Stitches and signatures

Wartime textiles weave many different stories in their efforts to support, honour and remember Australians at war. The Memorial’s heraldry collection contains many examples of fabrics that have been autographed with people’s names as fundraising devices, records or symbols of friendship. Collecting signatures in autograph and scrap books has long been a popular practice in many different countries and time periods and these autographs on fabric exist in a similar fashion. The following examples reveal just a few of their stories.

During the First and Second World Wars signature quilts were used as fundraising devices in Australia and elsewhere, such as in New Zealand, the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom. Although called a signature quilt, this term denotes the traditional definition of a quilt that is made from layers of fabric joined together to form a bed covering. In reality, they were normally tablecloths or sheets embroidered with names.

The idea was that a person could write their name on the fabric to be embroidered over by a number of skilled sewers in return for a donation to a particular war fund. The public was informed of the quilts through newspaper articles detailing the cost of the signature, which ranged from sixpence to five shillings, and the nominated fund. Successful appeals raised between £10 and £27, or between around $940 and $2,539 in today’s currency. This money enriched local Red Cross funds, soldier’s funds supporting military hospitals, convalescent homes, Prisoners of War and provided comforts for men on the front line.

Most signature quilts were embroidered with both names and decorative devices, including the name of the town or community where it had been made. The majority were embroidered in red on a white ground. Interestingly, the Memorial’s only First World War fundraising autograph quilt – the Rylstone quilt - differs as the signatures have been stitched on to the white linen ground with white cotton thread. Unfortunately this means that the quilt is very difficult to photograph in its entirety.

Detailed image of the Rylstone quilt.

Photo: REL28488.

Another detailed image of the Rylstone quilt. The difficulty of lighting the quilt for photography accounts for its yellowed appearance.

Photo: REL28488.

Although it is embroidered with the words ‘RYLESTONE QUILT’, it is actually a commercially produced sheet for a single bed that has been autographed and embroidered to make a quilt or coverlet. Over 900 names were written in pencil and then over-embroidered in white cotton using stemstitch. These included those contributing a donation, Australian Anzac ‘heroes’ and the names of soldiers who had enlisted from the Rylstone district. Identification of servicemen so far has showed that some were killed on Gallipoli and that all had enlisted between August 1914 and July 1915, implying that the quilt was completed by mid-1915.

The Memorial holds other signature cloths, notably from the Second World War period. Of note are the number made by civilian internees. These appear to be souvenirs and records of camp life, friends and events. Helpfully, they provide nominal rolls for curators and researchers. In addition, their creation alleviated boredom and boosted morale.

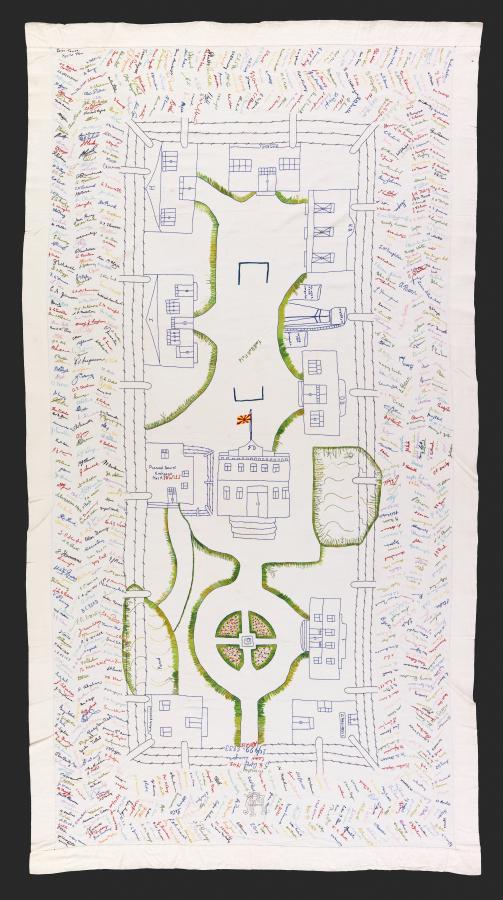

Embroidered autographed tablecloth of Mrs Alexandra Fowles, Lunghwa Civil Assembly Centre, Shanghai.

Photo: RELAWM32380.

My favourite example is the white linen tablecloth embroidered by Miss Alexandra Barr (later Fowles) during her internment at Lunghwa Civil Assembly Centre in Shanghai, China. The tablecloth was one of a number of personal items Mrs Fowles took with her into the camp when she was interned by the Japanese in April 1942. It was with the permission of her camp guards that she embroidered this record of her experiences. Mrs Fowles worked on the tablecloth during her captivity and continued into post-liberation. It was likely completed in 1947, after her marriage to Raymond Fowles in that year.

This cloth is actually a highly colourful map of the camp. Using stem-stitch, Mrs Fowles embroidered a rectangular fence forming the perimeter around ten buildings, three water tanks, a Japanese Imperial flag, two soccer goals and a football field. Also marked are a pond, four flower beds around a fountain, and the entrance gate. Around the edge of the cloth are nearly 2000 signatures belonging to the internees. Originally written in pencil, they were then over-embroidered by Mrs Fowles. Only two remain recorded in pencil.

Not only does this tablecloth shed light on the layout of the camp but it paints a picture of the social circles within it. The signatures are arranged in three columns around the edges of the tablecloth and form a number of groups. For families that were interned together, their signatures tended to appear in family groups. Similarly revealing are the number of demographic groups represented. For example, young American seamen, elderly missionaries and young mothers often signed their signatures in a specific location on the tablecloth. Names can be correlated with nominal rolls and show that of the identified internees, 66% were women. Of the women who signed the tablecloth, 79% were listed as colonial housewives. When women were listed as having an occupation, common responses were secretary, nurse and missionary. On the other hand, the occupations of the male internees were much broader and included business, government, shipping and missionary. A number of children’s names can also be found on the table cloth. These may have been signed by adults on their behalf.

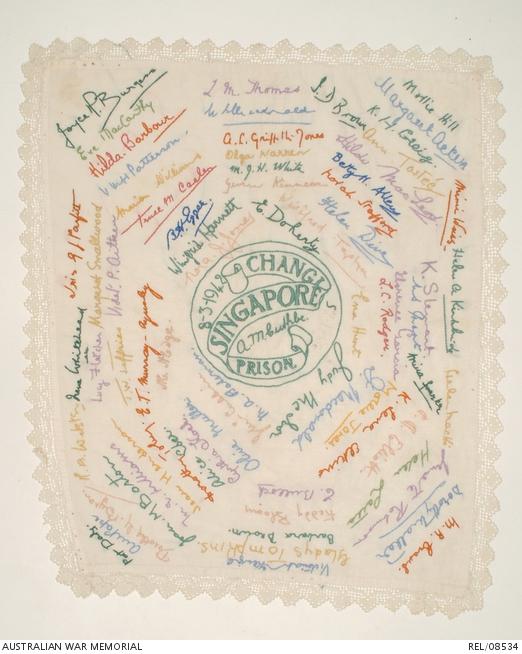

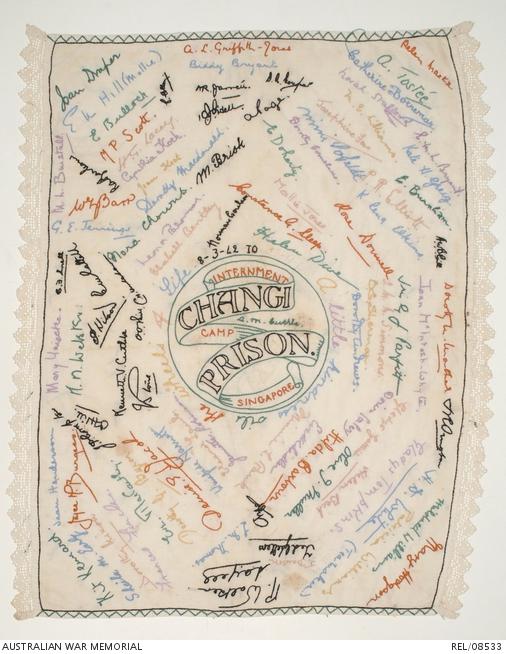

Embroidered souvenir signature cloth made by Mrs Augusta Cuthbe in Changi Prison.

Embroidered souvenir signature cloth of Mrs Augusta Cuthbe in Changi Prison.

Collecting signatures was also a means of retaining friendship bonds forged during internment. Two examples of this are the cloths embroidered by Mrs Augusta Cuthbe, a British civilian internee of the Japanese in Changi Prison and later at Syme Road, Singapore. Mrs Cuthbe used chainstitch and satinstitch in her first cloth to honour the female internees with whom she played Bridge. Chainstitch alone is used on the second cloth, used to record those who had shown her any act of kindness. Interestingly, although Mrs Cuthbe stitched in the date of her internment, she failed to complete the cloths with the date of her release. This strongly suggests that both were completed before that date.

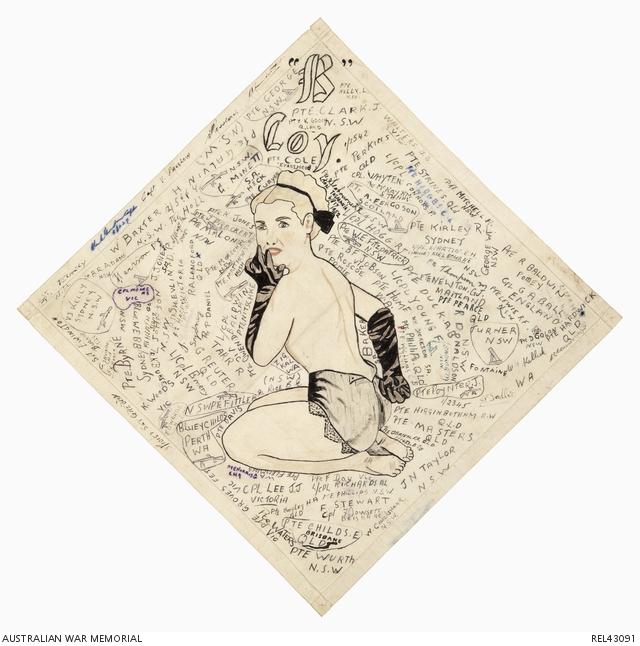

Decorated and autographed handkerchief of Private H W Curyer, 2 Battalion Royal Australian Regiment.

Though these examples may suggest otherwise, signature cloths were not a gendered activity and men too were interested in keeping material mementos of their service. Such cloths were also not always embroidered, as shhown by the risqué handkerchief decorated by 41336 Private Howard William 'Heck' Curyer, of B Company, 2 Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (2 RAR). After joining the Regular Army on 25 March 1952, Curyer completed his training at Puckapunyal in Victoria. The names recorded around the sultry central figure mostly belong to men who served in Korea, however not all can be identified as such. Curyer is therefore thought to have completed the drawing during his training after he was assigned to 2 RAR , but before the battalion left for Korea. The addition of the names may have been an ongoing process that was completed there.

These five textiles are but a sample of the material in the National Collection illustrating the practice of wartime autograph collecting. Signature cloths served a variety of purposes from fundraising, to records of internment and symbols of friendship. For further insight into the Memorial’s fascinating collection of autographed items, particularly the Private Records collection of decorated autograph books, please access the Memorial’s collection search.