Remembering Thomas Samuels

Warning: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people please be advised that the following article contains the names of deceased people. It also includes examples of racist and offensive language that were in use at the time.

Thomas Samuels wanted nothing more than to serve his country.

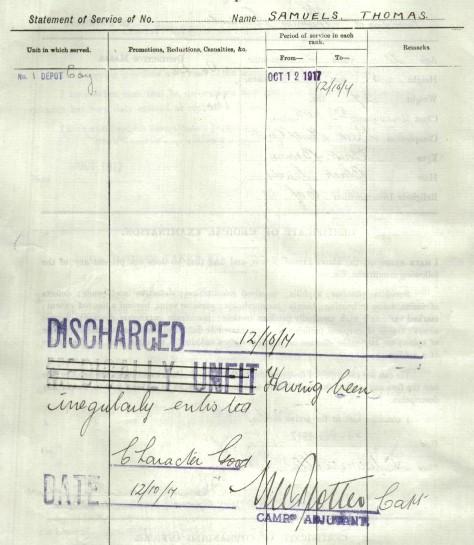

He enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force on 3 October 1917, was allotted to the No. 1 Depot Company on the 12th, and discharged that same day.

The reason: Thomas Samuels was Indigenous.

His Aboriginal heritage was then listed as a “disease” on his discharge papers.

He is one of more than 1,100 Indigenous Australians known to have enlisted or attempted to enlist during the First World War, despite restrictions preventing them from doing so.

For Michael Bell, the Indigenous Liaison Officer at the Australian War Memorial, Samuels’ story is all too familiar.

A proud Ngunnawal/Gomeroi man, Bell has been researching the military service of people of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent, and is working to identify Indigenous Australians who have served or are currently serving.

He said Samuels’ story was a powerful reminder of the added restrictions and the racism that Aboriginal people faced as they fought to serve their country, a country that rejected them, solely based on the colour of their skin.

Image: National Archives of Australia

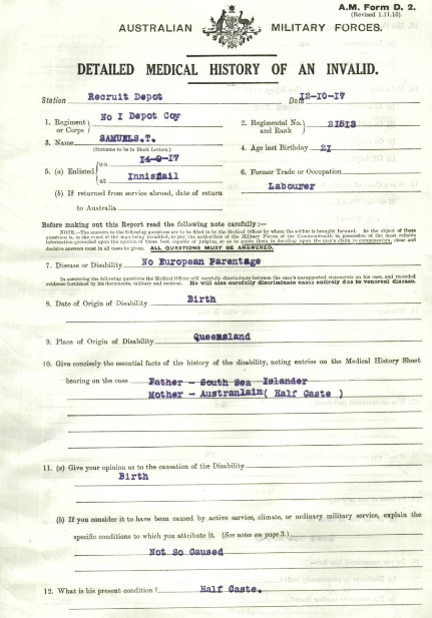

The son of a South Sea Islander father and an Aboriginal mother, Thomas Samuels was born in Innisfail on 15 July 1896 and working as a labourer in far north Queensland when he tried to enlist during the war.

The 1903 Defence Act, which was amended in 1909, had exempted people who were not “substantially of European origin or descent” from enlisting. But in 1917, after the first conscription referendum was defeated, and with large numbers of Australian casualties in Europe and the need for more manpower due to the ongoing war of attrition in the trenches of the Western Front, Military Order 200 was issued. It stated “half-caste” Aboriginal men could enlist in the AIF, provided the examining medical officers were satisfied one of the parents was of European origin. All previous instructions on the subject were to be cancelled.

“Thomas Samuels was 21 years old when he volunteered in October 1917,” Bell said.

“He was five foot eight and half, weighed 127 pounds, and had a chest expansion of 32 and a half to 34 and a half inches, but his complexion was listed as dark.

“That’s at a time just after Military Order 200 came in, and he is discharged that same day.

“It’s often referred to as the ‘half-caste law’, or the ‘half-caste order’, and Thomas Samuels is denied because he doesn’t have enough European heritage.

“He’s described as a ‘half-caste’ with dark brown eyes and black curly hair. And then they went to pains to say he wasn’t discharged ‘medically unfit’ because they put four lines through that reference in his records.”

Instead, Samuels was listed as having been ‘irregularly enlisted’. His discharge was then processed under the title, Detailed Medical History of an Invalid.

“It’s the only form the medical officers had available to them,” Bell said. “And on that form they list his Aboriginality as a ‘disease’.

“The ‘disease’ was from birth and the cause of the ‘disease’ was that he had a South Sea Islander father and a ‘half-caste’ Australian Aboriginal mother.

“The ‘disease’ was ‘insufficient European parentage’, but rather than just saying he was discharged, good behaviour, or that he was irregularly enlisted, the medical practitioners decided to process his discharge as an ‘invalid’ and listed his Aboriginality, or the colour of his skin, as a ‘disease’.

“The ‘disease’ was permanent and that, to me, reflects the thinking of the day.

“They’ve rejected a volunteer – a healthy, fit young man, in any other sense of the word – and then they’ve processed his discharge as an ‘invalid’ because it was considered a ‘disease’ to be Aboriginal in Queensland.

“And that’s from our medical practitioners... the Medical Board at Innisfail. And so a fit, healthy young man is denied the opportunity to serve. The only issue with him is that the doctors considered him too dark and he didn’t have ‘sufficient European parentage’.

Images: National Archives of Australia

“That’s all we know about Thomas Samuels.

“Very little, other than what is on his attestation papers, is known about him or his life after the war.

“We don’t have any other information about him, other than what we know from his first and only contact with the military authorities, during what appears to have been his first and only attempt to enlist.

“Not much else is known about him. We can’t track him anywhere. And so we don’t know what happened to him.

“But I highlight Thomas Samuel’s case because of the atrocious way in which the authorities treated his application.

“If I had been treated that way, I don’t know that I would have wanted to defend a country that had treated me so despicably.

“There’s absolutely no reason for his denial of service, other than being too dark.”

Sadly, Samuels’ story was not unusual.

“Our research shows that this wasn’t a one off, or isolated case; and it wasn’t worse or better in one state or another: it was across the board,” Bell said.

“Of the just over 260 Aboriginal men we’ve found so far who were rejected, I estimate that about 85 per cent of them were rejected because of race.

“That’s quite a number, and that’s reflected in the records, right across the board. ‘Deficient physique, a half-caste Aboriginal.’ ‘Physique is too low for military service.’ ‘Aboriginal full blood.’ ‘Too full-blooded for the AIF.’ These are direct quotes from the discharge certificates of these men and women during the First World War.

“Those types of words are used to reject our men, and there are countless cases in the records where that rejection is based on race – in accordance with the 1903 Defence Act that you had to be of substantial European heritage or origin.

“Despite Military Order 200 coming into place in March 1917, the rejection rate of our men was still fairly high, based on the colour of their skin.

“And yet, they still tried to enlist all the time. And some of them made multiple attempts.

“And that’s what we want to talk about: the additional hurdles that Aboriginal men faced to enlist, and the treatment of our men at the hands of the authorities in relation to their race and their identity, and their willingness to still enlist; some of them taking two or three goes to find an authority that would allow them to go and fight for their country, a country where they weren’t actually entitled to the rights that they were fighting for.

“And that’s why these stories are so important.

“It’s about the fight within the fight and about giving people their dignity back.”

Michael Bell is the Indigenous Liaison Officer at the Australian War Memorial. A Ngunnawal/Gomeroi man, he is trying to identify and research the extent of the contribution and service of any person of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent who served, or is currently serving, or has any military experience and/or contributed to the war effort. Michael would like to get further details of the military history of all these people and their families. He can be contacted via Michael.Bell@awm.gov.au