The Great Escape of 1918

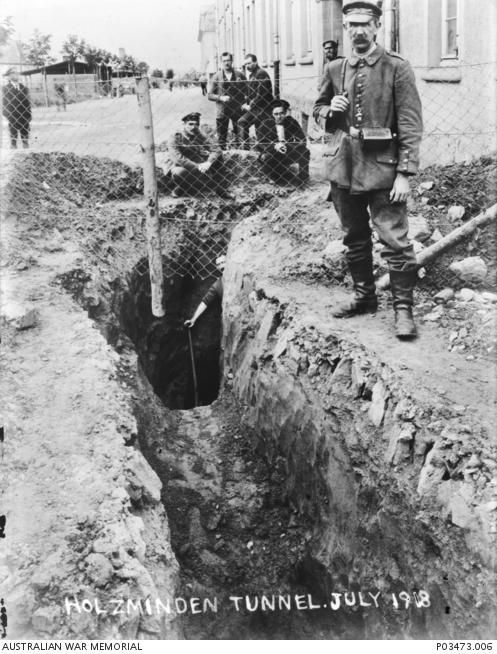

The exposed escape tunnel leading from the Holzminden Prisoner of War Camp, in Germany. The photographer was Private Dick Cash.

One of the most well-known stories of the Second World War, the Great Escape from Stalag Luft III in 1944 was popularised by the 1963 film starring Steve McQueen, James Garner, and Richard Attenborough.

Less well known is that the original escape attempt was inspired by an equally daring escape that took place during the First World War.

In 1918, a group of 29 British officers escaped under the noses of heavily armed guards at Holzminden prisoner of war camp in Germany.

The prisoners took more than nine months to dig an 80-metre tunnel using sharpened cutlery and bowls before escaping in July 1918. Of the 29 men who escaped, 19 were caught and 10 reached Holland on foot.

Their story is told at the Australian War Memorial as part of the Great escapes exhibition, which features stories of Australians who attempted to escape captivity during the First and Second World Wars.

“People tend to think of mass tunnel escapes as a Second World War thing, but they happened in the First World War as well,” said exhibition curator Jennie Norberry.

“Holzminden very much parallels Stalag Luft III in the Second World War in that it was a camp that was created for people who had attempted to escape previously.

“It became famous after the war as a ‘boys-own adventure’ type story, but it hasn’t lasted in public memory as well as the Great Escape has.”

Two German guards inspect an exposed section of an escape tunnel leading from the Holzminden Prisoner of War Camp.

Dubbed “Hellzminden” by the prisoners of war, the camp held between 500 and 600 British and Dominion officers, and 100 to 160 orderlies.

The camp commandant, Karl Niemeyer, had a reputation for cruelty, and conditions were particularly severe. There had been numerous escape attempts, but virtually all escapees were recaptured within a matter of days.

This time, the men concealed the entrance to the tunnel under a staircase in the orderlies’ quarters and used biscuit tins with the ends punched out to form an air shaft.

“The plan was for 86 officers to escape into a neighbouring field, but when they were making their way through the tunnel, an officer got stuck and brought down part of the roof as he struggled to free himself,” Norberry said.

“The tunnel started to collapse, so only 29 made it through, and the rest of them had to crawl backwards to the tunnel entrance to get out as others were still trying to come through.

“They were not discovered until the next morning when the commandant of the camp ran in to the last two officers who came out of the tunnel covered in dirt; he physically ran into them, and that’s how the Germans first discovered the escape and the tunnel.

“Not long afterwards, the local farmer rocked up in a fury to complain that all of his fields had been trampled because of where the tunnel exit was.”

Sergeant Peter William Lyon, 11th Battalion, of Perth, WA.

Among the 29 men who escaped that night was Captain Stanley Purves, of No. 19 Squadron, Royal Flying Corps. A Scottish engineer before the war, Purves was captured after his aircraft was shot down in 1918. He successfully escaped to Holland using a hand-drawn map and a small improvised compass that he had made from a pair of needles concealed in a paper wrapper for a Gillette safety razor blade.

After the war, Purves moved to Australia with his wife Sybil and worked for the engineering company that constructed the Sydney Harbour Bridge, and later became the general manager of the Goliath Cement Works at Railton in Tasmania.

Others were not so lucky. West Australian Lieutenant Peter Lyon of the 11 Battalion had already tried to escape from Holzminden twice before.

This time, he and two British officers took off towards Holland, hiding in woods during the day and avoiding major roads and villages by night.

Armed with a compass, a map of Germany, some money, and a cut of bacon, he managed to evade recapture for 12 days, but was caught by German sentries while crawling to the Dutch border north of Gronau.

Lyon was one of 19 escapees who were recaptured and brought before a German military trial, where they were sentenced to six months’ imprisonment for mutiny and destroying government property.

“What we have on display from his private records is the charge sheet from his court martial which lists all the people who escaped, and those who were recaptured,” Norberry said. “They were confined to their cells with bread and water and no lighting, and sentenced to six months imprisonment for mutiny and destroying imperial government property, but the sentence was never enforced, as Germany was by now losing the war.”

Australian Private Dick Cash, of the 19th Battalion, was a photographer before the war.

Australian Private Dick Cash, of the 19th Battalion, took photographs of the exposed tunnel after it was discovered.

He was not among those who escaped that night, but he had played an instrumental role in the escape.

“When you read books about Holzminden, they often talk about this mysterious map maker who nobody knew about, but it was actually Dick Cash,” Norberry said. “Dick Cash was a photographer before the war and his skills would prove invaluable.”

Cash had been captured at Bullecourt in May 1917 and was an orderly at Holzminden.

“He managed to trade with the guards, using items from Red Cross parcels to obtain a camera and military maps of Germany, which he photographed in sections,” Norberry said.

“He managed to get plates, chemicals, developing paper, and a bicycle lamp, and he was hidden in one of the rooms in Holzminden where he set about photographing and producing 300 copies of the map, which he gave to selected officers who sewed them into secret pockets in their shirts.

“Cash had been wounded before he was captured, and he was offered a place, but he said no because he wasn’t well, and he didn’t think he was strong enough to do it.”

Cash was awarded the Meritorious Service Medal in recognition of his role.

Today, his maps and photographs are a lasting reminder of what was truly a great escape.