In his own words

Captain C.E.W. Bean watching the Australian advance through a telescope near Martinpuich, France, on 26 February 1917.

For more than four years, Charles Bean would sit up late each night writing in his diaries, often by candlelight or moonlight and struggling to keep his eyes open.

Sometimes, he said, daylight would find him still at work, falling asleep at each full stop and then waking to write each successive sentence.

But Bean was determined to continue. He’d gone off to the First World War as Australia’s official war correspondent when he was 35, and was witness to it all.

It was said that no other Australian saw as much of the fighting during the First World War as Bean did, and he filled 226 notebooks with compelling first-hand accounts of the battles and his own personal thoughts and ideas about the war.

From the trenches of Gallipoli where he was wounded and later mentioned in despatches for his bravery, to the bloody battlefields of the Western Front where he was horrified by the heavy loss of life and the sheer scale of devastation, Bean never faltered, reporting from the front, often in unimaginable conditions and at great risk to himself.

The diaries, which he kept safe in bank vaults in Cairo and London for fear of losing them, became the foundation for the Official History of Australia in the First World War and provided some of the most comprehensive insights into the sense of terror, tragedy and sheer pointlessness of it all.

Now, a century after he wrote them, and 50 years after his death, extracts from his diaries have been printed together for the first time in The Western Front Diaries of Charles Bean.

Informal portrait of Captain C.E.W. Bean knee deep in mud in Gird trench, near Gueudecourt in France, during the winter of 1916-1917.

Edited by the Memorial’s longest serving staff member, esteemed historian and curator Peter Burness, the book features more than 500 photographs, sketches and maps, and provides a unique insight into the Australian experience on the Western Front.

“This is not another Bean biography … nor is it a book written by me: what is reproduced is Bean’s own writing drawn from his own personal, private diaries,” Burness said.

“The published selections give readers a detailed insight into Charles Bean’s thoughts and experiences. They tell us a lot about the war; and about the main characters, from the King and Lloyd George and the generals, to the ordinary soldiers in the trenches; of men facing battle; of courage and sacrifice. But they also reveal a lot about their author, providing a glimpse into aspects of a vital period of the war from the pen of a close and trained observer.

“In many respects, he didn’t just record the story: he was part of the story himself. He was wounded at Gallipoli – had a bullet in his leg for the rest of his life – and he was there in all the big battles… but his diaries are terribly honest.

“He hasn’t cut out or torn out pages or anything like that. He’s put a note on the cover of all 226 notebooks saying in effect, ‘please understand that this is what I was thinking at the time, it’s not my long-term view, it’s not my view any more’, and all those sort of things; but he didn’t try to censor them or mutilate them in any way.

“He wrote them in some of the most appalling conditions, so it was a brave thing for Bean to do, to allow access to the records of his own personal thoughts and experiences, including deep and dark moments.”

Among the darkest moments was those during the battle of Pozieres from 23 July 1916. These would haunt Bean for the rest of his life.

“The shelling was enormous and worse than anything Australians had experienced to that date, [or] have experienced since, and it shook him up,” Burness said.

“At a time when most correspondents might stay behind the front line and maybe interview people in hospital, he constantly took himself up to that battlefield. He hated it. He was terrified. And some of the things he wrote during those evenings, you just wonder what was happening to him when he wrote with such passion about what he saw. It just flowed out of him – the terror, the horror, the pointlessness of it all – but he keeps going back there. He didn’t have to, but every time he was in that area, he would go back and just walk over that battlefield because so many Australians had died there.”

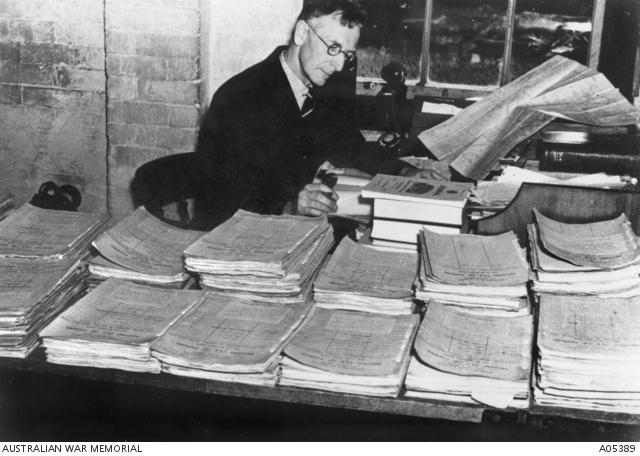

Informal portrait of C.E.W. Bean working on official files in his Victoria Barracks office during the writing of the Official History.

Bean stayed at the front until the end of the war and was deeply affected by what he saw. The war had changed him, and he dedicated the rest of his life to recording and sharing the troops’ stories and experiences.

“He was a man who was full of ideas and opinions, and he had a vision for Australia,” Burness said.

“He thought Australia was going to be a great nation and the war would be proof of the fact that it could rise to the occasion …

“He had a strong sense of what a man should do, what a man’s duty was, and how a man should behave. He had very high ideals of duty and honour … [but] what you discover when you are in one of those great battles from the First World War is that it just didn’t matter. The brave men got killed alongside the not so brave, and the idealistic were killed alongside those who just wanted to be out of the place. And to him it was a great levelling experience.

“He said that these men went off on this great crusade to change the world and make it a better place and he was disappointed after the First World War that the world hadn’t become a better place, but he said that we can’t forget the men who tried to make it so.”

He was determined their service and sacrifice would not be forgotten, so he set about establishing a national memorial and museum – the Australian War Memorial – in their honour.

“I joined the Memorial 45 years ago and Charles Bean was part of the memory of the place,” Burness said. “Whether he would think I’ve done a good job or not, I don’t know, but he would be pleased that people are accessing his diaries. The bottom line is that he wanted all those Australians who went off to the First World War to be remembered, and this is another way of remembering them, so he’d be delighted I’m sure.

“His name’s always been a presence in the background of my life … and his opinions matter … so it’s been a privilege. It’s always been a privilege.”

The book, The Western Front Diaries of Charles Bean, retails at $79.99 and is available at the Australian War Memorial shop, online, and at good bookstores nationally.

Read Peter Burness’s Wartime article about Charles Bean here.

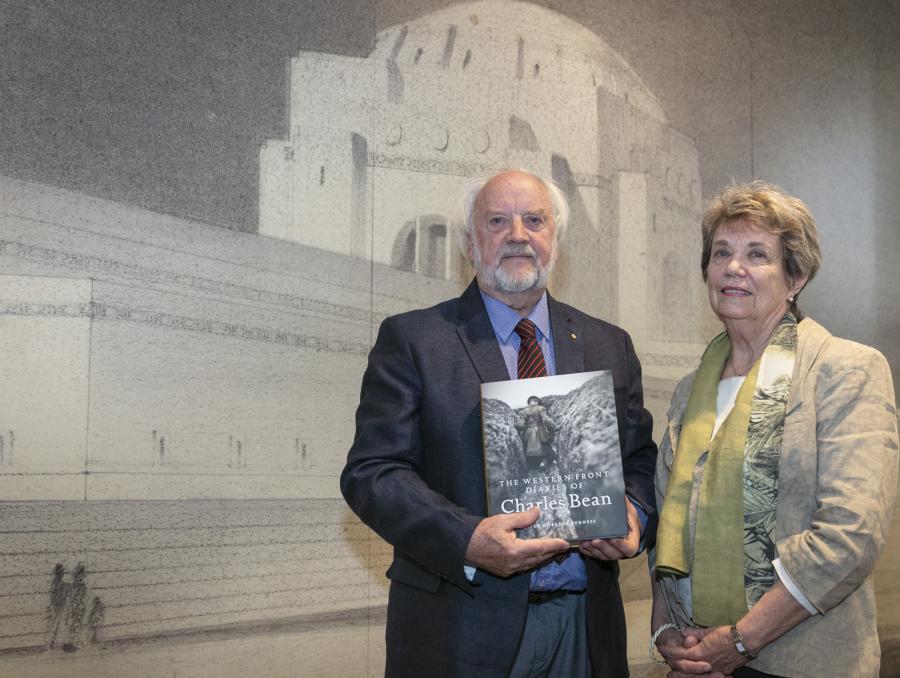

Peter Burness with Charles Bean's granddaughter Anne Carroll at the book launch.