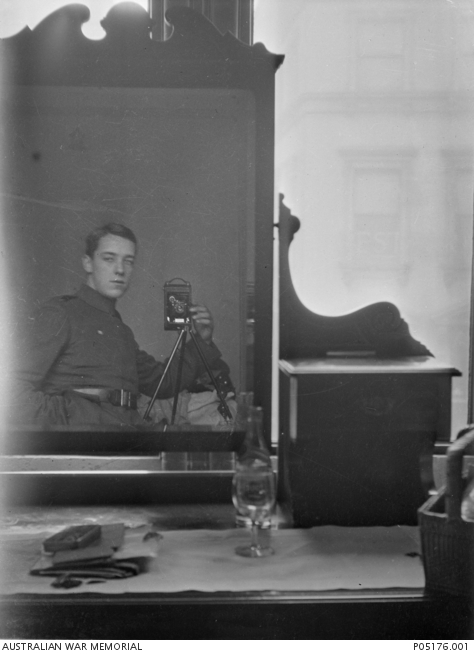

The saddest selfie

It’s a striking image of a fresh-faced young man taking a photograph of himself reflected in a dresser mirror more than 100 years ago.

Less than a year later, 21-year-old Captain "Rich" Baker was dead, one of the last Australians to be killed in action during the First World War.

A highly decorated flying ace of “exceptional determination and courage”, Baker was shot down over Belgium on 4 November 1918, the 10th anniversary of his father’s death, and just a week before the end of the war.

Today, his name is listed on the Roll of Honour at the Australian War Memorial.

Memorial historian Mick Kelly knows his story well.

“He was an amazing pilot, and was very skilled in the deadly combat of the skies,” Kelly said.

“He was described by people who flew with him as a fearless leader, and an amazing combat pilot, so he was highly regarded by all who knew him.

“He was quite something. It was phenomenal.”

Portrait of Thomas Charles Richmond Baker, ex AIF, in the uniform of a RAF cadet.

A passionate airman who was most at home in the cockpit, Thomas Charles Richmond Baker was born in Smithfield, South Australia, on 2 May 1897, the eldest son of Richmond Baker, a school master and farmer, and his wife Annie.

Rich, as he was known, loved to build model aircraft and dreamed of becoming a pilot one day

“He grew up in Adelaide, and was an exceptional sporting talent. He played Aussie rules, but he was also great at rowing and tennis, and he was awarded a scholarship for athletics.

“He was a cadet at school too, so he was soldiering from a young age; but he was quite keen on aircraft so it became a fascination for him as a young lad.

“He made model kits at home growing up and dreamed of becoming a pilot one day.

“He had a real passion for this new technology and the romance of flight, and he wanted to be involved in it.”

Mitcham, South Australia, 1915: Baker about to depart by train for further army training in Victoria.

He was working as a bank clerk for the Adelaide branch of the Bank of NSW when he enlisted with his mother’s consent in July 1915, and went on to serve with the 6th Field Artillery in France. His first major action was during the battle of Pozières in July 1916. The small French village in the Somme valley was the scene of bitter and costly fighting. The Australian Imperial Force lost as many men in less than seven weeks of fighting near Pozières and Mouquet Farm as it had during eight months on Gallipoli.

“It’s a real baptism of fire,” Kelly said.

Less than six months later, Baker was awarded the Military Medal for “great devotion to duty” on 11 December 1916, in repairing a telephone line under intense fire while serving as the telephonist for his commanding officer near Gueudecourt. His commanding officer was acting as a forward observation officer and the two men occupied an exposed position ahead of the Australian front line. While under constant fire from enemy snipers and artillery, Baker went out into the open four times to repair the line in 30 separate places to maintain communications.

A year later, in June 1917, he added a Bar to his Military Medal after he helped put out a fire in a gun position which had threatened to detonate about 300 rounds of high explosive shells near Messines.

“His artillery position was hit by German artillery and it started a fire,” Kelly said. “Baker was instrumental in putting out the fire, saving about 300 rounds from detonating and just devastating the position.

“He was like cold steel, that man. It’s quite incredible. He knew if he didn’t get in there, and get that fire out, they were all dead, so he did his best and managed to put the fire out and stop the rounds from detonating and killing them all.”

His quick actions prevented “certain disaster”, but Baker still longed to fly. He remarked that he was “almost green with envy” on seeing Allied aviators in action; and in late September 1917, his application to transfer to the Australian Flying Corps was accepted.

Nieuport, Belgium, c.1916. Gunners Thomas Charles Richmond Baker and Harrington of the 16th Battery, Field Artillery, AIF, relaxing in a dugout.

"It was his dream coming true,” Kelly said.

“He’d already seen significant service on the Western Front as an artillery man and signals officer, and he was highly decorated, even before he became a pilot.

“But the desire to fly was just in his blood. He’d dreamed of flying since he was a boy and he would have watched these new aircraft in action overhead, flying above him on the Western Front.”

Baker was initially accepted into the flying corps as a mechanic, but was later selected to undergo pilot training, qualifying as a pilot at the end of March 1918.

“Such was his skill, he was offered a position as an instructor,” Kelly said. “But he knocked it back because he wanted to be posted to an operational squadron and fight in the skies over France and Belgium.

“I think he just had that determination and wanted to test his mettle. He’d already tested it in combat on the Western Front, but he wanted to test it as a flier as well. And he certainly did that.”

Six Sopwith Camel aircraft ready for a flight. Note the kangaroo emblems on the fuselages.

Baker joined No. 4 Squadron and scored his first aerial victory while flying a Sopwith Camel, bringing down a Fokker D.VII in July 1918.

“He was one hell of a flier,” Kelly said.

“If you didn’t know how to control the aircraft, it would have you down on the ground as quick as a flash. But he obviously had a knack for it, and by the end of August, he had become an ace pilot, taking down another three enemy aircraft.”

When he met King George V, he told his mother the King, who seemed a “jolly decent sort”, had asked how he received the Military Medal and Bar, and “how many Huns” he had shot down.

Returning to operational flying in France, Baker shot down a further two enemy aircraft before the squadron was re-equipped with Sopwith Snipe fighters. He was promoted to temporary captain and made a flight commander on 24 October. He had brought down a further six enemy aircraft by the end of the month.

On 4 November 1918, Baker led a formation of Sopwith Snipes as part of an escort for a bombing operation against a German aerodrome near Ath in Belgium.

“The bombing raid was a success,” Kelly said. “But on the return journey, they encountered a large number of German aircraft. In the ensuring dogfight, four German aircraft were shot down. But when the Snipes regrouped, they discovered five of their own aircraft had been shot down, including Baker’s.”

Several pilots reported seeing his aircraft crash-land behind enemy lines, and Baker was initially recorded as missing in action; but despite searches by ground and air, he remained unaccounted for. A court of enquiry in February 1919 determined that he had been killed in action on 4 November, 10 years to the day after his father had died. Initially classed as an unknown British officer, Baker’s remains were later located and identified by an Imperial War Graves team in the Escanaffles Coummunal Cemetery at Hainault in Belgium.

One of his mates, and fellow ace pilot, Lieutenant Leonard Taplin described Baker as “one of the most brilliant boys … one of the best fliers I have ever seen.”

Baker was posthumously promoted to captain and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross on 23 May 1919.

During his brief but spectacular career as a fighter pilot, Baker had destroyed eight enemy aircraft, and was credited with having forced down four more.

The citation for his Distinguished Flying Cross summed it up: “This officer has carried out some forty low flying raids on hostile troops, aerodromes, etc. and has taken part in numerous offensive patrols... In all these operations he has shown exceptional initiative and dash, never hesitating to lead his formation against overwhelming odds, nor shrinking from incurring personal danger.”

After his death, his close friend Stanford Howard wrote that Baker was “utterly fearless” and that he took new pilots under his wing and did everything he could to make sure they were safe during operations. “His machine could be seen darting here and there, always to the help of those in difficulties,” he wrote. “He met his death in the defence of others … fighting to the last.”

He was, Howard added, “the most gallant airman that left these his native shores.”

Baker's story was told in a Last Post Ceremony at the Memorial.

Baker’s mother, Annie, donated a copy of her son’s letters and airman’s log to the Memorial in 1928. She wrote to the then director: “It is a record of wonderful deeds and one of my most cherished possessions.”

The letters were one of the earliest donations to the National Collection and were used by Charles Bean in writing the Official History of the First World War.

“He was horribly brave,” Kelly said. “And he was never going to shirk a fight ... He went into that last fight knowing the numbers were overwhelming.

“It was a pretty devastating, last day of action for the squadron.

“To have survived so much of the war, and to die in the last action: you just think, why?

“His poor mother. She’s already had to bury her husband and to lose her son as well ... He was 11 years old when his dad died and she brought him and his siblings up by herself.

“It’s a hell of a thing to bury a husband, but then to lose her son as well, it’s pretty devastating.

“He was only 21, just a boy, but he’d already done so much.

“Who knows what he would have achieved if he’d made it home.”