'They were so brave'

James Holland in a photograph taken at Vignacourt. It features on the cover of the first edition of The lost diggers by Ross Coulthart.

Val Lehman starred as “Queen” Bea Smith in the Australian television show Prisoner, but to the award-winning actress, her grandfather was a star.

James Holland, who fought on Gallipoli and the Western Front during the First World War, is one of the “Lost Diggers of Vignacourt”, whose photographs were discovered lying undisturbed in the attic of a French farmhouse almost a century later.

“He never spoke about the war,” Lehman said.

“His son … asked him a lot, but … he’d just shake his head, as if to say, no, no, I’m not going there … so I don’t really know what effect it had on him or what his attitude to it was, but I’m sure he was very pleased to have survived it …

“He was a forward machine-gunner … He was buried alive twice, ended up with diabetes caused from shock, and actually lived until he was 81, so he did alright. He married three times, and outlived all of his wives.”

Lehman, who played the ultimate “top dog” in Prisoner in the late 1970s and early 1980s, was in Canberra to visit the National Film and Sound Archive to mark the 40th anniversary of the show going to air. She visited the Australian War Memorial to view photographs from Vignacourt and lay a wreath in memory of her grandfather and all those who served.

“They were so brave,” she said. “I can’t begin to imagine what it was like and what they lived through.”

Jim Holland served on Gallipoli and the Western Front. Photo: Courtesy Val Lehman

Jim, as he was known, was born in England in 1891 and immigrated to Australia in 1911.

“He had come to Australia from Crewe in Cheshire with his older brother Charles to work and see what was happening in this incredible, brave, new continent,” Lehman said.

“He went to Perth, Western Australia, and got a job with the railways, and then of course the war broke out, so he and his older brother immediately joined the AIF. His brother was first wave Gallipoli, but James had hurt his foot, so he didn’t get in until the second wave.

“I think Gallipoli was pretty horrendous for him … He was one of the very, very last to leave. Having worked on the railways with a lot of explosives, he was there setting timed explosives to fool the Turks that the Australians were still there.

“He went straight from there to France, to Vignacourt, where he was billeted until he was sent to the trenches, and he survived that as well, and so did his brother.”

Jim Holland never spoke about the war. Photo: Courtesy Val Lehman

It was at Vignacourt that Lehman’s grandfather became friends with Louis and Antoinette Thuillier, an enterprising young couple who photographed thousands of troops as they passed through on their way to and from the Somme battlefields.

Captured on glass, printed onto postcards and then mailed home, their photographs helped soldiers maintain a fragile link with loved ones in Australia and provided a welcome distraction from the horrors of the Western Front.

Today, the collection of 4,000 glass-plate negatives, which was rediscovered in 2011, is considered one of the most precious visual records of the service and sacrifice of Australian soldiers in the First World War.

How it came to light nearly a century after the war ended is a tribute to the detective work of journalists and Memorial historians who pieced together information from photographs that had appeared throughout France and tracked down one of the Thuilliers’ descendants, Madame Henriette Crognier, who was still living in Vignacourt and knew where the collection was stored.

She insisted the collection be taken back to Australia for restoration, “pour les Australiens!”, and in 2012 more than 800 glass-plate negatives were donated to the Memorial by its chairman, Kerry Stokes.

The men became known as the “Lost Diggers of Vignacourt” and featured in a touring exhibition called Remember me: the lost diggers of Vignacourt, as well as a book and television documentary.

Val Lehman viewing some of the Vignacourt images with curator Lauren Hewitt.

It was Lehman’s cousin, Judy Carroll, who first saw their grandfather’s photograph on the television. “She was the one who contacted me, and said, ‘Granddad’s photograph is all over Channel 7,’ and we checked it out, and indeed it was.”

Lehman’s grandfather had posed numerous times, the mud from the battlefields still on his boots.

“We’ve got a postcard from Granddad, and he talks about how he’s been working with a local couple who are photographers, and they’re great friends,” Lehman said. “His photograph was taken quite often, apparently, and he became very much their poster boy.”

Today, Jim’s photograph adorns the cover of the first edition of Ross Coulthart’s book, The lost diggers, and features on the wall of La Maison De Les Australiens in Vignacourt.

“It’s a great photo, and we’re so very proud,” Lehman said. “He was a good-looking boy… and it’s amazing they survived so long … It’s just extraordinary that all of a sudden these photographic plates emerge again. The fact that there now remains a record of so many of them that were perhaps lost, I think is rather wonderful.”

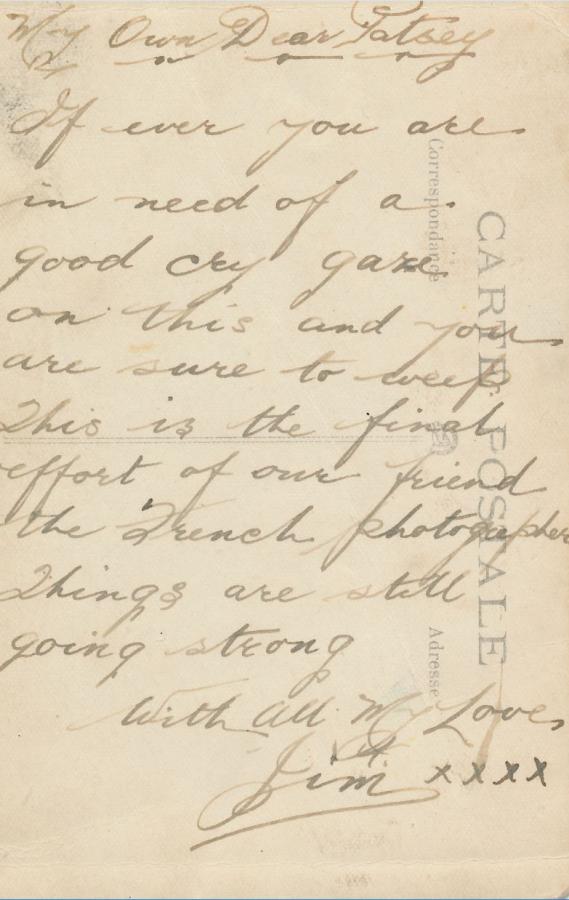

A postcard Jim sent from Vignacourt in August 1918. Photo: Courtesy Val Lehman

During the war, her grandfather’s sister, Mary, had feared the worst and wrote to authorities in November 1916 begging for news. “Can you give my any information regarding my two brothers who I have not heard from for the past three months,” she wrote. “I am very anxious.”

The Thuillers’ photographs would have been a welcome arrival.

“If ever you are in need of a good cry gaze on this and you are sure to weep,” Jim wrote on postcard from Vignacourt in August 1918. “This is the final effort of our friend the French photographer. Things are still going strong. All my love, Jim xxxx.”

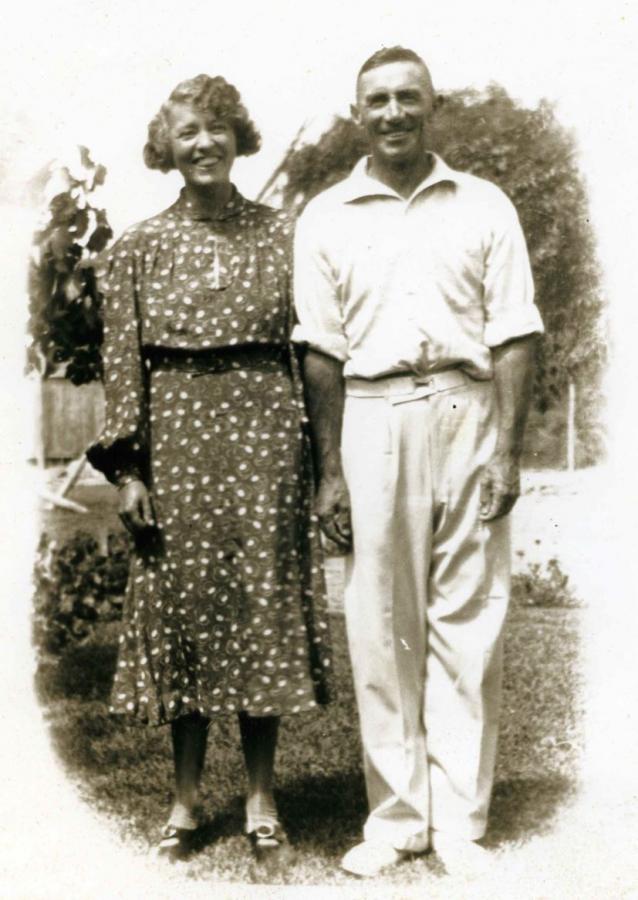

The postcard was addressed to “my own dear Patsey” and featured Jim’s photograph on the other side. “Patsey” was his pet name for Lehman’s grandmother, Dorothy Lightfoot, who had “lived down the road” from him in England. They had worked together in Crewe before Jim moved to Australia, and he stayed with her and her family while on leave. The two married in February 1919, and Dorothy followed Jim to Australia shortly afterwards on a ship for war brides.

Jim Holland with Lehman's grandmother Dorothy.

Dorothy’s younger brother Reg had been killed in France in February 1916 and Dorothy and Jim named their first son after him.

“He was only 19 when he was killed,” Lehman said. “We have a letter from him which talks about being up to his waste in mud in the trenches … It’s just awful, but then, all war is awful … There’s not nothing good about war. It doesn’t just affect the soldiers, it affects everybody, and I just cannot really believe that civilisation hasn’t progressed far enough to just not even consider it anymore. It’s just dreadful.”

For Lehman and her family, the rediscovery of the Vignacourt photographs almost a century after her grandfather served was particularly special. A copy of one of his photographs was presented to Jim’s two surviving children, Lehman’s mother, Kath Malta, and her twin brother Reg Holland, at their 90th birthday party, and they couldn’t have been happier.

“I’m very, very proud of my father,” Kath said at the time. “I’ve been very proud of the fact that he served in Gallipoli and then went through the Western Front. I mean, how could you not be proud of a man like that, and he was a wonderful father and marvellous husband.”

Val Lehman: “I can’t begin to imagine what it was like and what they lived through.”

Today, Lehman and her family remain extremely proud of their grandfather and are forever grateful that he and his brother made it home.

“It reminded me of how I feel, every Anzac Day, standing at a memorial as the sun rises at dawn and the bugler plays the last post, I cannot help but tear up myself,” Lehman told Ross Coulthart. “I always think about all those young men that didn’t return. And how very sad it is.”

The lost diggers by Ross Coulthart is available from the Memorial shop and online. Its publication coincided with the Memorial exhibition, Remember me: the lost diggers of Vignacourt, which opened in 2012 and toured nationally until 2018. To view the Thuillier collection, visit here.