Vapour trails high in the sky

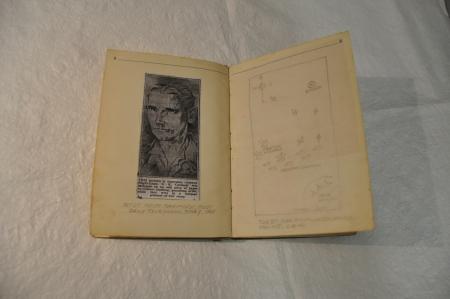

The visual content of prisoner of war Gilbert Docking’s wartime diary foreshadows an extraordinary post-war contribution to the arts. The moment I began to leaf through the pages, I was intrigued. Visually it was familiar, redolent of art school days and filling a journal with drawings, thoughts, quotes, photographs, captions, press clippings, and mementoes. Bold titling on an opening page reads “JUNE 13TH 1944, SHOT DOWN”. Overleaf is a newspaper cutting of a sketch, captioned “This portrait of Australian cricketer Flight-Lieut. D.K. Carmody was sketched on an odd piece of paper by Gilbert Docking, peacetime artist, while they were in a German prisoner-of-war camp”.

“Who was Gilbert Docking?” I wondered. Further research revealed he was the man who would, after the war, discover noted Australian artist Brett Whiteley and become an eminent curator and gallery director.

News clipping of Keith Carmody

Gilbert Docking (known as “Gil”) graduated from Melbourne Boys High in 1935 with a scholarship to study Industrial Design at the Royal Melbourne Technical Art School. By 1938 he had his first job as designer at a glass factory. This work, however, proved disillusioning. Rather than engaging in a creative opportunity, he primarily produced stencilled graphics for shower screens.

About this time, his family, who were strong Methodists, became increasingly disturbed by reports about Nazi Germany. Docking saw the Methodist church as an organisation working to improve social conditions against corruption and entered the training college in Kew, Melbourne, for Methodist Home Missionaries. As a 20-year-old newly-trained pastor, he served in the remote town of Swifts Creek in Eastern Victoria before moving to the Melbourne suburb of Bayswater.

But his arguments for peace couldn’t compete with the threat of war on Australian soil. On 9 October 1942 he enlisted, becoming a Flight Lieutenant with the RAAF.

Flight Lieutenant Gilbert Docking was posted to Australian Coastal Command Squadron 455, in Langham, Norfolk. On 13 June 1944 Docking was navigating a Beaufighter, piloted by Australian cricketer Keith Carmody, which was patrolling the English Channel. The aircraft was off the Dutch coast when it was hit. With engine failure, Carmody prepared to ditch, successfully carrying this manoeuvre out at 322 km/h. Carmody and Docking were thrown from the plane and spent the next 24 hours in a rubber dingy in the North Sea. After being picked up by the crew of a German motor torpedo boat, they were taken to the prisoner of war camp Stalag Luft III-A, located in Luckenwalde, on the border of Germany and Poland.

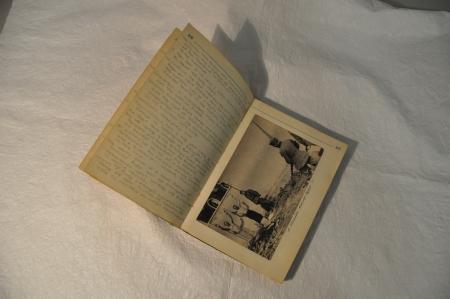

Docking and Carmody remained interned here until they were liberated by Russian forces in 1945. Docking’s diary of his experience is highly visual: detailed drawings illustrate written entries; personal captions contextualise photographs; cartoons create relief; and coupons, maps, diagrams clippings, and concert programs further document his experiences. Emotionally, the diary reflects stoicism; pages 41 to 46 describe the beginnings of liberation. Docking’s entry on 27 January 1945 reads

“The Russians are over the Oder” – This statement together with “The Russians are 40 miles east of Frankfurt–on-Oder” gives impetus to the belief that we will be relieved by Wednesday next. One fellow said “It looks like we’ll hear them tonight and see them tomorrow”.

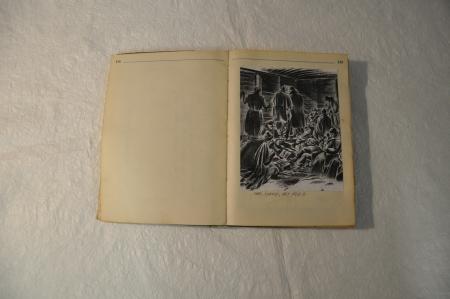

A German firing squad.

Over the next week Docking wrote daily, detailing the prisoners’ forced march from camp to Spremburg Railway station. His final written entry of 3 February reads,

Fortunately this is the last stage of our march to Spremburg Railway Station. My feet have packed up, but I can manage. All we notice is the bitumen road passing beneath our boots, and the bobbing packs on bowed shoulders all around. At midday we halted at a modern army barracks. An air raid at the same time was a diversion. Vapour trails high in the sky. The army gave us a good ration of barley glop, and we proceeded to Spremburg West where we entrained in cattle trucks. Locked in each of these strawless enclosed vans were 45 men. As usual the Germans had made no sanitary or water arrangements.

Prisoners of war huddled together

Docking’s entries are illustrated by his works and the works of others. While drawings on pages 33, 37, and 39, and images on grey toned pages are by Docking, the photographs are the work of fellow prisoner of war James Hill, who posted them to Docking in1946. Showing scenes at Ludenwalde, the photographs were shot on a camera that Hill took from the camp-guard quarters when the Germans fled the Russian army. Docking has captioned one of the photographs “Russian tanks arrive at Luckenwalde POW camp with women soldiers in tank crews”. Reflecting on the last days of war, Docking wrote, “at last we could hear the rumbles of cannon as the Russian Red Army tanks rapidly advanced into our compound, stopped to make contact and amuse us by dancing and clapping, then racing on to Berlin 30 miles away”.

After the war Docking returned to the art world, enrolling to study Fine Arts and Theology at Queen’s College, University of Melbourne. In 1951 he became Education Officer at the National Gallery of Victoria. Touring Victoria with travelling exhibitions, he curated exhibitions in 50 towns. The outstanding success of these travelling shows led to the establishment of regional art galleries across Victoria, and Docking was invited to establish the Newcastle Art Gallery. The gallery first opened in 1957 in the War Memorial Cultural Centre in Newcastle’s CBD. In 1959 Docking identified the young Brett Whiteley as a major new talent, and acquired Whiteley’s first purchased work, Autumn abstract, for the collection. Docking also persuaded the gallery to buy a Fred Williams and a William Dobell. Docking directed the Newcastle Art Gallery for seven years. When he left, the gallery was recognised as the leading provincial art gallery in Australia.

In 1965 Docking left Newcastle for New Zealand, where he was appointed Director of the Auckland Art Gallery. In 1972 he moved to Sydney, to the Art Gallery of NSW. He worked as the Senior Education Officer, and in 1974 became the Deputy Director.

He retired in 1982 and focused on curating the works of Sheila (Shay) Lawson, his wife. The couple set up two foundations, one in Melbourne and one in Sydney, to help young artists. In 2014 Gil was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia (OAM), for service to the arts.

Gilbert Docking died on 17 November 2015, aged 96. He was seated in his favourite chair, at home in Paddington.