'We were pretty lucky'

Vern Roberts has fond memories of working on the Liberator bombers during the Second World War. Photo: Courtesy Vern Roberts

Vern Roberts says his legs are “a bit tottery” these days and his “hearing is gone”. But there’s nothing wrong with his memory.

The 98-year-old was an airframe fitter in the Royal Australian Air Force during the Second World War.

He was guarding a Liberator bomber on the island of Morotai when he learnt the war was over.

It was nearly 80 years ago now, but Vern still remembers it as if it was yesterday.

“Oh, vividly,” he said, from his home in Victoria.

“Each aircraft had to have a guard on it during the night-time.

“Whether you were technicians like we were, or guards, we all had to be given a rifle, and of a night-time, the duty officer would drop you off at each aircraft along the strip to guard it, just in case, because there were Japanese on the island still.

“This particular night, I was on guard, and at about midnight it was, I could hear a lot of guns firing, and I wasn’t very happy about that because I thought, ‘Geez, the Japs have broken out ... and they could be heading this way.’

“It wasn’t long after that the duty officer come driving up the airstrip in his little jeep. He pulled up at each of the aircraft and he said, ‘It’s alright fellas. Don’t worry about the firing. The war’s over. Japan has surrendered, and the guys down at the camp are firing off their guns.’

“So that relieved me quite a bit. But he said, ‘I can’t take you back yet, you’ll have to wait till morning.’

“And so here we are, on our own, on each aircraft. And after all that, after all those six years of war, it was over – thank God.”

Vern with his mother in Footscray. Photo: Courtesy Vern Roberts

Ready for dinner at the mess, Fenton, 1944. Photo: Courtesy Vern Roberts

A lifelong Bulldogs supporter, Vernon Roberts was born in the inner west suburb of Footscray in Melbourne in October 1924. His parents had emigrated from Guernsey in the Channel Islands with his older sister Winifred in November 1919.

Vern left school in 1938 and was working as an apprentice at a printing firm in the city when the Second World War began. His family still had relatives living in Guernsey when the Channel Islands were occupied by the Germans in June 1940.

“I was only 15 when the war in Europe broke out,” Vern said.

“So by the time I was 18, it had been going for three years, and then I was mixed up in it myself.

“Time just goes on, and you don’t realise that when you are a kid at 15. And the next thing you’re 18 and you’re part of the war effort.

“I’m not patting myself on the back or anything like that, but we were only kids.

“It was a great adventure in those days ...

“And before I knew where I was, I was called up. “I thought, ‘Oh, well, aeroplanes will do me,’ so I joined the air force ... learning all about aeroplanes and the theory of flight, hydraulics, and goodness knows what.”

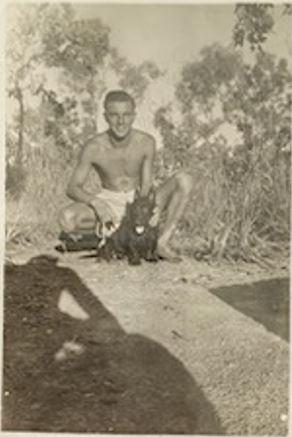

Vern and his mate Vern Harvey with a baby kangaroo at Fenton near Darwin in 1944.

Vern with Scotty, one of their mascots at Fenton, 1944. Photo: Courtesy Vern Roberts

After training at Shepparton in north-east Victoria, and then Adelaide, Vern was posted to new RAAF base at East Sale in Gippsland.

“I spent the next eight months working on Lockheed Hudson aircraft and Airspeed Oxfords,” Vern said.

“The aircraft were used to train aircrew for operational duties.

“And from there, some of us, including myself, were posted to Tocumwal.

“This was the RAAF Operational Training Unit where pilots, radio operators and air gunners were converted onto the B-24 Liberator bomber.

“They had only just taken delivery of the Liberator bombers ... so we did a crash course on Liberators and before I knew where I was I was being sent up to the Northern Territory. And our aircraft were bombing right across the Timor Sea.”

Wood chopping at Fenton, near Darwin, in 1944. Photo: Courtesy Vern Roberts

Vern was posted to No. 24 Squadron, the squadron he would remain with until the end of the war.

“In December 1944, we travelled to Darwin, where we boarded two Liberty ships ... the SS Louis Arguello and the Cleveland Forbes,” Vern said.

“At the time of boarding, our destination was unknown.

“It turned out to be a little island called Moratai, which was up in the far north of New Guinea, not far from Borneo.

“We were escorted by a destroyer ... and we travelled right around from Darwin to Port Moresby and then all the way up the north coast of New Guinea.

“Liberty ships in those days were just cargo carriers, but they used them for carting troops around too.

“They were only 12,000 ton ... so there wasn’t very much accommodation on them – none at all – and each ship carried about 1,200 airmen.

“We travelled okay, but in those days we were only 18 or 19 year olds, so we weren’t too worried ...

“We had a destroyer as an escort ... and despite there being a real risk of an enemy submarine spotting us ... we got to Morotai without any trouble.”

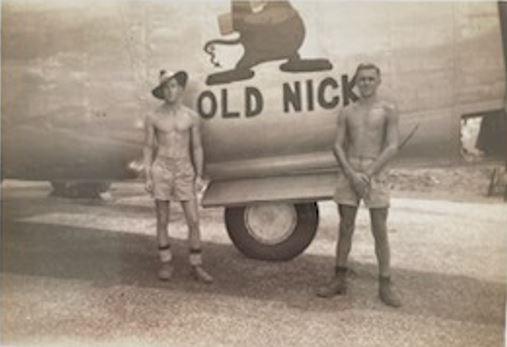

Vern, right, with Gordon Roscoe and 'Old Nick', a B24 Liberator which later crashed, at Fenton in 1944. Photo: Courtesy Vern Roberts

Over the next few months, the Liberator bombers were kept busy, carrying out raids, day and night, on Borneo and the surrounding islands.

“Morotai is a tourist island now, but during the war years, Morotai was held by the Japanese,” Vern said.

“[It] was taken by the Americans [in September 1944] and they used Morotai as a strategic point to regain the Philippines ...

“The next thing then was to take Borneo.

“Our aircraft – American as well as Australian – played havoc with the Japanese on bombing raids, so it was a pretty important little island in those days, but it was full of jungle, and it rained a lot, and there was plenty of mud and such, and it was not an easy island to live on, I tell you ...

“Our aircraft were bombing from there to Balikpapan and Tarakan ... and so my job was to look after the airframe and the hydraulics.

“It was a specialist job, and the pilots and the aircrew relied on the people who looked after the aircraft and kept it flying.”

Vern witnessed the Australian General Thomas Blamey accepting the surrender of the Japanese Second Army at Morotai on 9 September 1945. Photo: Courtesy Vern Roberts

He will never forget how he felt when the war was over.

“The 15th of August 1945 was greeted with a great deal of relief from all of us,” Vern said.

“The Japanese had surrendered.

“And after six years of war ... the war was over and that was the end of that.

“We were very elated naturally ... but I never got home until December.”

Vern was there to witness the Australian General Thomas Blamey accepting the surrender of the Japanese Second Army at Morotai on 9 September 1945.

“I was present at the signing of the instrument of surrender, and I can remember, I had my little camera with me that my mother had given me before I left to go up north,” he said.

“There were thousands of troops there witnessing it and ... that was an historical part of my life.

“They assembled us all around this sports ground and they flew the Japanese generals in and then General Blamey and his other officers signed the surrender.

“The mood of the people there was pretty tense because we knew that it was an occasion where we’d won the war and we knew we were all going to go back to our civilian lives ...

“Our aircraft were then used to transport our nurses, prisoners of war, and thousands of troops back down south ... to the capital cities like Brisbane and Sydney and Melbourne.

“We were home for Christmas 1945 ... And Mum and Dad were probably so pleased they got their son back home safe and sound.

“And then it was time to pick up civilian life where we had left off back in 1942.

“So I went back to my trade and finished my apprenticeship ... and that was it.”

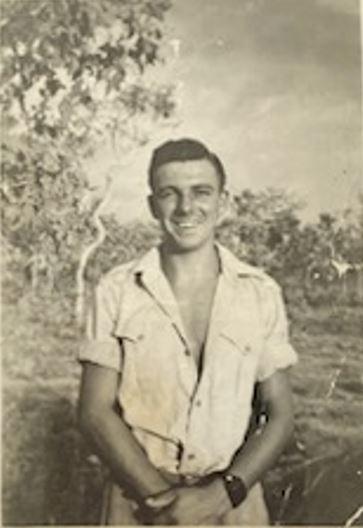

Vern, aged 20, at Fenton. Photo; Courtesy Vern Roberts

Vern with his pet monkey, Charlie, at Morotai. Photo: Courtesy Vern Roberts.

Vern went on to work at the Commonwealth Bank Note Printing facility in Craigieburn and bought a taxi licence, driving taxis in and around Melbourne for almost 30 years.

He met his wife Gwen after the war and they were married in Williamstown in January 1949.

“All my mates were kicking their heels up,” Vern said. “And so I started to go to the dances. And it wasn’t long after that that I met the love of my life. It changed my life completely and I’m still in the little house that we had built when we were first married.”

They had two children, Brian and Glenda, and were married for 69 years when Gwen died at the age of 93 in April 2018. She was his “greatest source of inspiration and support” in everything he set out to achieve.

“We were pretty lucky in a way,” Vern said. “And I’m still soldiering on.”

Vern, pictured, front row, third from left. Photo: Courtesy Vern Roberts

For the past 30 years, Vern has been involved in the restoration of a B-24 Liberator bomber at a Second World War hangar in Werribee, Victoria.

“They built 18,000 of them, and in the world today, there is only about 10 left,” Vern said.

“When I first walked in, they had it in the hangar. They had the fuselage and the wing and that’s about all. Some of it was found in New Guinea, and some of it was found in northern Australia, and when I walked in and saw this aircraft I thought, ‘By God, they’ll never ever put this together.’ That was 1996. And well, you walk in now and you’d think this aircraft could fly straight out of the hangar. You’d be astonished at how much work has been put into it... I used to say to people, it’s the biggest men’s shed in Australia.”

Today, Vern has a model of a Liberator bomber sitting on his dining room table at home. All these years after the war, it’s still his favourite aircraft.

Vern in uniform in 1943. Photo: Courtesy Vern Roberts

Each year, Vern marched at the Anzac Day services in Melbourne in memory of his mates and those who didn’t make it home.

“They didn’t all survive,” he said.

“When they’d fly over the islands where the Japs were, there was plenty of anti-aircraft fire. And of course, they’d get shot down by Zeroes as well.

“If they did, they had a crew of 11 on board, all Australians, all in the RAAF.

“You were pretty sad to lose 11 guys in one go. And that was rather hard to take.

“But that’s war for you. It’s terrible, and we don’t want that again.

“It’s only in the last couple of years that we’ve talked about this.

“The kids didn’t even know where I had been ... You just never talked about it, but in later years, people want to know a bit more about the history of it ...

“As I reflect on my life, there are two things, I believe, that are very important.

“The first is to be caring towards one’s parents and the second is to always have respect for other people. I hope that, through my example, my children and grandchildren have learnt this too.”