The Heroic Tragedy of William Symons VC

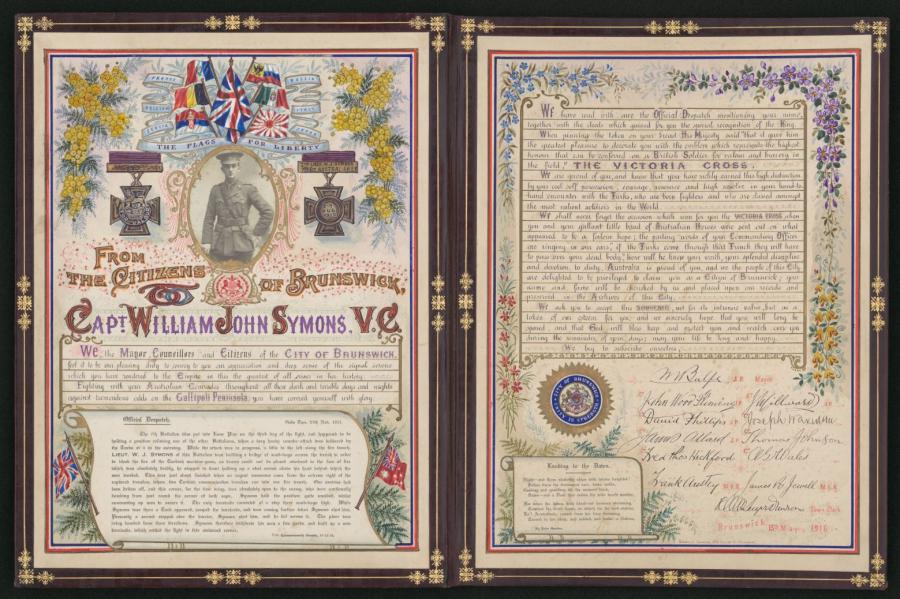

The Memorial was fortunate to have recently acquired an illuminated testimonial presented in 1916 by the Brunswick City Council to Captain William Symons, a Gallipoli recipient of the Victoria Cross. The highly decorative testimonial was made by Messrs. Arnall & Jackson, a stationery and printing firm on Collins Street in Melbourne, for the mayor, councillors and citizens of the City of Brunswick to publicly recognise Symons’ heroism during the Gallipoli campaign.

A high degree of craftsmanship went into the testimonial, which consists of two certificates, hand illuminated by watercolour, mounted into a timber folder and bound in a richly embossed and gilt leather. The certificates are painted with national trees and flowers, such as wattle, the flags of the British Empire and its allies, and the seal of the City of Brunswick. One certificate features a photographic portrait of Symons and, in handwritten ink, the text of the official citation for his Victoria Cross.

Symons received the testimonial from Brunswick’s mayor, Matthew Balfe, in what the Ballarat Star described as “a patriotic carnival” at Brunswick recreation reserve on Saturday 13 May 1916. The presentation was made before a sizeable public crowd that included Brunswick’s Commonwealth and state parliamentarians, Frank Anstey and James Jewell. Symons was also gifted 25 sovereigns (the equivalent of £25; approximately $3,000 today) “by admirers of his gallantry”.

The presentations were made in honour of Symons’ leadership and heroism during the Battle of Lone Pine in August the previous year. Symons, then a lieutenant in the 7th Battalion AIF, was tasked with leading a small party of men to recapture and hold Jacob’s Trench, a post on his battalion’s exposed right flank. On assigning him with this task, Lieutenant Colonel Harold “Pompey” Elliott handed Symons his own revolver with the remark, “I don’t expect to see you again, but we must not lose that post.”

The initial charge by Symons’ party drove out the Ottoman defenders, only for the Australians to be almost encircled by the enemy. Over the following 12 hours, Symons demonstrated sustained and distinguished leadership. He repeatedly rallied his men to fend off frequent attacks, erected and maintained a barricade, and withstood two attempts by the Ottoman Turks to set fire to the overhead timber covering. The fierce resistance by the Australians eventually persuaded the Turks to discontinue their attack, but retaining the post had been costly. Symons later wrote to his mother, “I only had 40 men with me in the firing line … When I came to muster them afterwards we only had about 15.” Symons himself had been wounded in the left hand, after a bullet had shattered the stock of his rifle.

Symons fell ill with gastroenteritis shortly after Lone Pine and was convalescing in Australia when he was presented with the testimonial. Three weeks later, he re-embarked for overseas service as commander of D Company in the newly raised 37th Battalion. The unit spent four months training on Salisbury Plain in England before proceeding to France, and the Western Front, in November. Symons was wounded in the head while leading a raiding party in February 1917 and severely gassed at Messines in June. He spent six months under treatment or convalescing from the mustard gas attack, before re-joining his battalion in January 1918.

Symons (third from left) with other officers of the 37th Battalion about to embark from Melbourne, 3 June 1916. PB0829

Symons saw further action at Dernancourt and in response to the German Spring Offensive, before he was given an opportunity in August – alongside 13 other recipients of the Victoria Cross – to return to Australia and assist in a recruiting drive. The war ended before the men could have much effect, and Symons was discharged from service in December 1918.

Symons worked as a travelling salesman in the immediate post-war years, but struggled to maintain employment due to recurrent health problems. Suffering from insomnia, nervousness and shortness of breath, he had been temporarily granted a pension at 50 per cent capacity on his discharge from the AIF. As he further began to experience respiratory problems, hand tremors and increasing deafness, Symons reapplied to the Repatriation Department every six months for his pension to be extended.

Captain William Symons, wearing the ribbon of his Victoria Cross, c. 1916–18. H06206

In 1923, seeking to increase his employment prospects, Symons commuted his pension and went to the United Kingdom to study paper making. He decided to make the move permanent and, joined by his wife Isabel and their two daughters, settled in Greater London and turned his hand to business ventures. He experienced initial success as a catering manager in Wembley, until his health problems returned. Experiencing frequent “stomach trouble”, further hearing loss, insomnia and “severe head troubles”, Symons was barely able to work in 1926 or 1927 and the family (now of five) was left near destitute. As Symons wrote to the Repatriation Department, “I have been in business but lost control through illness.” He attributed his “head and ear trouble to a blow by sandbags which were hit by a shell on Gallipoli”, and appealed for assistance. He was granted a pension, at a rate of 30 per cent incapacity, for 12 months.

Symons was able to recover his health and finances and during the 1930s found considerable success as managing director of a series of engineering and construction companies. He later became manager of a greyhound track and even returned to military service during the Second World War. As a lieutenant colonel, he commanded the 12th Battalion, Leicestershire Home Guard from 1941 to 1944.

Symons’ medals, including his Victoria Cross (at left), were donated to the Memorial in 1967, two years after they were first sold. RELAWM16566

Yet, Symons could not escape his health troubles. He was left concussed after a car accident in 1941, was discharged from the Home Guard due to ill health in 1944 and by 1947 had been diagnosed with “a mild and slowly progressive dementia”. Symons’ wife Isabel was left to petition the Repatriation Department for an adequate pension. Despite Symons going into full-time nursing care in January 1948, the Repatriation Department had only granted a 30 per cent pension since physicians were unable to determine whether Symons’ condition was caused by his war service or the car accident. A full pension was finally granted in March, three months before Symons died, on 24 June 1948, at age 58.

Three decades after the Armistice, William Symons VC had continued to experience the effects of his war. Isabel was forced to sell her husband’s medals due to financial strain in the 1960s but the illuminated testimonial, a community’s tribute to Symons’ service and heroism, remained with the family for another five decades.