held on 5 August 2024 to mark the 80th anniversary of the Cowra breakout.