'It makes you feel proud, knowing he's part of our family'

Warning: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, please be advised the following article contains names and images of deceased people. It also contains examples of racist and offensive language that was used at the time.

William Yeo had to fight to serve during the First World War.

He would enlist three times in four years, and be discharged twice. The reason: he was Aboriginal.

Determined to do his bit, he went on to serve on the Western Front and was killed in France just months before the end of the war.

He was one of more than 800 Indigenous Australians who served during the First World War, despite restrictions in place preventing them from doing so.

More than 100 years after he died, members of William’s family met for the first time at a Last Post Ceremony commemorating his life at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra to mark Reconciliation Week.

Jane Chamberlain, right, at the Last Post Ceremony commemorating her great-great uncle, William Yeo.

Jane Chamberlain was one of the family members who laid a wreath in William’s honour, along with some gum leaves from his hometown.

“It's just such a gift that the War Memorial is giving us all as a family,” she said.

“And I'm so grateful for the people that have volunteered and put together the story of my uncle's service.

“It's 104 years, eight months and 30 days since our dear uncle died in battle, but all good things come in time...

“My dad, David Chamberlain, is a Vietnam veteran and he’s been researching our family history for 30 years, so this is enormous.

“My grandfather used to tell people that he was Maori ... and it makes me sad that society did not let my grandfather feel comfortable enough to acknowledge who and where he was from.

“This service is going to give [our uncle] dignity and it's going to give our family peace of mind... that he's being thought of in such a good and encouraging way.”

William Henry Yeo was her father’s great-uncle. He was born in Frogmore, a small village in the district of Burrowa, New South Wales, in about 1890.

When his father – also named William Henry Yeo – died in 1895, his mother, Harriet, was left to bring up the family alone. William was about 10 years old, when he and his two younger sisters were sent to the Benevolent Society in Sydney. Elizabeth, known as Maude, went to live with two spinsters in Wollongong, while Lucy was brought up in Sydney. They would never see each other again.

By the time war broke out, William was working as a labourer in Queensland. He enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force at Enoggera on 29 October 1914, shortly after the war broke out, listing his mother, Harriet, as his next of kin.

A week later though, William was discharged. A note on his service record read simply: “Discharged 7/11/14. Not likely to become an efficient soldier.”

Not to be deterred, William enlisted again, just six months later, on 28 May 1915. He was allotted to reinforcements for the 15th Battalion, but the commanding officer of the unit wrote to the camp adjutant on 23 June 1915: “This man is a half caste Aboriginal of a low order of intelligence. He is slow witted and stupid and is not likely to become an efficient soldier. He has on several occasions caused trouble in the lines and his presence is prejudicial to the good order and discipline of this unit.”

William was discharged for second time on 9 July 1915.

Eighteen months later, on 3 January 1917, William enlisted for the third and final time. This time he enlisted at the Sydney Showgrounds, making no mention of his previous attempts to enlist, and was successful. He embarked for overseas service three weeks later and went on to serve with the 54th Battalion on the Western Front in Belgium and France.

He was killed in action on 1 September 1918, during the fighting at Peronne.

Today, William’s remains lie buried in the Peronne Communal Cemetery Extension underneath the inscription chosen by his mother: “The Lord gave, the Lord hath taken away, for he was my darling boy.”

His name is listed on the Roll of Honour at the Australian War Memorial, alongside the names of almost 62,000 Australians who died while serving in the First World War.

His sisters’ descendants would go on to serve during the Second World War and in Vietnam.

Both sides of the family were told they were Maori, rather than Aboriginal.

They were reunited for the first time at a Last Post Ceremony commemorating William’s life.

Members of the Crimmins and Chamberlain families met for the first time at the ceremony. Pictured from left to right are: Robert Crimmins, Michael Crimmins, Jane Chamberlain, David Chamberlain, Margaret Green and Eric Chamberlain.

For Robert Crimmins and his brother Michael, it was particularly poignant. Their grandmother was William’s younger sister Maude.

“She was only very young, only about four or five years of age, and she had a pretty rough life,” Robert said. “She was brought up by two spinsters who lived in Crown Street, Wollongong. They had shop, a seamstress shop, and that’s where she lived. But she always called herself a Maori... It wasn’t until later in life that it came out that she was actually Aboriginal, and that’s when we started looking into it.”

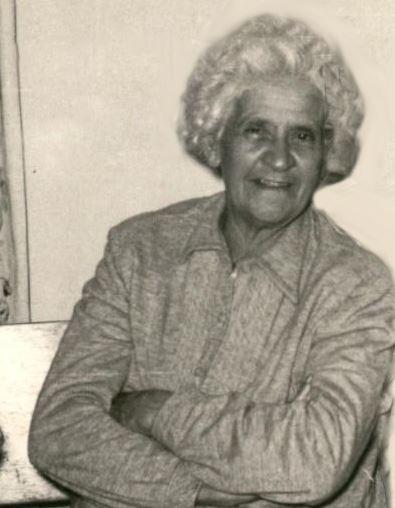

William's sister Elizabeth Maude Crimmins (nee Yeo). Photo: Courtesy the Crimmins family

They were researching their family history when they discovered William’s story.

Robert’s father, Reg “Tuppy” Crimmins, was captured by the Japanese during the Second World War.

“He was sent to work on the Burma railway and was actually hit by a carriage there,” Robert said. “I don’t know how he didn’t die, but he survived; and then he was sent to Japan to the Mitsubishi mines at Nagasaki...

“When they were shipped up to Japan from Thailand, they had to stand all the way, they were packed that tight in the hold, and then they were fed rotten eggs and rice...

“But Dad was one of the lucky ones, he got through...

“The first convoy that went through was sunk by the Yanks – they didn’t know they were prisoners – and the convoy behind him got sunk, and there were no survivors.

“Dad really suffered in the war ... and the stories he could tell were horrendous. But he didn’t say much... He actually saw the atom bomb go off, and three days later they trucked them in to Nagasaki to help clean up...”

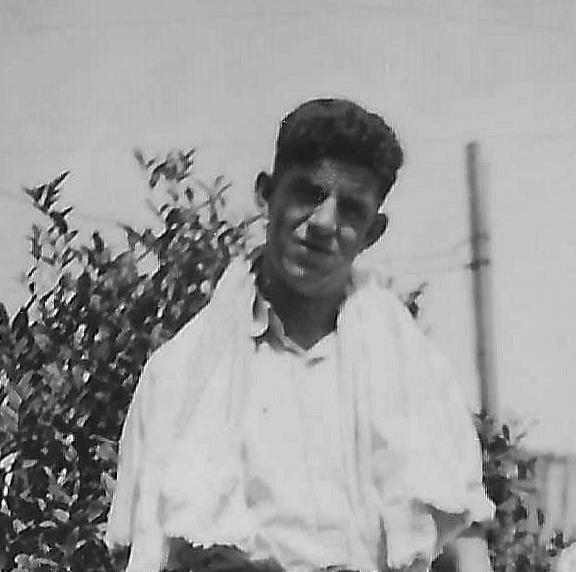

Reg "Tuppy" Crimmins. Photo: Courtesy the Crimmins family

His brother Jack “Sharky” Crimmins served in the Middle East.

“He was known as Sharky because he was such a great swimmer. They thought he was going to make the Olympics, he was that good, but the war came and he went over to the Middle East ... and he got mentioned in dispatches. But their younger brother, poor old Colin James, was only 18, and he got shot and killed in New Guinea.”

Robert has been working to get William’s name added to the war memorials at Reids Flat and Burrowa, where he was from.

“My mission in life is to get his name on that plaque,” he said. “The poor bugger died for us... and he gave the ultimate sacrifice ... but his name’s not there.

“He’s earned the right for his name to be there... so I’ll keep persisting.

“How many guys would have done what he did ... after the way he was treated ... God bless him.

“So I’m doing it for poor old Uncle William, but I’m doing it for Nan too. He was her brother and she would have wanted it done.”

Jack "Sharky" Crimmins. Photo: Courtesy the Crimmins family

Colin Crimmins was killed in New Guinea. Photo: Courtesy the Crimmins family

For Robert’s brother Michael, it’s been quite a journey of discovery.

“It really does put you on a journey, and it still is, very much,” Michael said.

“It was special to find out about grandma’s history and then we found out about Uncle William and his story and the barriers that were put up in front of him to go to war.

“There was never any real talk about the Aboriginal culture or our connections to it and I didn’t even know he existed... It makes you feel proud, knowing he's part of our family, but it gives you pride too, knowing what he’s had to overcome... the discrimination and the criticisms ... but he still returned....

"He could have quite easily said, ‘Bugger you, if you don’t want me here, I won’t come,’ but he kept on going and unfortunately he paid the supreme price.

“To me, he was a man of character, and he displayed that by pursuing his patriotism for a country that was actually telling him, ‘We don’t want you.’

Robert Crimmins, centre, lays a wreath at the Last Post Ceremony with his brother Michael and his sister Margaret.

“It shows what Indigenous people were up against in those days, the strength of the discrimination, and people's willingness to flout it too. It's something that makes you very proud and happy to be part of what William showed to be a proud and resilient culture...

“He was sick too, the poor man... and he didn’t do it easy at all ...

“A lesser man would have chucked the towel in I reckon and said, ‘Get me out of here,’ but he kept on going back...

“He sounds like he was a bit of a larrikin as well, and he had his moments, but he still stood up for the fight, and he didn’t back down...

“The world hasn’t had a great history of being understanding and inclusive as far as Indigenous peoples are concerned, and I don’t think anybody really has shown the respect and the gratitude that Indigenous people actually went to war for a country that was discriminating against them...

“It just reinforces the willingness of Indigenous people to go to war for their country.

“And it didn’t stop with William... It’s carried on through Dad and his brothers, and through Robert, who served in the navy and then the Army Reserve. I was supposed to go to the air force, but I went to the police instead, and I hope I did my bit there.

“Dad was a prisoner of the Japanese for four years, and he suffered a hell of a lot.

“It was pretty horrific but he was pretty stoic and he never complained ... I only ever heard him talk twice about it....

“Growing up, we knew what Dad had gone through, that our uncle had died, and that Jack had served, but we never knew about William. The fact of the matter is, you never put all that in the framework of them being Indigenous or having indigenous heritage. That just makes it mean that much more.”

Margaret Green at the Last Post Ceremony commemorating William's life. Members of the Chamberlain family travelled from as far away as Queensland and Victoria to be at the Ceremony.

Like the Crimmins brothers, Margaret Green (née Chamberlain) was brought up believing her family was Maori. Her grandmother was William’s sister Lucy.

Four of Lucy’s children – George "Sonno" Chamberlain, Marguerite “Bubbles” Chamberlain, Francis “Digger” Chamberlain, and Cyril Raymond Chamberlain – would also serve during the Second World War. Two of her grandchildren – Jane’s father David and her uncle Eric – would also go on to serve in Vietnam.

William's sister Lucy Chamberlain (nee Yeo). Photo: Courtesy the Chamberlain family

“Dad used to you say, 'Your grandmother said her grandmother was a Maori princess,'” Margaret said. “And when I was at school, Dad just said, ‘Tell them you're Maori.’

“I actually believed it for years and years and years, and it wasn't until just before Dad died that my brother found out we were Aboriginal.

“I thought, why didn’t Dad tell us? But now I understand ... because of the Stolen Generation. It happened to his mother and I think he was just trying to protect us, and I’m glad that he did because who knows what could have happened?”

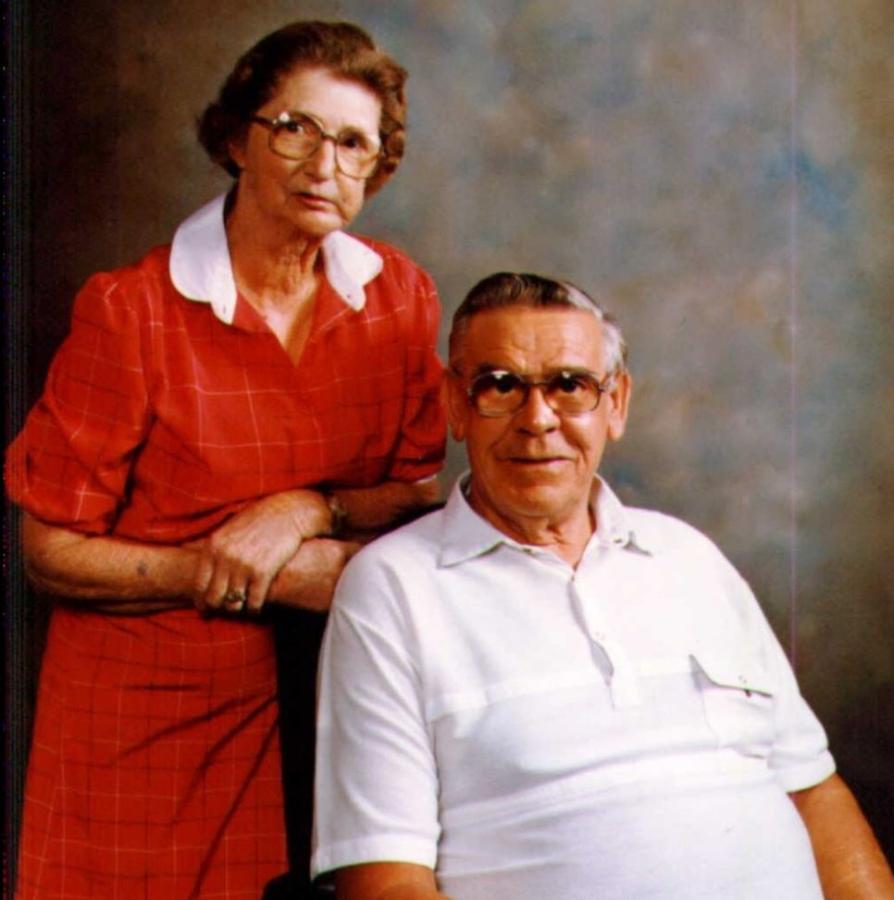

Margaret's father George Chamberlain, pictured in uniform, with her mother Joan Agnes Weeks on their wedding day on 20 November 1942. Photo: Courtesy the Chamberlain family

She was thrilled to learn her great-uncle’s story would be told at a Last Post Ceremony to mark Reconciliation Week.

“I haven't got words to describe it,” she said. “I just feel so proud, I really do.

“When my brother sent me the documents saying [our uncle William] was kicked out because he was half-witted and all that, I thought, ‘You're joking.’ It’s just horrible and I couldn't believe it...

“I'm so happy he’s finally been recognised... and that it's bringing the family together.

“It’s about time.”

George Chamberlain and his wife Joan. Photo: Courtesy the Chamberlain family

Margaret’s daughter, Amy Norman, agreed.

“It was a real eye opener, that's for sure,” she said.

“It's one of those things that many other families have gone through as well, but to read that he tried so hard to fight for our country so many times, and got knocked back... because of his colour is very, very sad.

“Knowing everything about him, and how he was treated ... but he persevered and he kept going... he never gave up and he died doing what he loved doing and fought for his country.

“To know that he's finally being recognised, and that he’s being recognised as an Indigenous warrior, is just amazing.

“It means a great deal, it really does.”

William Henry Yeo is one of more than 800 Indigenous soldiers who served during the First World War. The Memorial’s Indigenous Liaison Officer Michael Bell has been working to identify and research the extent of the contribution and service of people of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent who have served, who are currently serving, or who have any military experience and/or have contributed to the war effort. A proud Ngunnawal/Gomeroi man, he is interested in further details of the military history of all those people and their families. He can be contacted via Michael.Bell@awm.gov.au