'I've been blessed'

Victoria Margaret Watt at 92. She was born on 11 November 1918. Photo: Courtesy Murray Watt

As the world pauses to commemorate the centenary of the armistice that ended the First World War on Remembrance Day 2018, Victoria Watt will celebrate her 100th birthday with family and friends.

Mrs Watt was born Victoria Margaret Sullivan in Mitchell, Queensland, on 11 November 1918, the day the armistice was signed.

“I believe my father celebrated for a week,” she said with a laugh.

“My mother was in labour for a day or so, and finally the matron said to one of the nurses, ‘Quick, go and tell Dr Shannessy that Mrs Sullivan needs his help,’ so the nurse ran across Dublin Street, and knocked on the doctor’s door.”

But the doctor was nowhere to be found. He had left early that morning and his wife didn’t know where he was.

A group of women and children rejoicing in a street in Sydney at the signing of the Armistice.

“Well, he was with hundreds of others banging on kerosene tins because the war was over,” Mrs Watt said. “So the matron had to help my mother deliver me, and I was a 12-pound baby.”

Her parents, William and Elizabeth, named her Victoria in honour of the allied victory.

“There was another lady who had had a baby girl four or five days before my birth so my mother received a nicely written note on nice stationery: ‘Dear Mrs Sullivan. Congratulations on the birth of your daughter … I suggest you name her Peace or Dardanelles. Kind regards, Mae O’Neil.’

“My mother said when she got over the feeling of horror and disgust, she got her nice stationery out and wrote: ‘Dear Mrs O’Neil. Thank you, my dear, for your best wishes, [but] my husband and I want our daughter to love us, not hate us. We are naming her Victoria, which is Latin for victory. Kind regards, Elizabeth Sullivan.’

“Years afterwards, I said: ‘Thank you, Mummy, I certainly wouldn’t have loved you if you’d called me Peace or Dardanelles…”

A crowd in Martin Place, central Sydney, celebrate the news of the signing of the armistice.

Mrs Watt laughs as she shares the story ahead of her birthday celebrations.

“I didn’t think that I would still be around after 100 years,” she said smiling. “I’ve had a few close shaves in those 100 years, and I’m still here … but I really did not think I would still be here.”

She nearly died when she was just 12 days old.

“My father drove up to Mitchell in the wagonette with his two trusted ponies to pick my mother and his baby girl up,” Mrs Watt said. “He was heading back to towards the homestead, my future home, and something – my father said it was a big fly – bit one of the ponies and it bolted.

“It seemed as if the wagonette was going to tip over so my mother wrapped me up tightly in a shawl, waited for a clear patch, because there was scrub everywhere, and threw me over [the side] as she bolted over the wheel. She was screaming. She thought she’d killed her baby, and there I was sucking my thumb…”

A large crowd gathered in Martin Place, Sydney, to celebrate Armistice Day. A replica sailing ship, festooned with lights has been set up like a stage for dignitaries to address the crown from.

When she was four, she was bitten by a redback spider at home on the family farm.

“I survived that too,” Mrs Watt said, laughing once more. “The lady my mother had working for her, she rather liked me, and I was late coming out for breakfast. My mother was in the hospital at the time … and all the workmen had gone, and it was really cold, so she said, ‘Darling, you can have your breakfast beside the stove,’ and as I walked around the stove, I must have brushed against it, and it bit me several times on the wrist.”

With her mother in hospital, it was her father who came to her aid.

“It wouldn’t matter if you broke your toe,” she said, laughing once more. “If my mother wasn’t home, he would give us a dose of castor oil, so there I was screaming with pain, and, yes, I was given a dose of castor oil. The doctor said to him, ‘Well, that’s one time that it was a good idea to give your little girl a dose of castor oil because it’s not advisable,’ but it worked.”

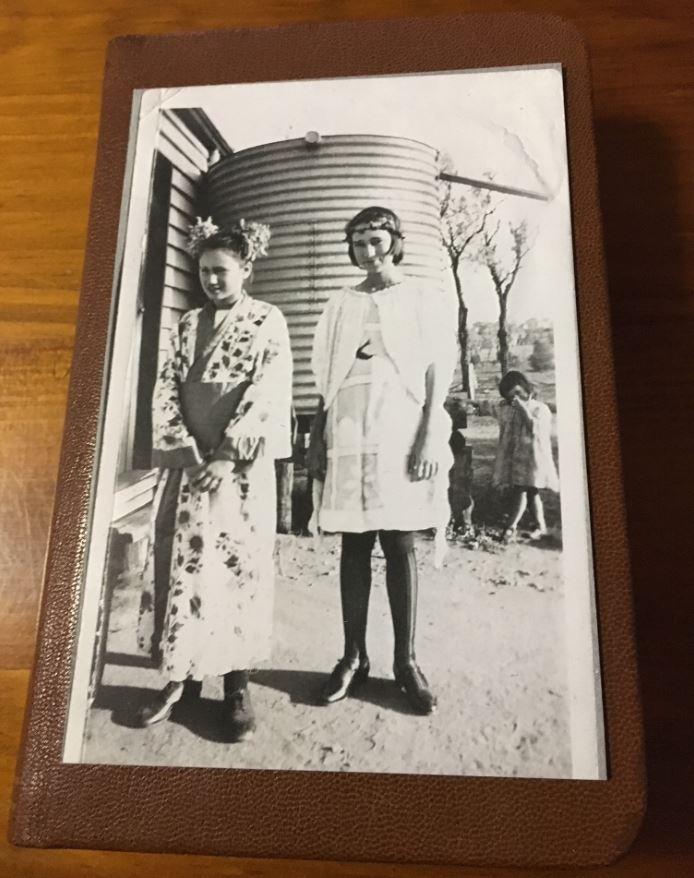

Victoria Margaret Watt, standing by the tank, in a photograph of two of her older sisters, Sis and Molly, in fancy dress. Photo: Courtesy Murray Watt

A few years later, she was lucky to survive once more.

“When I was about six, one of my sisters was home from boarding school, and I just absolutely loved her,” Mrs Watt said. “There was an annual rifle shoot on the range near my hometown, so my sister and her friend from boarding school went for a walk and, of course, I flashed by my sister and I decided to gather some wild flowers. Every two minutes the riflemen would fire off to try and hit the target, and I suddenly found that I was alone. I thought, where’s my sister? Then I saw her opposite me, right across the other side of the range, so what did I do? I ran across the firing range, and this rifleman, as he pulled the trigger, he saw this little girl in range…

“He thought he’d shot me, and of course he fainted, and he didn’t see this little girl still running across the range. They found out later that when he pulled the trigger, the bullet had jammed in the barrel.

“Of course, my oldest sister and her friend weren’t very popular with my parents after that … and children were not allowed at the rifle range again.

“But I’ve had so many close shaves … I must have a guardian angel I think … It was just a miracle.”

Victoria Margaret Sullivan in the field, aged 18. Photo: Courtesy Murray Watt

She remembers growing up during the Depression years, her mother helping the “poor swagmen” as they made their way along the stock route after the First World War.

“My mother would have four or five men begging for food early in the mornings,” she said. “The homestead was just three miles from the stock route and they knew that a very kind lady – my mother – lived there. She learned to make bread, and butter, and cream, and all those things, so my mother used to load these men up with nice food.”

Her father was Irish and had moved to Australia as a child with his family during the potato famine in Ireland, and he knew what it was to go hungry.

The fifth of their 10 children, Mrs Watt, also remembers going to school for the first time and being teased because of her name.

“These cheeky little boys used to say, ‘Oh, here comes New South Wales, oh no, it’s Queensland, and then they’d say, oh no it’s Victoria,” she said with a laugh. “Oh dear, oh dear, I wasn’t very happy at all. I used to go home and I would cry and say I don’t like my name. But my mother and father would say my name’s Victoria because it’s Latin for victory.”

Victoria Margaret Sullivan aged 20. Photo: Courtesy Murray Watt

Growing up, she always knew the significance of the day she was born and would pause to remember.

“There was a soldier’s body found near the Amby cemetery,” she said. “He was buried in the Amby cemetery and he was known as the Unknown Soldier. They never found out who he was and every Armistice Day, the CWA had the school teacher march all the children to the Unknown Soldier’s grave and we would hold a service there.”

They were taught at school that the First World War was the war to end all wars, but the world was soon at war again.

“They were grim days,” Mrs Watt said. “It was a very serious time.”

Her sister Eileen was a nurse and her brother-in-law, Jim Kirkbride, was a Rat of Tobruk who served with the 9th Division's 2/7 Field Company of engineers, laying land mines, and cutting gaps through enemy minefields.

“He used to crawl out at night from where they were holed up, and he used to disable the German and Italian war transport,” she said. “And then he’d crawl back again with the rats.”

Her half-cousin, Arthur Ward, was killed at Kokoda in 1942. He and his three siblings had been reared by Mrs Watts’ parents after their mother died in a house fire, and Mrs Watt saw him as a brother; but Arthur never made it home from the war.

“A sniper shot him at Kokoda,” Mrs Watt said. “There were Japanese everywhere and poor Arty, he lived for a week. He was almost shot in the heart.”

Victoria Margaret Sullivan and John Edgar Watt in 1938. Photo: Courtesy Murray Watt

They were difficult days, and Mrs Watt ran a first-aid post in her home town of Amby while her fiancé, John Edgar Watt, worked on the railways.

“I did not see my husband to be for two years before we married,” Mrs Watt said. “It was during the war, and he was sent to Wallangarra [on the Queensland – New South Wales border].”

The army had established a stores depot there, and men were needed to work on the railway.

“Those men used to see the sun rising twice because they would have to do a double shift,” she said. “They were short of men because of the war and the railway men weren’t allowed to join the forces because they were needed on the railways.

“He was a station master, but they sent him to Wallangarra as a shunter and he nearly lost his life. Somebody left a door open on a train, and as he was shunting the train, he got caught on the open door, and fortunately it threw him away from the rail lines. He had a crushed foot, but he still worked.”

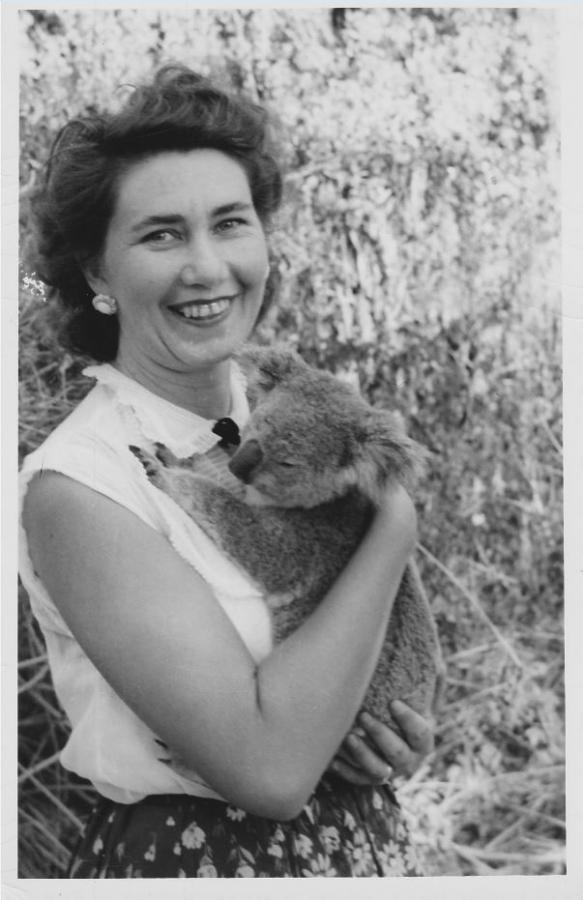

Victoria Margaret Watt, pictured with a koala, at age 40. Photo: Courtesy Murray Watt

He was eventually granted a fortnight’s leave to get married and they were wed at Toowoomba in June 1943.

“My husband had just a fortnight to find someone to marry us,” Mrs Watt said. “So when we arrived by train in Toowoomba, there was my future husband waiting for me. We hadn’t seen each other for two years, and all I could do was weep on his shoulder. It was wonderful. It really was.”

But the spectre of war was never far away.

“We didn’t know how long it would be before the Japanese were advancing on Australia,” she said. “They’d bombed Darwin, and one of my husband’s cousins, Ethel O’Keefe, was married to Owen Price, who was a squadron leader [in the air force]. They came to our wedding and he was on his final leave and they called for volunteers to bomb Rabaul Harbour.

“Owen Price had been on a reconnaissance flight [when] they found Rabaul Harbour was bristling with Japanese warships … so he volunteered to lead the squadron.

“They bombed Rabaul Harbour and blew the warships to pieces, but Owen and some of his squadron were bombed, and Owen’s plane was never found, so the plane and his body must be still down at the bottom of the sea.”

She remembers moving to a boarding house at Wallangarra with her new husband and fearing the worst.

“That was a fairly grim time of the war,” she said.

“There were Javanese prisoners of war there, and they were allowed to go to the pictures, but amongst the Javanese, there were two Japanese spies.

“The mountains around Wallangarra were bristling with Australian ammunition. It was buried there, and the spies knew about it, and they attempted to blow up where they thought the ammunition was. There were tonnes of it, and my husband and I were asleep in bed, and as I speak of it I can still remember the vibration before the explosions.

“There were two explosions, but they missed their target, thank goodness, because had they made a direct hit, that would have been it for Stanthorpe and Warwick and all those surrounding towns – we would have been blown to pieces, so that was close.

“That was a grisly kind of experience that, and I was rather pleased to get away from Wallangarra … but then peace came and our family came along, and I was blessed with three sons and a daughter.”

Victoria Margaret Watt with her family in 1950. Photo: Courtesy Murray Watt

Today, she has 11 grandchildren and 11 great-grandchildren and still considers herself blessed.

On Sunday she will mark Remembrance Day with two minutes’ silence as she has always done, before celebrating her 100th birthday at her home in Queensland with family and friends. She has made four dozen lamingtons and decorated four dozen little patty cakes for the festivities, but admits her “doctor doesn’t know about that”.

“Oh yes, my word,” she said. “I would not let the side down. We must remember and have two minutes silence on my birthday at 11 o’clock on the 11 of November 2018.

“My father used to say a minute’s silence for the war, for the soldiers, and a minute’s silence for my poor wife … He used to tease me, but it was always drummed into us that it’s a very special day, not because it’s my birthday, but because it’s Armistice Day.

“One hundred years is a long time and we must remember, but I didn’t think that I would still be around.

“And I’m so grateful … I was blessed that way.”