With the Dayaks in Borneo

Air-dropped into enemy-held territory, a small Allied force prepared the way for the final assault. By Robyn van Dyk for Wartime Issue 81.

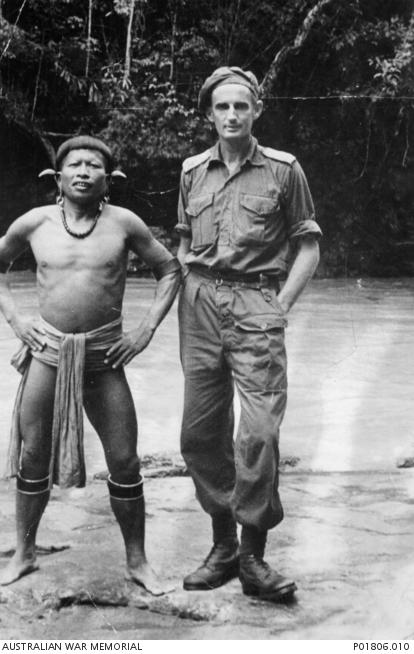

Dita Bala, Kelabit chief from Long Dati, and Major Gordon "Toby" Carter DSO, Z Special Unit, 1945.

The mission was classifed Top Secret: to penetrate deep behind enemy lines, gather intelligence on Japanese locations and movements, and to organise, train and arm local people into resistance groups to wage guerrilla warfare. At midnight on 25 March 1945, the first party of eight men of Z Special Unit under Major Tom Harrisson took off in two B24 Liberators, two carrying personnel and the third stores. Harrisson was a Briton serving with the British army’s Reconnaissance Corps, and he’d had some anthropological experience among the peoples of Borneo and the New Hebrides. The party was heading deep into Borneo’s uncharted jungle highlands. “The feelings of us left on the ground watching the first party leave,” wrote Major William Sochon, leader of a later party, “definitely left a lump in the throat, knowing that they were going into unknown danger and possibly it would be the last that we would see of them.”

The occupation of Borneo by the Japanese in December 1941 contributed to Australia’s growing unease that war was coming to its doorstep. Borneo was colonised by Europeans in the 19th century. The British Brooke family had carried the title of Rajah in Sarawak for three generations; but the last rajah ended his rule in exile in Melbourne. Lady Brooke, wife of Rajah Sir Charles Vyner Brooke, pointed out the only other thing that Australians might know about Borneo: “If the Japanese try to penetrate Sarawak, the head hunters, who have many devices to get a fine collection, will welcome them, and I wish to get a few Japanese heads myself.”

The Japanese occupation concentrated on Borneo’s coastal oil areas and cities, although its forces pressed inland, seeking local food supplies. By 1945 the Allied blockade of the area had proved successful in isolating the island and limiting access to the oil. The blockades also led to serious hardship for the people of Borneo. They lost access to their traditional trade markets, and goods such as food, cloth, medicine and salt were in short supply. The Japanese controlled trade and paid little for food from the local population, compounding the hardship. Local people, even remote groups, were broadly aware of the brutality of Japanese rule. Assisting downed airmen or prisoners of war, or engaging in any underground activity in Borneo, would be undertaken only at great personal risk. If a man was caught, torture and death were likely, and the terror was often extended to families.

The Australian-led liberation of Borneo began in June 1945 with the operations called Oboe and more than 75,000 Australians landing on the island. Oboe was the last large-scale Allied operation of the Second World War, and the largest amphibious operation in Australia’s history. The success of the Oboe operation required early reconnaissance, intelligence about the enemy, and a better understanding of the terrain and the indigenous people. Several covert operations were planned to put trained operatives behind the lines in operations code-named Semut, Agas and Platypus. They were under the command of Special Operations Australia, which used the code name Services Reconnaissance Department (SRD). The Army unit name was Z Special Unit, and it supplied the men serving on these operations. Major Harrisson, party leader for Operation Semut 1, wrote:

We were called SRD – here security was effective indeed, because no-one ever told us what it meant. It was mildly argued wherever we were, if we were Special Research Department, Special Reconnaissance Detachment or Services Reconnaissance Detail. Whatever the answer, it was the Z which buzzed for us. To be a Z Specialist was something to be proud about.

On 25 March 1945, the eight members of the Semut 1 reconnaissance party parachuted onto a high plateau that was home to the Kelabit people. The highest inhabited area was near the longhouse of Bario. The SRD party were there to investigate the safety and suitability of the area and to find other suitable drop zones.

Semut 1 personnel at Labuan, November 1945.

Photo: AWM2017-7-126.

Harrisson had made several reconnaissance flights in the months before the insertion, but little was known of the area: available maps were inaccurate and lacking in detail, and it was uncertain how the locals would receive them. The Australians also had no idea whether the Japanese were in the area. Jack Tredrea, a surviving veteran of Operation Semut 1, remembers being issued with a cyanide pill to swallow if he was captured. The party landed not far from the longhouse of Bario, but their stores were scattered over several kilometres. Soon villagers carrying a white flag came towards them; runners were sent to nearby villages, and by nightfall over 500 people had come in to help find the scattered stores.

Chiefs within three days’ walk assembled to discuss the question of supporting the Australians. The Kelabits had no direct experience of the war but had felt its effects, like most people on the island, because they were prevented from trading. They were experiencing great hardship from a lack of medicine and food, and they feared Japanese reprisals if they helped the Allied party. Harrisson wrote: “I rather think the people who dropped us in half-expected the headhunting hill tribes to chop our heads off as we touched down. But they didn’t. Within a few days it was obvious we could rely on one hundred percent support from them.” In a festive atmosphere a significant amount of borak, a local rice wine, was consumed, as Keith Barrie described/in his memoir:

A huge earthenware vat appeared in the communal part of the longhouse … and to the accompaniment of poetic rhetoric on the part of the headman, a scruffy half coconut shell was dipped into the liquid and proceeded to be passed round the assembled company from which each of us in turn took a good swig. … I really think that what gave added zest to ribaldry was an unspoken relief that we had found ourselves in such an unexpected relaxed and friendly atmosphere, instead of the expected traumas and tensions of having to deal immediately with hostile Japanese patrols.

The meeting was a great success, and the locals pledged support for the Australians. A headquarters in the mountains above Bario was established, including wireless transmission to Darwin.

Within days the reconnaissance party was told that some American airmen had crashed in the area and had been supported and hidden for many months. Fred Sanderson went to investigate and to provide medical aid for injuries, illness and malnutrition. Getting the men out would be difficult. Harrisson considered building an airstrip; he found a suitable site in the Bawang valley but the ground was too soft to land a plane. With huge local effort, a runway was constructed corduroy-style, using rows of split bamboo. Harrison was aboard the first plane to take off; it crashed, luckily with no injury, so the runway had to be extended. “The American airmen, the sick, prisoners, and many captured documents were flown out this way,” he wrote.

There were to be four Semut operations, which always included medical aid for the local people, thus gaining their support and intelligence. The next step was to arm and train the local volunteers, who were increasingly interested in taking up arms. Semut 1 alone, in April and May 1945, was able to supply some 300 rifles and instruction in their handling. By end of July, over 1,000 men were under arms, and some local forces were equipped with captured Japanese weapons. These were provided as a loan, and those who received them were made aware that the weapons would be recalled at the end of the war. Each weapon was issued to a particular person, and its serial number was recorded. The indigenous fighters also used their own weapons, including the parang, a traditional machete, and blowpipes firing poisoned darts. Tom Harrisson wrote, “The supreme advantage of the blowpipe is silence … If you miss the first time, no one hears or sees anything. You simply carry on shooting until you register.”

I rather think the people who dropped us in half-expected the headhunting hill tribes to chop our heads off as we touched down. But they didn't.

At several major events during the Semut operations, tribes that had been traditional enemies came together to lend their support. The coming together of the tribes at Long Akah in Sarawaj was photographed by Major Toby Carter. The Kenyah chiefs were shown arriving down the Akah River – some prahus (outrigger boats) flying the Sarawak flag, and one with the Union Jack. Photographs show the chiefs ascending to the British fort above Long Akah and gathering in welcome. At this meeting, Z Special Unit pledged support in the form of weaponry, and fighters from the Kenyah tribes pledged to support the Allies in fighting the Japanese. Following custom, a pig was killed and its liver examined to see whether or not the Allies were in the ascendancy. “The liver was read by the old man of the house and so found to be quite in order … he showed the necessary marks on the liver which proved beyond doubt … that the Japanese were to be defeated,” wrote Major Sochon.

The Services Reconnaissance Department encouraged the taking of Japanese heads. Headhunting was an indigenous custom, but had been outlawed for many decades under British colonial rule. Operation Semut 1 paid as much as five Dutch guilders bounty per head. Major Sochon wrote that when he met local chiefs, there was the usual question about whether they would be allowed to take heads. Sochon records that he explained to them “that this was a period of war and that as enemies of the country, Japanese heads could be taken.” In many areas, headhunting was crucial to keeping the support of the local people and thus to the success of entire operations.

Headhunting was not an expression of disrespect for the enemy, but rather the opposite: it involved bringing the enemy’s head (and hence his spirit) home and incorporating them into one’s own household. In some of the island’s cultures, it was a tradition for young men to take a head before marriage. Deep attachment to the practice meant that a licence to headhunt against the Japanese became an effective tool for recruiting young indigenous men to the Allied cause. Sochon wrote of a ritual involving a Japanese head:

The old lady of the house brought out a Dayak blanket (these are handwoven by the Dayaks and made from Kapok in various colours) and placed the Jap head on this. She would then be followed by all the virgins in the house, holding the blanket and the head as if it was a baby, in front of her, chanting … The following morning a small shed made out of jungle leaves was built and the head [was] roasted.

Sochon described a ritual that lasted for four days, and also involved feeding small delicacies into the mouth of the severed head.

On the 1 August the Semut operations turned offensive – closing off the Japanese retreat inland following the major coastal landings of Operation Oboe. On 15 August, after the Japanese government had surrendered, the SRD operatives were ordered to cease aggressive action. However, the Japanese, isolated in many instances, continued to fight, as well as stealing food, looting and killing in villages that the operatives had pledged to support. The war in Borneo ended with the official surrender of the Japanese 37th Army by Lieutenant General Baba Masao on Labuan on 10 September 1945. But there were many incidents in which Japanese troops ignored the surrender or refused to believe it. It was a difficult situation for the SRD operatives who had pledged to support the locals of the interior and now had official orders to cease hostilities. However, by the end of October civil order was generally restored and and a temporary administration installed. The Semut operations in Borneo had been a success in preparing for Oboe, but that had only been made possible with the support of the local indigenous peoples.

This article was originally published in Wartime Issue 81. Purchase your copy from our online shop.