The eager soldier: the story of Theodore Willard Wright

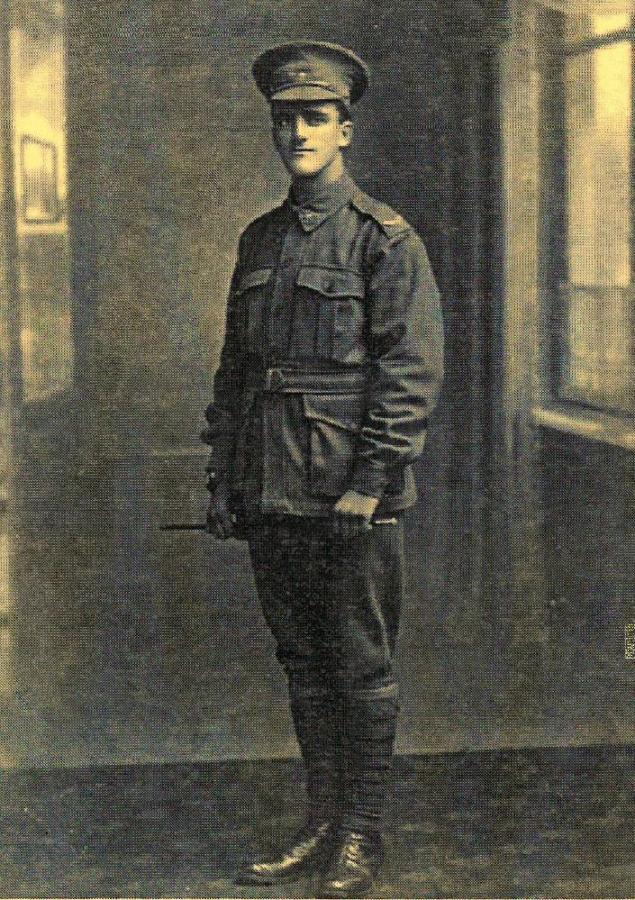

Theodore Willard Wright in his army uniform.

Images courtesy of Barbara Adams.

Theodore Willard Wright wasn’t going to let a case of “bad teeth” stop him from enlisting during the First World War.

A promising newspaper journalist and compositor from Peterborough in South Australia, Theo Wright tried several times to join the Australian Imperial Force after war broke out in 1914, and eventually saved up to buy a set of expensive false teeth to pass the medical.

His niece, 85-year-old Barbara Adams, smiles as she tells the story.

“He kept imploring and asking to be in the army and they kept saying no because of his teeth,” Mrs Adams said, flicking through the pages of her book, The Eager Soldier, a collection of his many letters which have been kept and cherished by his family for 100 years.

“Eventually, the recruiting officer said if he could eat a bush biscuit in front of him, they would let him in, false teeth and all. So he ate the bush biscuit and was allowed to go … He was so eager. That’s why I call him the eager soldier. They had no idea what they were letting themselves in for.”

Portrait of the Wright family taken circa 1912.

Left to right: Bertha, Theo, Laurel (in front), Alice Jane, Constance, Frederick, Joseph, Daisy and Margaret.

Wright, who was born in Mount Gambier on 30 December 1892 to Joseph and Alice Wright, was one of seven children. His youngest sister Laurel was Mrs Adams’ mother and she would speak fondly of her beloved older brother who went away to war, but never came home.

“She always talked about him, so we always felt we knew him,” Mrs Adams said ahead of a Last Post ceremony to mark the 100th anniversary of his death on the battlefields of Belgium. “He used to call her little-un and she loved him dearly … In one letter he says, we’ve heard they’re not so strict now as regards to the teeth. He was so eager to go.”

Wright had already lost two sets of false teeth “as a result of being so fond of swimming”, and his boss had given him a “five bob” pay rise to encourage him to stay at the newspaper where he worked, but he was determined to join the army and seek adventure.

“It’s me for a soldier’s life now, Hurrah – rah-rah!” he wrote to his cousins when he was finally accepted for service in February 1916. “I’ve lost two bally sets of teeth ... The first set I lost in the Valley Lake soon after Xmas. I then got a 12 guinea set and they were absolutely perfect. Last Wednesday I went with a swimming party to the Glenelg River … This time I put my ‘ivories’ into my pocket for safety. When I had finished and was handling my clothes the d---- things fell out of the boat into deep water. I spend a lot of time and energy diving for them but hadn’t any luck. Am I not a ‘Jonah’ altogether?”

Wright was finally posted to the 43rd Battalion and left for England and the Western Front, leaving behind his family and his fiancée, Miss J.M. Opie.

“Although I feel sad at the thought of leaving you all, I am quite contented,” he wrote. “I feel I am doing my bit and hope that the 43rd will make a reputation for itself over and yonder.

“Don’t worry about me at all, I am able to look after myself and am quite prepared for anything that may come to pass.

“Whatever happens ‘tis my intention to play the game in everything and not give you any cause for sorrow. If I go under, dear ones, don’t be sorrowful, for I am not afraid to go. I haven’t been an angel by any means, but I’ve tried to play the game.”

Theo Wright, far right, and his fellow soldiers in barracks at Salisbury Plain.

I never regretted joining up and can truthfully say that I have enjoyed life as a soldier. I have tried to play the game of life straight and clean and believe that I have succeeded … don’t mourn for me. I shall be happy to give my life for the cause should the necessity arise. Lovingly yours, Theo.

A budding poet and prolific writer, he also proved to be an able soldier and wrote as often as he could to his “dearest home folk”, who anxiously awaited news from the front. His mother would send the letters and postcards she received to each member of the family, who would all initial them, before finally sending them back to his mother for safekeeping.

In June 1917, Wright’s battalion took part in the battle of Messines, making “the best of a bad job”, and paving the way for the Third Battle of Ypres, which began in earnest on 31 July 1917 with the British attack at Pilckem Ridge. At this point the 43rd Battalion was in the front line near the Belgian town of Warneton, and like many soldiers, Wright had again taken up his pencil to write a letter to be sent home in case of his death.

“I never regretted joining up and can truthfully say that I have enjoyed life as a soldier,” he wrote in what would be his last letter. “I have tried to play the game of life straight and clean and believe that I have succeeded … don’t mourn for me. I shall be happy to give my life for the cause should the necessity arise. Lovingly yours, Theo.”

Now a corporal, Wright was in a trench with a machine-gun crew when a shell dropped nearby. He was badly wounded in the blast and reportedly died a short time later. He was just 24 years old, and would never see his beloved family or fiancée again.

Wright was buried near where he fell, but his grave was lost in later fighting. His name is inscribed on the Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing at Ypres, alongside the names of more than 54,000 others, including some 6,000 Australians, who died in the fighting in Belgium but have no known grave.

His boss from Mount Gambier, who was also in the battalion and was not far away when Wright was killed, said he “was the best mate you could want to have … a very good man in every way”.

Heartbroken at the news of his death, Wright’s fiancée didn’t marry until she was 30, and would die in childbirth at the age of 33. His mother never got over his death and cherished his hand-written letters for the rest of her life.