The silent soldiers of Naours

Thomas Charters Forbes was killed in action in October 1917. Photo: Courtesy the family of Thomas Charters Forbes

It was just before Christmas, during the bitterly cold winter of 1916, when Australian Gunner Thomas Charters Forbes etched his name into the walls of a chalky limestone cave in northern France.

Less than a year later, Forbes was dead. The 22-year-old clerk from Melbourne was killed in action in October 1917 while serving with the 4th Australian Field Artillery Brigade on the Western Front.

More than a century later, his name is one of the thousands discovered etched into the walls of the subterranean city of Naours, a vast underground system of caves and tunnels beneath the plateau of Picardy, just a few kilometres behind the lines, near the French village of Vignacourt.

Since the discovery of an immense collection of glass plate negatives in the attic of a French farmhouse, the name Vignacourt has become synonymous with the extraordinary collection of poignant soldier portraits known as the Lost Diggers of Vignacourt.

Vignacourt was a day’s march from the front line, a place where thousands of Allied troops were sent for respite, away from the carnage of the trenches. It was an opportunity for troops to sleep, have their clothes laundered, visit cafes and estaminets, and take in the local sights.

Naours was a popular place for soldiers to visit during the war. It was discovered by locals in the 3rd century and used as a hiding place for villagers and their livestock during wars and troubles, right through until the 17th century.

The caves and passageways then fell into obscurity and were largely forgotten until they were rediscovered by a local abbot in the late 1800s. They became a popular local tourist attraction and were visited by thousands of Allied troops during the war.

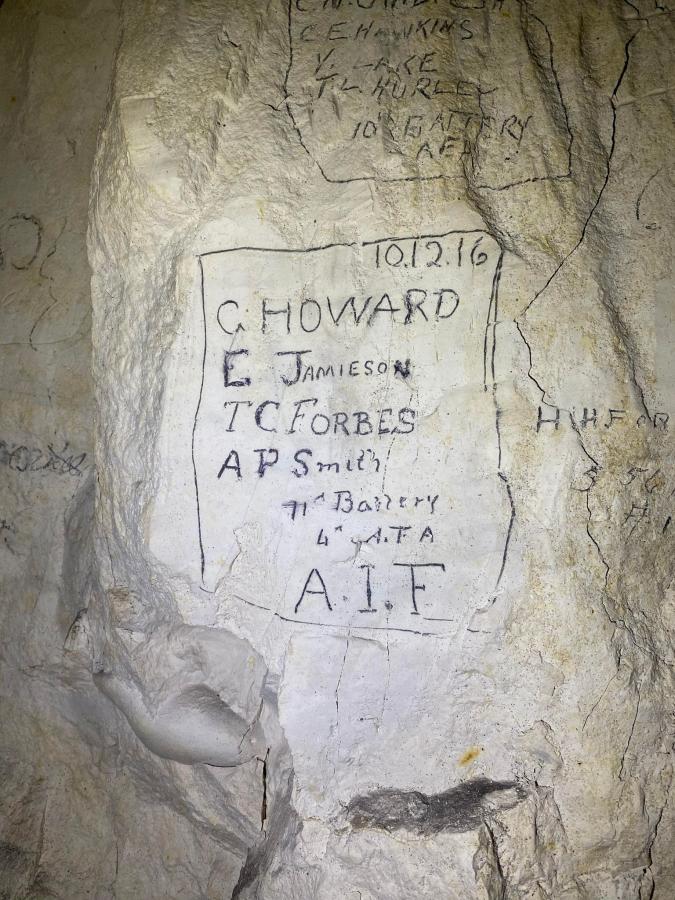

Today, the caves and tunnels contain more than 3,000 examples of graffiti from the Great War. It is the largest known collection of inscriptions drawn by First World War soldiers on the Western Front.

But they were forgotten until they were rediscovered by French archaeologist Gilles Prilaux in 2014.

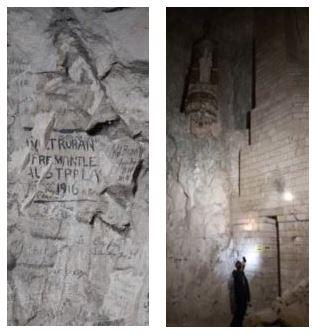

Thomas Charters Forbes and his mates etched their names into the wall more than 100 years ago. Photo: Courtesy Emily Hyles

Australian War Memorial curator Emily Hyles has been working to discover the stories behind some of the Australian inscriptions.

She first visited the caves in October 2022 and was fascinated by what she found.

“It was quite serendipitous, really,” Hyles said.

“I’d studied the Western Front for over 10 years, but I’d never been, so to see the places I’d read about, learned about, and been consumed thinking about was just amazing.

“We were visiting various sites on the Western Front and we went to Vignacourt to see the farmhouse where they found the portraits of the Lost Diggers, but it was All Saints’ Day, and so the farmhouse was closed.

“It was really cold, so we jumped in the car, and [my husband] Michael said: ‘I know where I’m going to take you.’

“It was just a 10-minute drive from Vignacourt, and I saw a sign that said Cité Souterraine, so I knew it was something underground, but I didn't know exactly what.

“It turned out to be this extensive cave system which had been used since medieval times.

“It was initially a quarry, and while they were quarrying, they discovered this huge natural cave system, which they used as a shelter for centuries, to hide from marauding armies during invasions.

“The whole village could move down there with their livestock. Then in the late 1800s, the local priest rediscovered them, and they became quite the tourist attraction.”

An Australian soldier etched this image of a digger in his slouch hat. Photo: Courtesy Emily Hyles

Emily and her husband Michael at Naours. Photo: Courtesy Emily Hyles

The complex of caves and tunnels stretches for three kilometres and is about 30 metres underground. It was dug out by hand, and at its peak, there were 28 galleries and 300 rooms. It was occupied from the Middle Ages until the 17th century and was home to about 3,000 locals who sheltered underground there during the destructive Thirty Years’ War, to hide from the armies that were crossing northern France.

As time went by, the caves and underground passages were closed and largely forgotten until they were rediscovered by Abbott Danicourt in 1887.

They became a popular place for Allied soldiers to visit during the First World War, and for a small fee, men could walk the passages and chambers, and learn about the history of the caves. The first Australian soldiers arrived at Naours as tourists in July 1916.

“They had English-speaking guides to show the men the caves,” Hyles said. “And the first AIF being what it was, they left their mark.”

It’s estimated there are some 2,000 Australian names etched into the walls of the tunnels and caves. They appear alongside the names of soldiers from Britain, France, North Africa, New Zealand and America. Some even included their rank, regimental number, battalion, and home town.

“French archaeologist Gilles Prilaux discovered this massive concentration of names about 10 years ago,” Hyles said.

“He was down in the caves doing some archaeological study on medieval artefacts when he found them. They look like they've been written in pencil, but they’ve actually been etched into the chalk with a pen knife, and then pencilled over, so they look as fresh as if they’d been done yesterday.

“There’s dozens and dozens and dozens of chambers, just packed with names.

“Some are dated. Some have little messages. And there's even one with a little drawing of a digger in a slouch hat. It’s unmistakeably Australian. And I just got so excited when I saw it.

“I was jotting down every name I could find that was obviously Australian, and then when we came out of the caves, this lovely woman at the tourist desk said, ‘Oh, Australians!’

“And then she took us into this little chamber that had even more Australian names etched into the walls.”

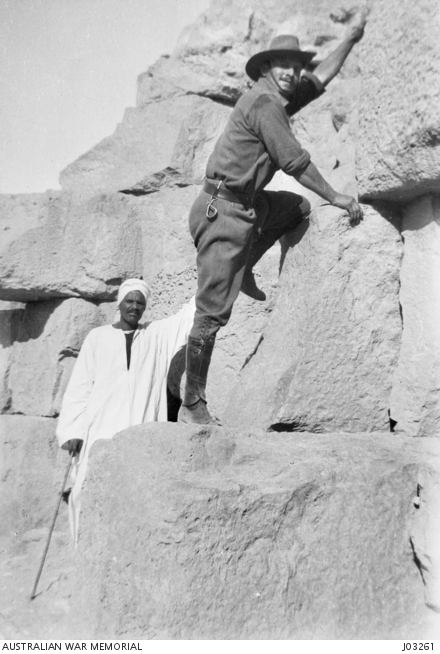

Informal portrait of 875 Driver Arthur Edward Attwell, 2nd Field Artillery Brigade, at the foot of the Cheops Pyramid prior to climbing it. He was later promoted to the rank of Bombardier. He was killed in action on 11 October 1917.

Determined to learn more, Hyles began to research the stories behind the names.

“When I got back to Canberra with my notebook of Aussie names, I started looking at the men and at our holdings in the National Collection,” Hyles said.

“One man, Archibald Arnott, survived the First World War, but died during the Second, and so he is listed on the Roll of Honour. Another, Driver Arthur Attwell, was killed in action in 1917, and we actually have a portrait of him in Egypt, with his foot on a pyramid.

During her research, Hyles has found everything from medals, caps and tunics, to portraits, photographs and even scrapbooks. They all belonged to Australian soldiers who etched their names into the walls of the caves at Naours more than a century ago.

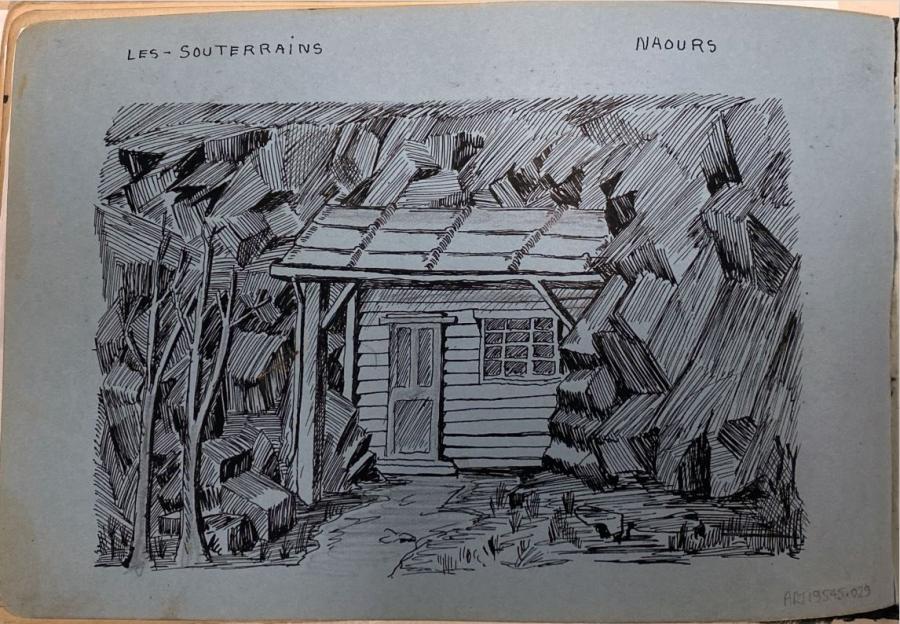

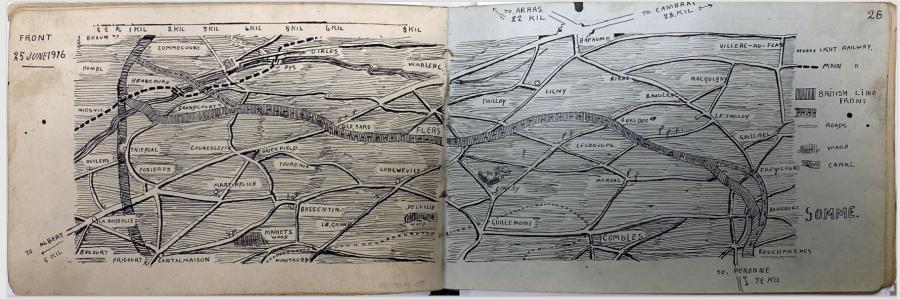

“The Memorial even has a couple of diaries that belonged to men who visited there,” Hyles said. “But the Eureka moment for me was finding this little album produced by Sapper James Stewart. It's a 47-page album of drawings that he did of army and civilian life. He's drawn the entrance to the caves at Naours as well as a map. And it’s all sitting in his sketchbook in our art store.”

In the meantime, Hyles continues her research, putting faces to the names. Thomas Charters Forbes was one of the first name she collected.

“It’s a passion project for me,” she said.

“And Thomas Charters Forbes was one of the names I jotted down in my notebook.

“He’s dated [his inscription] as December 1916 and he's there with two of his friends from the Field Artillery Brigade.

“He was the second eldest of seven children and was born in Richmond [in Melbourne] in 1896. He’d joined the initial rush of men seeking to volunteer, but was rejected because of the state of his teeth. Then, after Australia suffered heavy losses during the first weeks on Gallipoli, he made a second attempt to enlist, and he was accepted on 7 July 1915.”

In May 1916, the 4th Field Artillery Brigade was involved in constant heavy action against German positions, about 80 kilometres south of Sausage Valley, near the ruined village of Pozières. Thomas went on to serve during the bitter fighting at Bullecourt, Messines Ridge, Menin Road and Polygon Wood. He was killed in Belgium on 2 October 1917.

Australian soldiers of the 12th Battalion resting in a village street at Naours in July 1916.

Today, his remains lie at Reninghelst New Military Cemetery in Belgium, beneath the inscription chosen by his family: “For him hath dawned the perfect day.”

His story was told recently at a Last Post Ceremony at the Memorial. Hyles was the master of ceremonies. She was able to share photographs of Thomas’s inscription with his family.

“It’s a real privilege to be a part of these ceremonies,” Hyles said.

“We know he visited these caves because he left his mark there.

“It's just incredible, knowing these caves saw the footfall of all these Australians. Just knowing they walked there is really poignant, especially when you realise how many of these men died and didn’t make it home.

“The scale of loss on the Western Front in France and Belgium during the First World War was unimaginable. When I was down there in the caves, my heart was actually pounding ... The concentration of autographs is so thick, it’s overwhelming.

“There’s just so many of them. They look like they've been done yesterday. And it just goes on and on and on.

“There’s a real poignancy, especially when you read the names of those who died and don’t have a final resting place.

“They’ve left their tangible mark there in these caves... It fills a tiny gap in their movements and shows that they lived and that they were there.

“It makes it all come alive.”