They had to remember they were soldiers, albeit female

By August 1944 there were 2,223 Japanese prisoners of war in Australia. Of these 1,104 were housed in Camp B of No. 12 Prisoner of War Compound near Cowra, in the central west of New South Wales.

The Italian, Japanese, Taiwanese and Korean prisoners of war interned at Cowra were treated in accordance with the Geneva Conventions. But relations between the Japanese prisoners of war and their guards from the 22nd Garrison Battalion were poor, due largely to significant cultural differences.

The Japanese prisoners had made no firm plans for a mass breakout until early August, when they were made aware of plans to separate the B compound inmates, relocating the junior ranks to a camp at Hay in western New South Wales. When informed of the transfer, the Japanese prisoners of war in B compound made the decision that they would launch a mass escape the following day.

In the early hours of the morning on 5 August, 1944, Australian Army personnel in the Australian Women’s Army Service (AWAS) and Army camps were awoken by the noise of almost a thousand Japanese prisoners armed with gardening tools, baseball bats, axes and knives, breaking through the fences of the camp.

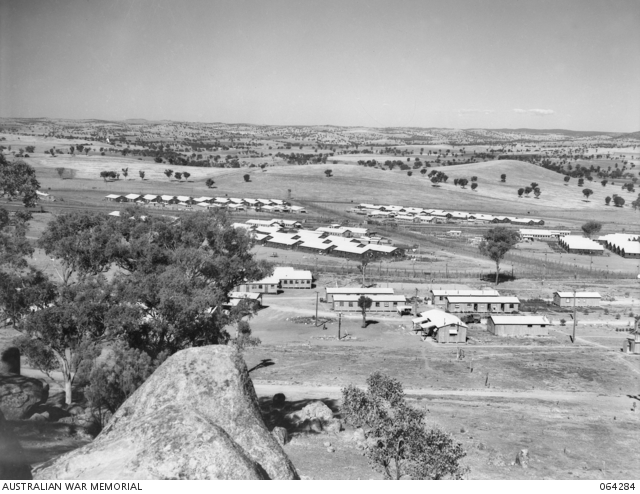

View looking west showing the compounds of the 12th Australian Prisoner of War Camp at Cowra, with the Group Headquarter buildings in the foreground.

As the home of the Australian Recruit Training Centre, Cowra was a temporary base for many thousands of Australian servicemen. It was not generally known, however, that approximately 100 Australian Womens Army Service personnel of 42 AWAS Barracks, under the command of Lieutenant Nelly Gould (NF392288), and three AWAS ambulance drivers from the 2nd Australian Ambulance Car Company, were also stationed there.

The morning of August 5, 1944 “struck terror in the hearts of all AWAS despite their outward calm.” According to Nelly Gould, AWAS personnel had often expressed concern about the possibility of an escape attempt. However, there were never any drills or orders issued for such an eventuality. “With the lives and welfare of the AWAS now solely her responsibility … [Gould] assembled all personnel and issued orders, harsh as they were, to ensure maximum safety.”

During the days and weeks following the breakout, AWAS personnel were confined to their camps. Leave was withheld for all personnel in both the Prisoner of War and Training Camps. AWAS were told there was to be no shouting or running (unless they were in danger), they were to move about the camp in groups, never alone, and their sleeping huts were to be locked at night. Because they were unarmed, they were escorted to their various posts during the day.

During the first week, in the bitter winter cold, Nelly Gould, accompanied by an armed escort would set out several times a night to investigate reported sightings close to the Barracks. Requests for her own weapon were refused.

Portrait of Lieutenant Nelly Gould, Officer in charge of AWAS Barracks, Cowra, NSW

Lieutenant Nelly Gould (left) and Sergeant Joan Kennedy having an early morning cup of tea after spending the previous night searching for escaped Japanese POW’s from the Cowra Camp

It was several weeks before every Japanese prisoner of war was captured or accounted for. During this time, “the AWAS maintained a high standard of courage and morale. Later, because of the hardships experienced for so long, the girls were granted permission to transfer away from Cowra. It is to their credit that no applications were received.”

At the time of the breakout, Cowra became on official theatre of war. The AWAS serving at Cowra were the only members to serve in a declared battle area. Despite this, they were denied the benefits offered to the men who served at the time.

In November 1983, Gould applied to the Department of Veteran’s Affairs for a service pension. The Central Army Records Office (CARO) was contacted and asked to “advise if she was stationed at Cowra on 5 August 1944 at the time of the POW outbreak, and any other information you may have regarding her involvement in the breakout.” The response from CARO confirmed that she was serving with 42 AWAS Barracks but they were unable to provide any information as to the location of the unit at the time of the breakout.

A quote in the published history of the 2nd Australian Ambulance Car Company, posted at Cowra during the breakout, states that “it took many years of painstaking work before the girls were granted their rightful benefits.”

For more information about the Australian Women’s Army Service, and to research women who served with the AWAS during the Second World War, please see the information sheet on the Memorial’s website.