Valour

Valour is a special human quality, usually demonstrated in the performance of extraordinary and unselfish deeds in the face of great peril. It is represented in a variety of words: bravery, boldness, courage, gallantry, and heroism. It can be observed in both peace and war. However, valour is particularly evident in wartime, where the risk to one's life in the service of others is more likely to be observed.

The story is told that when Queen Victoria visited wounded soldiers from the Crimea she was so moved by accounts of great courage that she instituted the Victoria Cross. Embossed on this highest award for bravery are the words "for valour". Inspiration at all levels can be derived from tales of great courage.

Medals are a symbolic recognition of valour, but they are not a measure of it. A hundred years after the VC was instituted another monarch, Queen Elizabeth II, reminded those at the special centenary parade that

beyond this gallant company of brave men [VC recipients] there is a multitude who have served their country well in war. Some of them may have performed unrecorded deeds of supreme merit for which they have no reward.

The official war historian Charles Bean admired men of valour and high moral character and wove their stories into his account of the Great War. He also found inspiration when observing the common soldiers' dogged endurance. After the battle of Pozières, fought in France in 1916, he wrote:

For an ordinary man, feeling as he would feel after Pozières, to go into it again in spite of his natural state of mind and do all they would do is a hundred times finer than the heroics that have been written about in the past.

Still, there was something special about those who stood out and whose work encouraged others to a higher level.

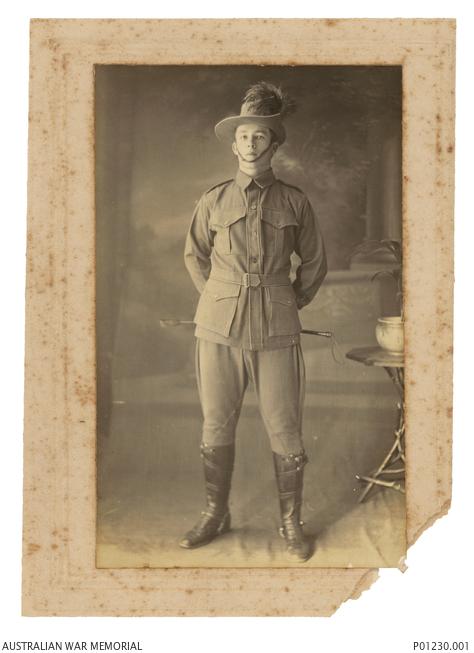

Studio portrait of 3347 Private David Emmett Coyne, 31st Battalion.

For soldiers, exposure to battle called forth many responses. Describing a German artillery shelling, Bean noted: "every man in the trench has that instant fear thrust upon his shoulder - I don't care how brave he is - with a crash that is physical pain and strain to withstand." The strain of battle was a most severe test. "In it, the mask we wear through life drops off," said Lord Moran, who wrote a famous study of men in war drawn from his experiences as an army medical officer. He added:

I can find little ... to support the comfortable creed that all men are heroes. A few men had the stuff of leadership in them, they were like rafts to which all of the rest of humanity clung for support and for hope.

Moran considered both courage and fear, but saw them not as opposite subjects. He saw that in battle fear is a normal human response and was present among even the bravest front-line troops: "Fear even when morbid is not cowardice." There were those who could put their natural fear aside and risk their lives for the support of others around them. The valour of these outstanding men and women was always admired and was sometimes legendary.

An Australian infantry officer, Captain George Mitchell, expressed in his own way the idea that war is a test: "Battle strips all masks and shams from every one, each having to stand naked to the gaze of his companions."

Fear experienced during battle was something Mitchell was qualified to talk about. He had won the Distinguished Conduct Medal at Bullecourt in 1917 and the Military Cross in March 1918. It was said that he led his platoon in "an absolutely fearless manner". Nevertheless, when addressing young officers of a new war in 1940, he said: "Fear grips you everywhere; constricting your throat, squeezing your heart. It is like a lump of ice in your stomach." It is at such times that men look for heroes and leaders, or for their own inner strength.

Captain Albert Jacka was one such man. He established himself as a national hero when he became the first Australian to win the Victoria Cross in the First World War. On that occasion, on Gallipoli, he made a bold counter-attack with rifle and bayonet against the enemy. But Jacka was remarkable in showing courage on numerous occasions. He would go on to be awarded the Military Cross and bar for brave work at Pozières in 1916 and at Bullecourt the following year. So strong was his influence within his 14th Battalion that it was unofficially known as "Jacka's Mob".

Captain Walter Gilchrist was a bold and natural leader killed in 1917 at Bullecourt, France. There he saw the Australian line beginning to crack. Going into the maelstrom, he was heard to say: "These men are alright. All they need is a leader." Charles Bean tells us what happened next:

None ... knew who their leader was, but for half an hour or more he would be seen, bareheaded, tunicless, in grey woollen cardigan, his curly hair ruffled with exertion, continually climbing out of the trench to throw bombs or to call to the men in the shell-holes, begging them to charge.

Gilchrist received no posthumous award for this remarkable bravery.

Among those acknowledged as heroes were some who would comfort and motivate others and spur them on. They could even affect the course of an action. Australians were proud to claim that if a leading officer or NCO became a casualty, there would always be someone there to step quickly into their place.

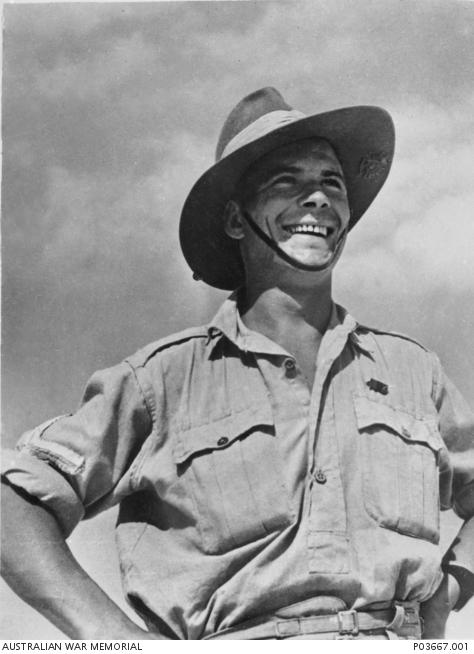

Outdoor portrait of SX7429 Corporal (Cpl) James Hinson DCM.

Captain Percy Cherry was an inspirational soldier. The only surviving officer of his company, he led his men in the clearing of a village in March 1917. Cherry's Victoria Cross citation says:

His leadership, coolness and bravery set a wonderful example to his men. He took charge of the situation and beat off the most resolute and heavy counter-attacks. Wounded ... he refused to leave his post and there remained, encouraging all to hold out at all costs, until ... this very gallant officer was killed.

Courage and leadership were also evident in Private George Cartwright's attack on an enemy machine-gun post during the advance on Péronne in 1918. His actions had "a most inspiring effect on the whole line, which immediately rushed forward". His award citation said: "Throughout the operation Private Cartwright displayed wonderful dash, grim determination and courage of the highest order".

Lieutenant Colonel Norman Marshal was renowned for his consistent bravery. Typically, at Villers-Bretonneux in 1918, "with total disregard of danger he passed up and down not only his own lines but the lines of the other battalions encouraging all ranks by his confident bearing, voice and action". It was said that he inspired "the courage and determination of his men". "In a tight corner", wrote Charles Bean, "the mere knowledge that Normal Marshal was in charge would give confidence to all Australians who were aware of the fact."

Similarly, Harry Murray had a powerful reputation as an outstanding hero. Even before the war, he had shown himself to be a mature and independent leader of men. He became the most highly decorated soldier in the Australian army, rising from the ranks to command a battalion. A fierce fighter, he was not a reckless hero, but rather a quiet and charismatic leader who believed in thorough training and discipline and possessed sound tactical skills. In the action for which he was awarded the Victoria Cross, "this gallant officer rallied his command and saved the situation by sheer valour".

But valour is not defined by physical strength or fighting ability. It is boldness or firmness in situations of great danger, usually in the support or protection of others. Two of Australia's most famous war heroes were non-combatants: John Simpson Kirkpatrick, "the man with the donkey", who risked his life to rescued wounded men on Gallipoli, and "Weary" Dunlop, a medical officer who treated the prisoners of the Japanese during the construction of the notorious Burma-Thailand Railway.

Studio portrait of Captain George Meysey Hammond MC, MM.

Sir Albert Coates was another man of similar character. Coates served in both world wars, and in 1941 was a lieutenant colonel and senior surgeon to the AIF in Malaya. Taken prisoner by the Japanese and sent to the Burma-Thailand Railway, he worked tirelessly and at great risk to give comfort and support to the sick and dying. He became renowned for his courage, skill, wisdom, and dedication to others. After the war he resumed his distinguished medical career.

Sister Vivian Bullwinkel was one of the Australian nurses escaping from doomed Singapore when their ship was sunk in the Banka Strait. After some hours she struggled ashore with other survivors. The Japanese gathered together 22 nurses, ordered them into the sea, then machine-gunned them. Amazingly, Bullwinkel survived, only to be taken prisoner again 12 days later. With great fortitude and courage she endured a further three years of hard and brutal treatment before her eventual release.

Lieutenant Tom "Diver" Derrick, a man possessed of the highest valour, was seen by many as the embodiment of all the best characteristics attributed to the Australian digger. Tough, with a larrikin grin, he was also intelligent and thoughtful. Already holding the Distinguished Conduct Medal, he won the Victoria Cross at Sattelberg, New Guinea, in 1943. His exploits brought him to wide public attention. The news of his death on Tarakan Island the following year spread like a shock-wave. Within his division it seemed, as one soldier said, that "the whole war stopped".

In 1942, returning from a bombing raid, Pilot Officer Rawdon Middleton, who was badly wounded, flew his aircraft back to Britain and fought to allow his crew time to escape before he crashed into the sea and was killed. One of those he saved later wrote that his act was "an example of the unwritten law ... that a crew always endeavours to get back. It is also an example of another law - that a pilot must think of his crew before himself."

More than 20 years later, in Vietnam, in a similar act of self-sacrifice, Warrant Officer Kevin Wheatley stayed with a wounded mate rather than abandon him to the approaching enemy. Both men died. It was recorded that "his acts of heroism, determination and unflinching loyalty in the face of the enemy will always stand as examples of the true meaning of valour".

Bravery comes in many forms. Similarly, there are many types of individual who have demonstrated this quality. Those observed to have performed acts of the highest level seem to have little in common beyond their valour. Great bravery is not the natural accompaniment of rank, privilege, or education, nor is it the possession of those individuals of any particular religion, colour, creed, age, occupation, or sex.

Over the past century and a half great acts of valour have been performed in war by many of those Australian men and women serving in the army, the navy, and the air force, or in peacetime. The stories of their deeds inspire and create pride throughout the nation. Some stories endure to be told regularly, while others pass from memory and public attention. Yet it seems we still need heroes from which we can draw comfort, safety, and example, and so men and women of valour will continue to be sought, admired, and, where possible, acclaimed.