Out in the Cold: Australia's involvement in the Korean War - War at sea: the Royal Australian Navy in Korea

- Home

- Timeline

- Origins

- Australians in Korea

- Australian Operations

- Weapons of War

- Faces of War

- Armistice and Aftermath

- Glossary

- Australians in Service

- War on land: The Australian Army in Korea

- War at sea: The Royal Australian Navy in Korea

- War in the air: The Royal Australian Air Force in Korea

- Medical Personnel

Australian ships in the Korean War

- Destroyers: Bataan, Warramunga, Tobruk and Anzac

- Frigates: Shoalhaven, Murchison, Condamine and Culgoa

- Aircraft carrier: Sydney

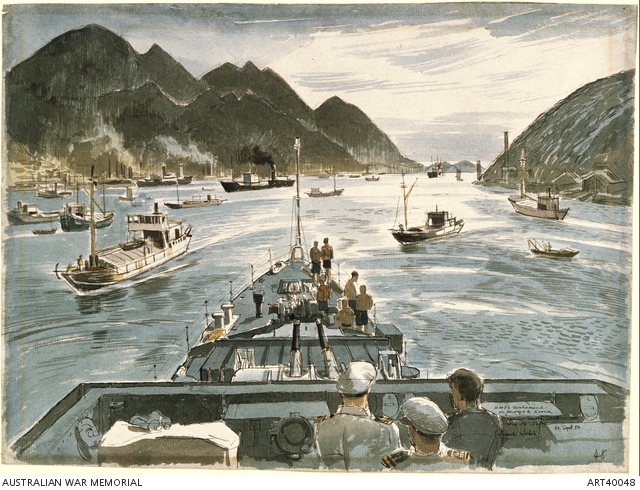

Korea is surrounded by water on three sides. Sea power was crucial to the UN forces in the Korean War, as UN ground forces were outnumbered by the Chinese and North Koreans. Control of Korean waters enabled the UN forces to launch the Inchon landing, which altered the course of the war.

The UN forces soon took advantage of their superior naval forces and seized control of Korea's long coastlines, using many ships to transport large numbers of troops and supplies throughout the war. The use of aircraft carriers, including HMAS Sydney, increased the numbers of aircraft available to the UN forces, enabling complete air coverage of the Korean peninsula.

On 1 July 1950, Australian frigates HMAS Shoalhaven and the destroyer HMAS Bataan joined a fleet enforcing the UN blockade. A month later, Bataan saw its first action when shots were exchanged with a North Korean shore battery. Other RAN ships were deployed shortly thereafter, bombarding shore installations and supply lines.

After mid-1951 and the beginning of negotiations between the two sides, naval pressure was increased against Communist ground forces by bombardments and blockades. HMAS Murchison played an important role in a naval blockade of the Han River from July to September 1951, Operation Han. For the last two years of the war, RAN ships in Korean waters continued to protect the islands off the west coast of North Korea that were in South Korean possession.

RAN armourers crowd together in the mess of the aircraft carrier HMAS Sydney, 1951.

Able Seaman A. "Happy" Anderson, using the gyro sight, lays a single Bofors gun, HMAS Bataan, August 1952.

“Generally speaking, the war in Korea demanded more competence, courage, and skill from the naval aviator than did World War II. The flying hours were longer, the days on the firing line more, the anti-aircraft hazards greater, the weather worse. There was less tangible evidence of results for a pilot to see.”

Commander M. U. Beebe, USS Essex

Naval airpower

Air squadrons flying from HMAS Sydney

- 805 Squadron

- 808 Squadron

- 817 Squadron

UN naval forces also served a vital function in providing added support to ground forces through the use of naval airpower. HMAS Sydney, an Australian light aircraft carrier, joined the war at sea in late 1951.

Sea Fury and Firefly aircraft of the recently formed Australian Fleet Air Arm, flown off Sydney, supported hard-pressed ground forces with rockets, bombs and cannon fire. They also flew combat air patrols to protect Sydney from enemy air attack.

“The Korean tour of duty had been costly, with eighty aircraft hit by flak and ten lost. Sadly, three Sea Fury pilots lost their lives and one was wounded … There were no casualties aboard, although there could have been when returning aircraft landed, sometimes still carrying 60-pound rocket projectiles that had failed to fire. As the aircraft hit the flight deck … the rockets launched themselves, speeding along the deck and then disappearing over the bow into the sea.”

Alan Zammit, civilian contractor, HMAS Sydney

Living Conditions

Australian Naval personnel in Korea endured severe hardships. Not only were the waters mined, but operations had to continue in appalling weather.

“At night lying in the hammock, listening to the floes scraping along the side for all the world like a great tin opener, made one thankful to the naval architect who had specified 3/8" plating for the construction. No doubt, the occupants of the lower seamen's and stokers' mess had very similar thoughts.”

Lieutenant Vince Fazio, HMAS Condamine

In winter, snow and ice covered the ships' decks, and sailors lived in cramped and often freezing quarters. Large naval guns were operated every ten minutes to ensure they did not freeze up.

In summer and autumn, typhoons brought rough seas and winds of up to 160 kilometres per hour.

Majestic-class light fleet aircraft carrier HMAS Sydney. From September 1951 to January 1952, Sydney served with the United Nations Command in Korean waters, where her aircraft carried out 2,366 sorties. 044798

Snow and ice cover the flight deck of HMAS Sydney. The cold weather has frozen some moving parts of the aircraft, preventing them from flying.

Ice covers the rails and cable equipment on the forecastle of the destroyer HMAS Bataan, North Korean waters, 1952.

Typhoon Ruth 14-15 October 1951

“All the mess decks were flooded. We had 8 inches of water sloshing to and fro on our deck, suitcases, hats, socks, boots all floating around together. … The ship was rolling and pitching all over the shop. … One plane went over the side and three others were hanging in the gun sponsons; two motorboats, the "skimmer", one forklift and a "Clarket" [tractor] all went over the side. Two chaps had legs broken through getting hurled to the deck. It sure was a boomer.”

Petty Officer Andrew Nation, HMAS Sydney

Typhoon Ruth hit the Japanese port of Sasebo, with winds up to 150 km/hour and waves estimated to be up to 13.5 metres. Warships and transport vessels, including HMAS Sydney, were stationed in the port at the time. Upon learning of the approaching storm, many ships had put out to sea to escape the now dangerous confines of the harbour.

Not only was HMAS Sydney in danger, there were many aircraft on board that were simply lashed to the ship because they could not fit in the hangar. The resulting damage from Typhoon Ruth was extensive. Many of Sydney's small boats were damaged, fires broke out from damaged electrical equipment, fuel leaked from aircraft, and general damage was caused on the decks by the violent waves around them. Sydney lost four of its aircraft overboard.

While some ships in the harbour were sunk, many Japanese were killed in Sasebo or lost their homes. The crew of Sydney, though having a long and hard struggle for almost two days, had been relatively lucky. Careful precautions and well-trained personnel had kept serious risks to the ship and crew to a minimum.