The curious case of the Emden Bell

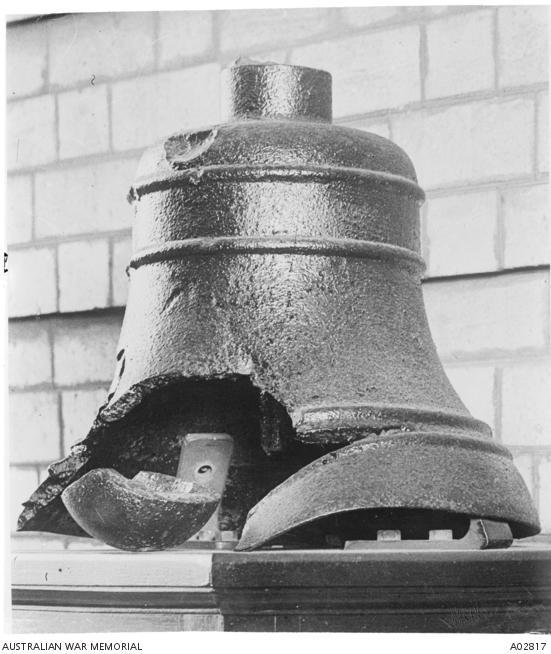

The damaged bell of the German cruiser Emden. Photo: The Sydney Morning Herald

In April 1934, a small elderly lady hurried into the temporary Australian War Memorial exhibition in Sydney.

Approaching the nearest attendant, she asked breathlessly: “Will you please show me where the Emden Bell is? I’d like to see it before it is stolen again.”

The tale of the Emden Bell is one of the more unusual stories from the Memorial’s collection.

Recovered from the wreck of the first enemy ship sunk by the Royal Australian Navy during the First World War, the bell was twice stolen and recovered in high-profile cases that captured the public imagination and made newspaper headlines around the country.

The bell came from SMS Emden, a German cruiser that had been stalking shipping routes across the Indian Ocean and south-east Asia from August 1914, wreaking havoc on Allied shipping.

Emden became the scourge of the Allied navies, capturing or sinking 21 vessels before being attacked, driven aground and destroyed by HMAS Sydney at the Cocos (Keeling) Islands on 9 November 1914.

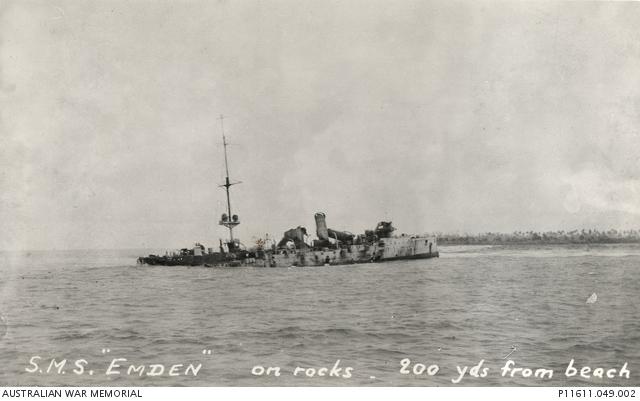

The last of the German raider SMS Emden at Cocos Island. A life-boat from the Australian cruiser HMAS Sydney is on its way to the Emden.

The wreckage of the German cruiser Emden as she appeared about three months after being driven ashore under heavy bombardment from HMAS Sydney.

The ship’s bell was one of many relics removed from the wreck by the Royal Australian Navy and retained as a war trophy.

It’s an object Memorial Curator Dianne Rutherford knows well.

“While the battle between SMS Emden and HMAS Sydney is one of the more significant actions in Australian military history, it is the story that came after – of a battle damaged bell, a determined German immigrant, and a tenacious director – that is perhaps one of the more interesting aspects of the story,” Rutherford said. “It’s a bit of a true crime, cracking detective yarn, and is a very interesting part of the Memorial’s history.”

The bell had been cast in the 19th century for a wooden ship, but was later presented by the German city of Emden to Emden when she was commissioned in 1909.

It was displayed at the Australian naval base on Garden Island in Sydney from 1917 until it was stolen in a daring raid in 1932. It had been bolted to a stand in the entrance porch of the main office, but was discovered missing on 12 August. It was eventually found buried in the Domain in February 1933 and donated to the Memorial for safekeeping.

Relics removed from the SMS Emden after its battle with HMAS Sydney in the Cocos (Keeling) Islands on 09 November 1914. The battle damaged ship's bell is at the front.

Emden

Cocos Islands, Indian Ocean. November 1914. The wrecked German cruiser Emden lying on the reef at North Keeling Island following its engagement with HMAS Sydney.

With the rise of the Nazi Party in Germany, the Memorial feared the bell could become a target for German nationalists, and wanted to make sure it was secure.

It was displayed as part of the Memorial’s temporary exhibition in Sydney, secured to a heavy plinth by a thick steel cable, which was bolted to the ground.

This did not stop it being stolen a second time. In late April 1933, two months after it was recovered, it disappeared again.

One suspect for the theft was Charles Kaolmel, a 30-year-old German immigrant, who had arrived in Australia in the 1920s.

Kaolmel had been involved in the earlier recovery of the bell. He claimed he bought it from an unknown man for £150 and planned to sell it in Germany, but panicked when he discovered it was stolen. He said he then buried the bell in a garden bed in the Domain, about 18 metres from the Ladies Swimming Baths, fearing he would be charged with the crime.

In reality, Kaolmel had come across references to the bell on Garden Island and it stuck with him. He later saw it after attending an auction sale on the island – the only opportunity for the general public to gain access – and realised it would be easy to steal.

Charles Kaolmel, a 30-year-old German immigrant, arrived in Australia in the 1920s.

A few nights later he took a motor launch to the island, stopping the engine on approach and drifting to the jetty near the main office. He located the bell, undid the bolts, and carried it to his boat before returning to anchorage at Woolloomooloo. He kept the bell covered in his boat until the next day when he took it to a shack at the unemployment settlement at the Domain. The next night he buried it.

“Whether there was some patriotism involved or whether it was just for financial reasons we don’t know,” Rutherford said. “But the second time was more personal; he was angry about how he was treated during the first investigation.”

For the second theft, Kaolmel used a pair of pliers to cut the wire fastening the bell to its pedestal at the exhibition in Sydney before placing a bag over the bell and carrying it to the fire escape, and then putting it in a truck.

“The first theft was a bit more off the cuff, but the one from the Memorial exhibition was carefully planned,” Rutherford said.

“You’ve got attendants; you’ve got staff; you’ve got visitors; so he really plotted that one out and went to a lot of effort.

“He purchased a truck to transport it, and wore a leather apron under his coat so that he could pretend he was a tradesman.

“There was an exit from the men’s toilets, and he propped that open, and pretended to be a staff member, and carried it through that door, and put it in a box in the truck, and had it shipped down to Melbourne using one of his aliases.”

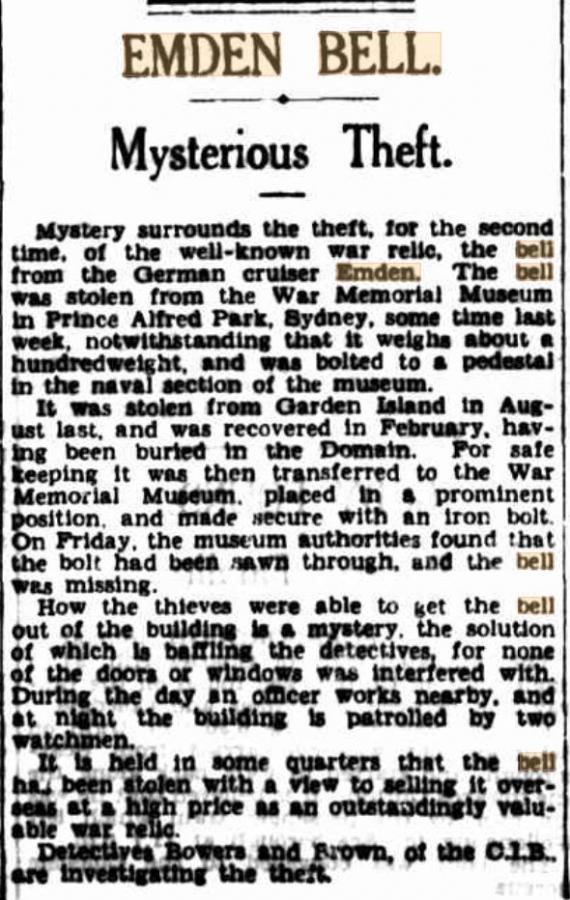

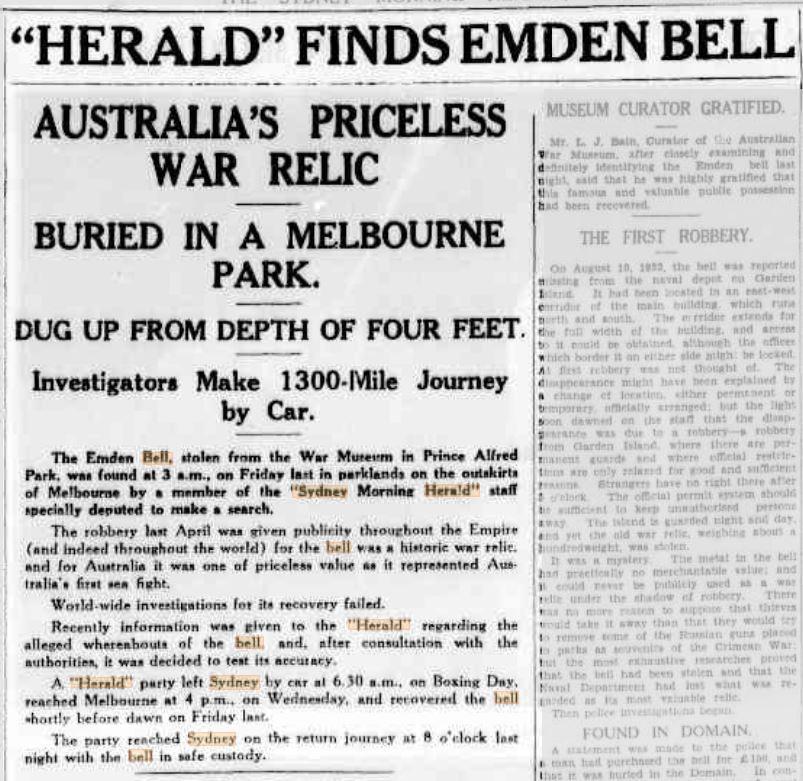

An article reporting on the theft in The Sydney Morning Herald on 1 May 1933.

The theft was discovered within a day, but over the following months, the police investigation failed to find the culprit. Memorial Director John Treloar, a First World War veteran who headed the Australian War Records Section and played an important role in establishing the Memorial, became heavily involved in the case.

“There was a fair bit of public interest, and Treloar wanted to make sure it was found,” Rutherford said.

“Because of the rise of German nationalism at the time, he was concerned about someone stealing it and sending it back to Germany, and he thought they had done a pretty good job in securing it, but Kaolmel just bought a very sturdy bolt cutter.

“Treloar wasn’t impressed. He was a man of detail, and the police didn’t seem to be making any headway, so he started his own investigations.

“He had been writing to people asking them to donate objects to what would become the Australian War Memorial in Canberra and he was concerned about the Memorial’s good name. He wanted people to be confident that objects would be looked after, so the bell going missing the way it did was not a good look, and that’s part of the reason he went as hard as he did in trying to find it.”

John Treloar during the Second World War. He became one of the main investigators examining the case.

Using the Memorial’s and his own money, Treloar spent almost £550 (around $56,000 today) to finance the investigation and was one of the main investigators examining the case.

He turned to the Commonwealth Investigation Branch and Robert Wake from the Naval Intelligence Office for help as Wake had worked on the earlier case. Rumours soon spread that the bell was on its way to America or Germany, but investigators felt it was still in Australia.

Various suspects were investigated, and an unsuccessful attempt was made to locate Charles Kaolmel based on his role in the first theft.

“When they noticed the bell was gone, Charles was one of the suspects, but they couldn’t find him,” Rutherford said.

By August, a man named Charles King was the main suspect.

“They kept an eye on the ports in Melbourne and Sydney, and that’s how they eventually found him,” Rutherford said. “They had been watching German shipping, and in October saw a man in Port Melbourne vaguely matching King’s description.”

John Treloar, right, would become the commanding officer of the Australian War Records Section.

The man told investigators that he was Charles Watts and that he lived with his wife Constance at 170 Capel Street in North Melbourne. He said his father was a Russian named Wattski to explain his accent.

“It took them a while to work out that Watts and Kaolmel were one and the same,” Rutherford said.

“He only looked a bit like the description of King, and they didn’t want to be accused of unlawful detaining Watts, so he was allowed to leave, but there were plans to follow up the detail.

“Investigators visited Capel Street and tried to discreetly interview Constance, but she realised who they were and twigged to what was going on.

“She went to the Shrine of Remembrance in Melbourne where he was working in the latter stages of its construction and warned him that people were after him and tipped him off.

“She didn’t believe he’d stolen the bell and she wanted him to come home. He asked … her to collect his best suit and take money from their bank account and to meet him with them. He then changed and left Melbourne.”

Charles Kaolmel used a number of different aliases, including Charles Watts and Charles King.

An informal portrait of Charles Kaolmel's wife Constance.

At about the same time, Treloar and the authorities put the pieces together and realised that Watts, King and Kaolmel were the same man. That afternoon they visited the site of the Shrine in Melbourne only to discover that Charles had already left. When Constance returned home that evening with a suitcase, they questioned her and then put a watch on her.

Charles made his way back to Sydney, going into hiding for several weeks until he was arrested on 17 November 1933, sitting on a bench in Hyde Park.

While Kaolmel maintained he had not stolen the bell, which had not yet been recovered, he was charged with both thefts, found guilty and sentenced to six months’ imprisonment.

After months of speculation as to its location, including stories that it had been shipped to America or Germany, the bell was finally located on 29 December 1933.

Kaolmel had again buried it in a park – this time in Royal Park, Melbourne, near the zoo.

Kaolmel, who had been released on bail pending an appeal, visited Treloar, and the pair struck a deal: in exchange for the £50 reward the Memorial was offering for the return of the bell, and assistance in securing clemency, Kaolmel would give the Memorial information leading to its recovery.

John Treloar during the First World War. Treloar played an important role in establishing the Memorial.

John Treloar used his own money to help finance the investigation.

Although Treloar warned him against going to the newspapers, Kaolmel agreed to speak with The Sydney Morning Herald, hoping for an additional reward.

“In late December, the newspaper, keen for a scoop, drove Kaolmel to Melbourne,” Rutherford said. “They dug up the bell, but they didn’t get a chance to take photos, so they stopped on the trip back, and re-enacted the recovery of it.”

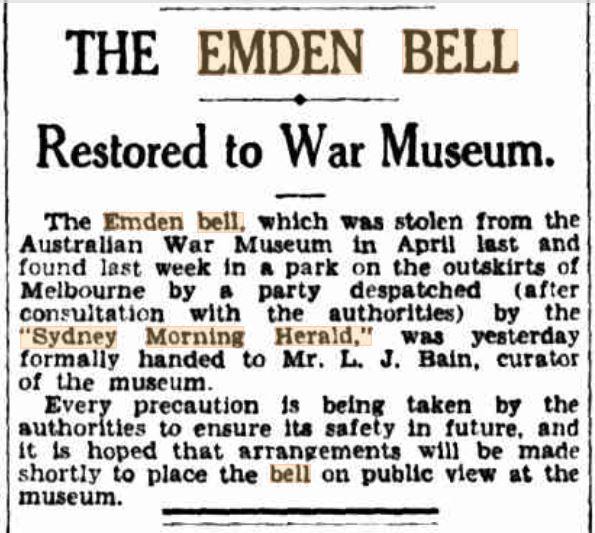

Although police originally wanted to hold the bell as evidence, the newspaper returned it to the Memorial in January 1934.

Kaolmel cancelled his appeal and was imprisoned at Long Bay Jail. He applied to have his sentence reduced and wrote to Treloar asking for help because his wife Constance was pregnant and alone.

Treloar decided not to support his application for early release because he had gone to the press, but he did ask authorities that if the sentence was reduced, it be on condition that Kaolmel gave a detailed account of the theft.

In April 1934, a year after the theft, Kaolmel was interviewed by Treloar and Memorial curator Les Bain.

He admitted he had first stolen the bell from Garden Island and that he had tried to sell it for a large sum of money but wasn’t successful.

An article in The Sydney Morning Herald on 2 January 1934 reporting on the recovery of the bell.

An article in The Sydney Morning Herald on 5 January 1934 about the theft.

An article about the bell in the Morning Bulletin, Rockhampton, on 16 January 1934.

Treloar and Bain wanted details of the second theft to improve security at the museum and to discover whether Kaolmel had accomplices, particularly among Memorial staff.

“It’s a heavy bell and it weighs about 50 kilograms,” Rutherford said.

“It really requires two people to move it comfortably, and although it can be done by one person, they found it hard to believe only one man had been involved.

“He had earlier alluded to others being involved, but he insisted during this interview that he had acted alone.

“They didn’t really trust him because he had a tendency of fibbing, so they asked him the same questions in different ways on multiple occasions to make sure they got a consistent story.”

When the bell was recovered, there were fears it was not the real bell, and a number of tests were conducted to confirm its authenticity.

Fearful of another theft, Treloar had a replica made. The replica would be displayed in place of the original for the next 40 years.

“It’s an amazing story,” Rutherford said. “And even without the thefts, it’s a very special object.”

The original Emden Bell is now on display in the First World War galleries.