'I knew in my heart that it had happened'

Sergeant William McDougall during the war. Photo: Courtesy Anne Coutts

Anne Coutts will always remember the last time she saw her father. “I was five,” she said. “I was sitting by my mother and my brother Jim was sitting on his knee sipping his tea, and that was the last time.”

Her father, Sergeant William McDougall, was killed when the hospital ship Centaur was torpedoed and sunk by a Japanese submarine off the coast of Queensland during the Second World War.

The white-hulled vessel was ablaze with lights, its red crosses clearly visible, when it was attacked just before dawn on 14 May 1943, while most people on board were asleep.

Anne’s father was on his way to New Guinea with the 2/12 Field Ambulance when the torpedo struck Centaur's port side, hitting the oil fuel tank and igniting a massive explosion. In just three minutes, Centaur was gone. Of the 332 people on board, only 64 survived. They were discovered 36 hours later.

Sergeant William McDougall was known to everyone as a kind and gentle man. Photo: Courtesy Anne Coutts

“It was a huge trauma, as you can imagine, to my mother, and to myself,” Anne said.

“I was told by the girl next door and I rushed to my mother and asked her. She said, ‘No,’ but I knew in my heart that it had happened.

“Many nights we sat together, while my mother was sewing, listening to the short-wave radio for any indication that he might have been picked up, or was in a prisoner of war camp, or something like that.

“My mother wrote hundreds of letters to the Red Cross to see if there had been any news and they were all sent back to her.

“In the end there was no hope. She got a telegram initially saying that he was missing, believed drowned, but then she got the final telegram saying that he had obviously gone down on the Centaur.”

Her father’s story was told at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra during a Last Post Ceremony marking the 76th anniversary of the sinking. “It was lovely,” Anne said of the ceremony. “He was a giving person … a kindly soul … and … it’s recognition of his service and of the man that he was.”

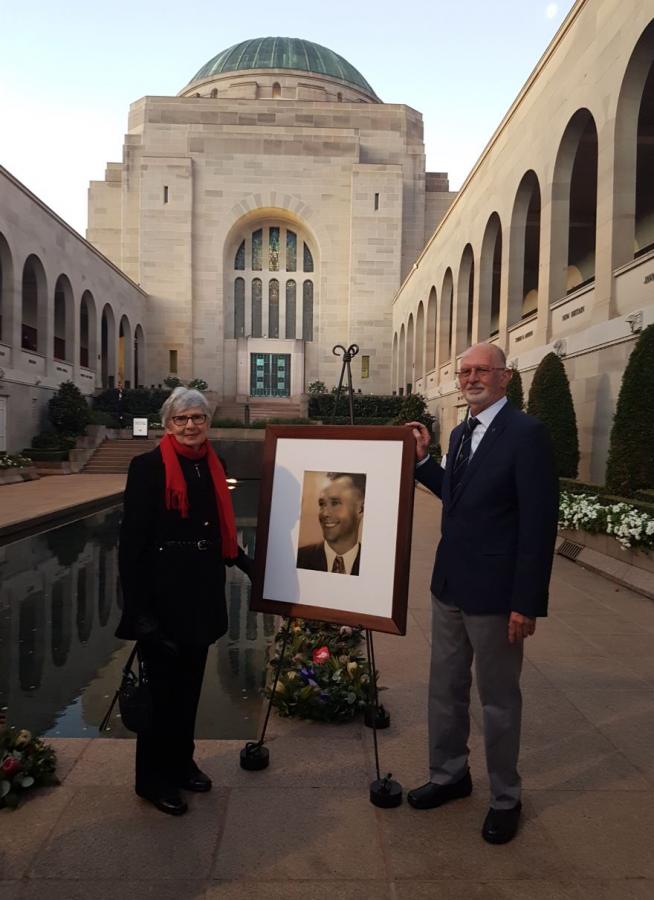

Anne Coutts and her brother Jim McDougall at the Last Post Ceremony at the Memorial.

William McDougall was born in the Sydney suburb of Redfern in 1911, and grew up during the Depression years in a small old weatherboard house in Drummoyne.

“He was always known to everyone as a very kind and gentle man,” Anne said. “He had to leave school early to help support a family of five children, and if he was not in work, he did things to help his mother. He extended the house, opened up windows and all that sort of thing, and at one stage, he had a horse and cart to sell fruit and vegetables, but he spent more money on the horse, and he couldn’t bring himself to give damaged items to customers.”

When an opportunity came up to work at Callan Park Mental Hospital, Bill, as he was known, sat the public service exam and began training as a hospital attendant. He was well suited to nursing and soon gained a reputation for being able to calm the most unsettled patients.

By the time he qualified, he and his wife “Nan” were saving to buy their own home. He often took their daughter Anne along with him and she would sit happily in his workman’s bucket, while Nan sewed baby’s clothes at home to sell to the shops.

“When war broke out … my parents … discussed whether he should enlist,” Anne said.

“He was a religious man in a non-denominational sense … [and] the outbreak of war deeply troubled him as he could not contemplate killing another man.

“He wrote some beautiful poems and prayers … [and] in his poetry expresses grief over man’s inhumanity to man … He decided to join in his capacity as a nurse, and in fact, it was only on the condition he served in his nursing capacity that he was released from the hospital.”

Anne's parents, William and 'Nan' McDougall, on their wedding day. Photo: Courtesy Anne Coutts

He enlisted in January 1941 and joined the 2/12 Field Ambulance, where he could use his nursing skills and would not have to bear arms.

In July that year, Anne’s brother Jim was born. As he grew, Nan would take him to the photo of Bill she kept on the mantelpiece, point and say “Daddy”. Soon he would smile and say “Dadden” back to her.

Meanwhile, Bill McDougall was sent to the Northern Territory where his unit provided medical support for the 23rd Brigade, participated in the construction of five small medical hospitals, and assisted sappers and pioneer assault units.

Bill had been trained as theatre nurse by the doctor in charge at Bagot Hospital and was on duty when the Japanese bombed Darwin on 19 February 1942.

“When they heard planes overhead they thought they were from our own air force,” Anne said.

“But when the bombing began they realised it was the Japanese and quickly secured the patients under their beds. They then looked outside and were able to see the faces of pilots as they flew overthe hospital. One fired his machine-gun. He did not hit the hospital, but bullets went through the walls of the hut where the staff ate and one ricocheted into a mug on one of the tables …

“He was assisting the chief doctor in the operating theatre and they were bringing in casualties in incredible number…

“[He] told [my mother] the floor of the theatre was slippery with blood, but they did not have time to mop up … They operated for 19 hours, on 92 patients, though he said the official raid count was 64.

“He was then supposed to go to Ambon, but the head doctor said he couldn’t part with him; he was too important.”

Anne Coutts and her brother, Jim McDougall, at the Last Post Ceremony for their father with family members and the Director of the Australian War Memorial, Dr Brendan Nelson.

Instead, he taught servicemen and servicewomen who did not have nursing training, and was thrilled when home leave came at last. He had been away for two years and was able to see his son Jim, now 18 months old, for the first time. As he worked around the yard at home, putting up side fences, making a swing, and laying paths, Jim followed his every move and imitated him; coughing when he coughed, and yawning when he yawned.

From her earliest days, Anne remembers a sense of wonder at the beauty of the flowers in the gardens of their street, the bread they bought still warm from the baker, the amazing smell in his shop, and then the marvel of the baker's horse eating his hay at the end of his round, all on the way to the newsagent where her father would buy a small book which they would then go home to read together.

She remembers tiptoeing into the bathroom when her father was shaving, being discovered and having her nose dabbed with shaving cream, amid roars of laughter. He had a keen sense of humour and there was lots of fun, but she also remembers being smacked when she did something wrong, and later sitting with him on the swing, both of them crying.

“Such memories bring tears each time they are recalled and the sense of loss does not lessen with the years,” she said. “His next time home was the last.”

Bill’s unit was at camp in Pymble when they were given three weeks’ leave. Nan wrote that she could not sleep that first night, frightened she would wake up and find he was not there.

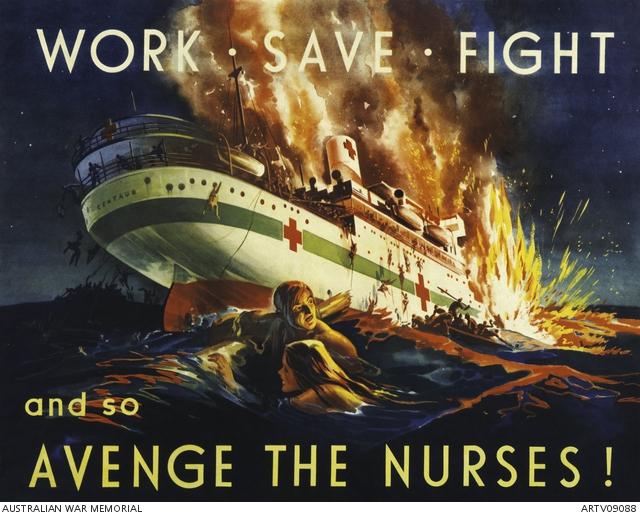

The hospital ship Centaur in Sydney in 1943.

When the unit moved near Wollongong, Bill arranged for his family to board with a generous widow who took them in, as well as another family from his unit. When they visited in the evenings, they would gather round the piano and sing hymns together.

“When [she] saw the men had changed from khaki to jungle greens she knew they would soon be moving … and all too soon the camp broke,” Anne said. “[My mother] later wrote that she could never hear The old rugged cross without breaking up.”

On their last family visit to his tent, Anne remembers her brother, Jim, sitting on their father’s knee drinking from his mug of tea; her mother later writing of the clinging embraces and sad waves goodbye.

That was on Monday 10 May 1943. They left the house they were staying in, caught a train to Sydney and then a taxi home, hoping that the men would get back there that night. They didn’t, and the next day they had word that they would not be home for a long time.

The following Monday, Nan left Jim with her neighbour and took Anne to start school. On her return she received a telegram saying Bill was missing, believed drowned.

“The horror, the shock of it, cannot be described,” Anne said. “My mother went to [his] parents’ home with the news. His mother… was totally overcome. One of his sisters went to the corner phone and rang Garden Island where their father worked to ask him to come home. They all sat by the radio to hear the lunchtime news – that the hospital ship Centaur, on an errand of mercy to evacuate sick and wounded from New Guinea, was steaming north from Sydney when it was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine and sank off Stradbroke Island at 4.10 am on 14 May. Some men had been picked up on Saturday at 4pm [and] the family realised that was where [my father] was missing.”

The loss of Centaur deeply shocked Australia, and for many Australians she became a symbol of the determination to win the war.

“My mother couldn’t accept the fact that he was dead,” Anne said. “She kept hoping that the sub would have picked up prisoners and she wrote off to the Red Cross just in case. She could not believe that God would create such a wonderful love and let this happen, so she prayed fervently. It took all her willpower to get up each morning to attend to [us].”

Anne remembers they lived on bread and milk for a week, with an occasional egg from a neighbour.

When another telegram arrived three months later announcing her father was missing, presumed dead, her mother wrote that it was the end of the world for her. Anne remembers hearing her mother calling out in the night: “God, God what have you done to me!” She would run to her mother, but was sent back to bed. Nan was inconsolable.

Legacy stepped in to help and eventually Nan came to terms with her husband’s death. She went on to run a clothing factory, remarried, saw Anne and Jim through their tertiary studies, and became a teacher and a devoted grandmother. She volunteered with children who had learning difficulties, and was posthumously awarded the OAM for her services. She died of lymphoma aged 86 in 2000.

Today, Anne and Jim remain enormously proud of their parents. “I treasured all that in my heart,” Anne said. “They shared an extraordinary love, had high ideals and lived by them … Even though she remarried, she always kept the love for my father there. When she was dying she asked if we would scatter her ashes over the site of the Centaur, I suppose, in a sense of being reunited with our father.”

Anne and her brother Jim hired a light plane to carry out their mother’s wish, but were devastated when they found out that the area that was thought to be the site at the time was wrong.

It was an upsetting end to an already tragic story. “We were terribly disappointed as you can imagine,” she said. “But then when [Centaur’s wreck was found in December 2009] we heard about David Mearns and his submersible going down and we saw the photographs, particularly of one of the hats and a boot, it just was a feeling of completion; that it was at rest … and at peace.”

The site is now a memorial to the lives that were lost.