The Ypres lions

In medieval times two stone lions bearing the coat-of-arms of Ypres stood at the entrance to the Cloth Hall, the town’s civic and commercial centre. Centuries passed and the town’s glory faded. The lions were moved to the Menin Gate and stood there during the war while Ypres was reduced to ruins by German artillery fire. The lions, broken and scarred, were later recovered from the war rubble and in 1936 the Burgomaster of Ypres presented them to the Australian Government as a token of friendship and an acknowledgement of Australia’s sacrifice. Today they once again stand as sentinels seen by everyone entering the Australian War Memorial in Canberra.

The Menin Gate lions

by Elizabeth Burness.

This article originally appeared in the Journal of the Australian War Memorial, No. 13, October 1988, pp 48-49.

In 1936, two large stone guardian lions were donated to the Australian War Memorial by the burgomaster of the Belgian city of Ypres. The lions, carved from limestone, were given to the Australian government as a gesture of friendship and, in exchange, in 1938 the Memorial gave a bronze casting of C. Web Gilbert's sculpture Digger on behalf of the Australian government. The inscription on the casting of Digger reads:

'In assurance of a friendship that will not be forgotten even when the last digger has gone west and the last grave is crumbled.'

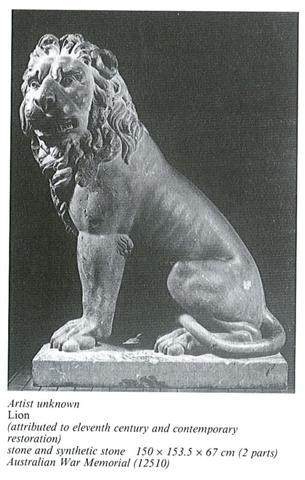

In 1988, the two stone lions look very different to the way they looked when they arrived in Australia in September 1936. During the First World War, shell-fire toppled both lions from their plinths on either side of the Menin Gate access into Ypres. The gate, one of only two access points into the medieval fortified city, was, in fact, only a cutting between the ramparts of a fortified wall through which the allies marched to the battlefields of the Ypres salient between 1914 and 1918. Both lions were deeply chipped across their backs, and one lost its right foreleg. The other incurred some pulverization on one side of its head, and major damage elsewhere that reduced it to only a head and trunk ending just below the rib cage.

When the lions arrived at the Memorial in September 1936, the building was not yet complete. It was intended that the lions should be restored, but it would have been difficult to display them as they would have required an extensive exhibition area. For several years the lion with the missing leg was on display in the Memorial, but the lion with only a head and torso has never been shown.

In recent years an ethical question has arisen concerning whether or not missing portions of such historical relics should be reconstructed. It was thought that such a reconstruction could interfere with the historical value of the items. In 1985, it was decided to reconstruct the missing pieces of each lion in such a way that it was obvious which were the original and which were the reconstructed parts. The reconstructions were designed so that they could be dismantled to return the sculptures to their original state, should that be necessary. In order to complete this reconstruction, it was crucial to discover what coat of arms had appeared on the missing shields that were held in the paws of both lions before their wartime damage.

In May 1986, I recovered the missing information with the help of the curator of the Salient 1914—18 War Museum in Ypres, Mr Tony de Bruyne. Information from the tourist office in Ypres, material on the seals of the city from the public library and, in particular, access to an original photograph by the prominent local photographer `Antony', contributed to the gathering of the vital details. Mr de Bruyne was able to contact the daughters of the late Mr Antony who hold the glass plate originals of all the pre- and post-First World War photographs taken by their father.

In 1987, the reconstruction of the two lions was completed by Kasimiers L. Zywuszko, a Polish-born sculptor, with the assistance of the period photographs obtained from Ypres. The method chosen involved modelling the missing parts in clay, then taking plaster moulds of the parts and filling them with a mixture of block crushed marble and araldite, with pigment tints added. Once the mixture had set, the moulds were broken free and the cast pieces finished by hand. The pieces were not glued to the original stone, so the reconstruction was not permanent. The battered appearance of the lions was still apparent and the effects of shell-fire could still be seen.

Many allied soldiers leaving Ypres for the battlefields beyond would have passed the lions standing guard at Menin Gate. Certainly members of the British Expeditionary Force would have seen the lions in situ. It is unlikely, however, that many Australian soldiers would have seen the lions looking as they do in this photograph.

The events of 1914—18 throw some light on what happened to the city of Ypres and to the lions. In the autumn of 1914, the opposing armies attempted to outflank each other, moving north towards the Belgian coast. The British defences at Ypres formed a major salient, a bulge, in the allied line. The bombardment supporting the German attempt to take the town reduced it to a ruin. Much of medieval Ypres, including the Cloth Hall and St Martin's Church, was destroyed. Photographs of the town taken early in 1915, however, show that the lions remained intact. In September and October of 1916, the 1st Anzac Corps changed places with the Canadian corps, and came to the Ypres salient from fighting at Pozieres in France. During this period the Ypres salient was relatively quiet. However, 1917 brought the third battle of Ypres, in which all five Australian divisions were engaged. Entries from some of the diaries of Australian infantrymen at this time are revealing. On Monday, 17 September 1917, Private Leicester Grafton Johnson of the 20th Battalion, AIF, wrote: `Ypres that much war worn city is now reduced to a mass of ruins. Only the walls of the fine Old Cathedral are left standing' (AWM 3DRL 7349). Private J. N. Shearer of the 15th Battalion, AIF, noticed on Tuesday, 25 September 1917, that

'Shells from guns of huge calibre were tearing up the swampy marshes behind and in front of us . . . the muddy roads were strewn with wreckage of transport lorries; dying horses and mules writhed in agony along the Menin Road' (AWM 3DRL 3662).

What happened to the lions during this bombardment and in the later stages of the war remains unclear.

After the armistice of 11 November 1918, it took three years of active searching in the Ypres area to find the unburied allied dead, and those scattered in graves where they had fallen. However, a memorial was needed for the 88 500 officers and men, including 6176 Australian soldiers, who had no known grave, one of whom was my great-uncle, Corporal Gordon Rinder. The site chosen for this, the largest memorial to the missing from British and Commonwealth countries in the world, was the Menin Gate. An imposing archway surmounted by a recumbent lion, this memorial bears the names of 54 900 dead from Britain and Commonwealth countries who have no known grave. So many British and Commonwealth soldiers passed through this gate on their way to the front, never to return, that it seemed a fitting site for their memorial.

A photograph, taken in 1920 by a Mrs G. H. Webster, shows one of the lions by the roadside near the Menin Gate at Ypres. It is probable that the two stone lions lay in the rubble around the Menin Gate cutting from 1920 until April 1923, when work on the memorial foundations commenced. The lions were removed to a place of safety in the market place along with other shattered remains of buildings and statuary. They were then shifted and stacked with other broken masonry under the ruins of the Cloth Hall.

Mr de Bruyne, in his efforts to help date the lions, postulates the theory that they may have stood originally at the foot of one of the stairways leading into the Cloth Hall. They had previously stood either in the market place or by one of the other gates into the town of Ypres, the earliest of which was the Lille Gate, dating from 1383. The Menin Gate was originally the medieval Hangoart Gate, later known as the Antwerp Gate. After being fought over by the Austrians, Dutch and French, this main gate was named after Napoleon Bonaparte, who visited Ypres in 1804, and it had an imperial eagle carved into the stonework. After Waterloo, in June 1815, when Belgium was united with Holland, the Napoleon Gate was renamed the Menin Gate, since the road through it led to the town of Menin. In 1838 Ypres became Belgian, and in 1852 the government decided that the fortifications around Ypres were no longer required. All the gates were removed except the Lille Gate, and the Menin Road cutting remained open. The lions were placed on either side of the cutting some time between 1852 and 1858.

Most of the interesting historical buildings of Ypres were destroyed between 1914 and 1918. What a terrible irony that the city of Ypres, which began in the tenth century as a cluster of small huts situated on swampy ground, should be reduced to that squalid state again. When the townspeople returned to their smashed city, they decided to rebuild it exactly as it had been in its heyday. All the work involved in the rebuilding was paid for by Germany, as one of the penalties imposed upon it by the Treaty of Versailles, which officially ended the war in 1919. It took more than forty years to rebuild the razed city, and now much of Ypres is the same age as Canberra. While the emphasis has been on the medieval and later splendour of the city, the First World War is not forgotten.

Housed in the rebuilt Cloth Hall is the Salient 1914—18 War Museum. The museum has concerned itself with every aspect of the Great War, particularly as it relates to the Ypres salient. As well as dioramas, including one of the old Menin Gate, models, badges, weapons, equipment, photographs, pictures, maps, relics of old Ypres, documents and uniforms (including a First World War Australian uniform presented to the museum in 1986 by the Australian War Memorial), the museum holds the Web Gilbert bronze casting of Digger. The city of Ypres received the honours of the British Military Cross and the French Croix de guerre, and both these and their documents are also displayed.

From 1964 to 1968 the city of Ypres became a `twin town' with cities in Germany, Britain and France. While the idea of twinning between towns and cities has great merit, the Australian War Memorial has a more permanent reminder of friendship and commemoration between Australia and Ypres in the two huge battle-scarred guardian lions. Their reconstructed forms, complete with their shields, now give Australians an inkling of the heritage of Ypres that they represent.