'The Woman Who Threw Japs'

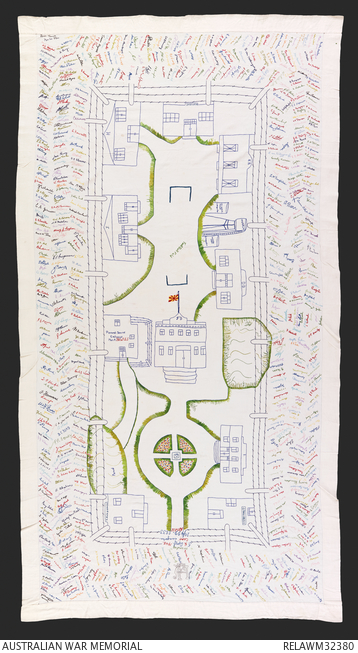

The embroidered Lunghwa tablecloth which depicts a map of the internment camp, surrounded by approximately 800 signatures.

A collector of historic Russian textiles, Alexandra decided to embroider a large antique tablecloth with a map representing the Lunghwa internment camp. Ten buildings are outlined and labelled from A to H, in addition to the water tanks, football field and a large pond. The central building was used as the administrative headquarters by the Japanese guards, and this is indicated by the Japanese flag flying above it. Stem-stitched grass is meticulously sewn in various shades of green silk threads, and four flower beds around a fountain reveal tiny, multi-coloured, chain-stitched flowers. The silk threads remain extremely vibrant, and Alexandra’s skills as an embroiderer are on full-display on this large and impressive tablecloth. However, for an unknown reason, she embroidered the Japanese Rising Sun flag in bright yellow and red instead of the traditional white and red. This curious creative decision has resulted in a Macedonian flag flying high in the centre of a map of a Japanese internment camp.

While Alexandra’s embroidered map is certainly interesting, it is made even more valuable to modern historians by the addition of approximately 800 embroidered signatures around the edges. The Lunghwa internees completed their signatures in pencil, before Alexandra over-embroidered the marks with colourful silk threads. Not only does this increase the visual appeal of the signatures, but it ensures that they are permanently marked upon the tablecloth. The Australian War Memorial acquired the Lunghwa internment camp’s nominal roll when a British woman, Peggie Orchin, recovered it from the Camp Commandant’s office after he had fled at the end of the war, and her son later donated it to the national collection. For my internship project, I am deciphering as many signatures as possible, and matching the signatures to names on the internment camp’s nominal roll. Once as many names as possible have been deciphered on the tablecloth, the online record will be updated with the full list to allow descendants to discover the connection between their relatives and this beautiful artefact.

Not only have a significant number of the signatures been deciphered and matched to the nominal roll (449 names, and counting!), but fascinating stories have been discovered about Lunghwa’s civilian internees. One of the most interesting internees is John Condor, a British civilian who worked for the Shanghai Municipal Police. He was having marital difficulties before the war, and being interned with his wife caused their relationship to further deteriorate. John requested to be transferred to a different internment camp, but the Japanese refused. Deciding that risking death was a better option than remaining with his wife, John scrambled under the barbed wire fence and escaped from the camp. He hid out with a group of Chinese nationalist guerrillas for a few months, before joining the British Army Aid Group (BAAG) and helping Allied POWs to escape from Japanese camps. Fortunately, John signed Alexandra’s tablecloth before his great escape, and his experience of internment will be forever connected with this artefact.

While John Condor’s story is probably the most daring, he was not alone in having an exceptional wartime story. Following liberation, British internee Marjorie ‘Peggy’ Pemberton-Carter met and married an exiled Georgian prince in New York. As Princess Peggy Abkhazi, she developed an extensive garden on Vancouver Island, Canada, which has now become a major tourist destination. Another remarkable story belongs to Ruth Clarke (née Johnson) who was a collector of Chinese art, particularly jade carvings. Ruth managed to smuggle two small jade carvings into Lunghwa by strategically placing them between two pieces of bread, and telling the Japanese that it was a sandwich. She kept the jade carvings secret throughout internment, and after the war she sold one to pay for her and her husband’s voyage to America. One of the most fondly remembered internees was Oliver ‘Nutty’ Hall, a British wharfinger, who was interned with his teenage children. Robert Bloomfield, a fellow internee, recalled how ‘Nutty was an absolute clown, loved by all. He sewed a thousand buttons on a black suit and performed on stage as a Pearly King in a music hall act. He was our version of Stanley Holloway’.

Although the vast majority of the internees in Lunghwa were British, over 30 Australian civilians were also interned there. Fred Drakeford, the brother of Australia’s wartime Minister for Air Arthur Drakeford, was one of the more fortunate internees. Upon his release from Lunghwa, Fred received a 41-line telegram from his brother. In addition, Fred was flown out of Shanghai on a Catalina flying boat which had been chartered by his brother, while less well-connected internees had to wait for a berth on a ship. William ‘Billy’ Tingle, a 4’11’’ Australian featherweight boxer and PE teacher, was also interned in Lunghwa. Following liberation, Billy moved to Hong Kong where he continued his advocacy for children’s fitness and exercise. In 1986, Billy was awarded an MBE for services to the youth of Hong Kong.

The civilians who were held at Lunghwa internment camp had extraordinary experiences, and the Alexandra Fowles’ embroidered tablecloth provides a key to their stories. This tablecloth is an interesting and beautiful record of the experiences of 800 civilian internees, which continues to inform modern scholarship of civilian internment during the Second World War.

Lucy Robertson is currently interning with the Military Heraldry and Technology Section, and completing a Master of Liberal Arts (Museums and Collections) at the Australian National University.

For further information about Lunghwa internment camp, please see:

Christina Twomey, Australia’s Forgotten Prisoners: Civilians Interned by the Japanese in World War Two (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

Bernice Archer, The Internment of Western Civilians Under the Japanese 1941-1945 (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2008).

James Michael Orchin, Destination Lunghwa: My Youth in the Largest Japanese Civilian Internment Camp 1942-1945 (Raleigh: Lulu Publishing, 2012).

‘‘Ruth Johnson Clarke ’12 and Margaret Johnson Corbett ’12,’’ Amy Ensley, Women’s History at Wilson College, last modified 1 September 2012, http://womenshistory.wilson.edu/2012/08/ruth-johnson-clarke-12-and-margaret.html.