Shaping Memory: Sculpture at the Australian War Memorial

Special Exhibition

13 August 2004 to 28 November 2004

- Shaping memory

- First World War

- Second World War

- Post-war responses

- Memorials

- Future directions

- Medallions

Shaping Memory

There is an ancient link between sculpture and commemoration: the need to find tangible forms by which to mark the event of war. Sculpture has always played a central role at the Memorial: examples are displayed throughout the galleries and in the dioramas, and they also adorn the outside of the building and the grounds. In particular, sculpture has been used to capture the physical form, and thus convey essential human traits.

Since the First World War, some of the most proficient Australian sculptors, some internationally recognised and others not widely known, have worked to distil their attitudes and responses to war in the universal language of sculpture. The Memorial has continued since that time to commission and acquire sculpture, which, made in very different ways for a variety of purposes, encompasses the spectrum from major permanent outdoor monuments to more ephemeral, personal tributes and keepsakes.

Genesis of the collection

This exhibition charts the development and variety of styles of commemorative sculpture over the last century. It showcases the Memorial’s collection and includes a survey of official sculpture commissioned in response to the First and Second World Wars, through to works produced independently by artists over the last 30 years.

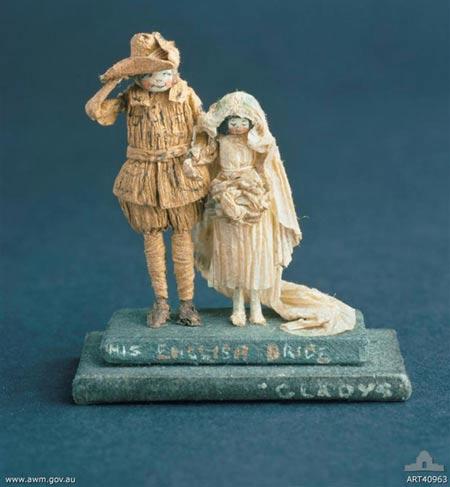

Many of these works challenge the preconception that commemorative sculpture is limited to the traditional, heroic bronze monument. The Memorial holds many pieces that explore other human qualities and responses to war. Privately-produced works such as those by Gladys Blaiberg show the experience of wartime from the civilian point of view, and contemporary works such as Ian Howard’s recent Signs of life pose questions about how we view the complexities of war. Seen together, they evoke a period of great change, both in artistic terms and for society as a whole.

Web Gilbert was largely self-taught as a sculptor. He established his own teaching studio and foundry in Melbourne before moving to London in 1914, aged 47. After working in a munitions factory, he reluctantly joined the Australian War Records Section in 1918. Appointed head sculptor for the proposed diorama scheme, he spent 13 months touring battlefields where Australians had fought.

From 1920 to 1925 he worked on the Second Division AIF memorial at Mont St Quentin, and took on other commissions, notably the Light Horse memorial at Port Said, Egypt, which was finished after his death in 1925 by Paul Montford and Bertram McKennal, and re-created by Ray Ewers after it was damaged in the Suez uprising in 1956.

Gladys Blaiberg 'His English bride'

Lyndon Dadswell

Bomb thrower

He laid in his composition in large eggs of clay and developed it with progressively smaller pellets, rolled around and applied with the forefinger, down to tiny little seeds of clay like tapioca The hollows were filled in to shallow undulations so as not to break up the sculptural mass. This method produced very sweetly modulated surfaces and exquisitely realized silhouettes. The piece would be rotated degree by degree, clay pellets being pressed on at arm’s length, one eye closed so that skyline flowed into skyline. It was an inhibiting process lacking directness and expression, but done properly it was elegant and beautiful and suited an art-deco style.John Dowie

Lyndon Dadswell

Stretcher-bearers

Dadswell’s work has been likened to Henry Moore’s: both artists were contemporaries whose work was moulded by similar ideas of simplifying form, and both were concerned with expressing the truths that lie behind the world of appearance. Dadswell also believed that commemorative sculpture should be designed for beautifying, rather than merely illustrating past deeds.

ART40930

Murray Kirkland

Portrait of Private Reginald Scanes

Private Reginald Scanes, the artist’s great-great-uncle, was gassed and died in France in 1918, aged 23. The artist has presented etched metal printing plates as finished works of art. They borrow from the style of low-relief commemorative plaques. By curtailing the printing process, Kirkland echoes the act of delving back through history, in order to find something more solid, in response to the feelings of grief generated for a man he knew only through the fragmented perspective of diaries.

For those of us generations removed from the Great War our view is a distant one. The scale of the horror and destruction and the tragedy it generated is overwhelming and incomprehensible one is inevitably confronted by statistics. At some point it becomes obvious that behind each number is an individual, a life.

Doug Sheerer

Game-play – January 17 – 2.44 am – 1991: (I)mplements of destruction, (S)tealth, (Y)eah, (N)ose Up, (G)round briefing, (I)n flight, (F)ix target engagement

A contemporary artist based in Perth, Doug Sheerer works with the artistic possibilities generated by computer-based images. In Game-play he explores ideas of simulation and reality involved in the bombing of Iraq during the 1991 Gulf War, incorporating graphics from a computer game, F-19 Stealth Fighter, and photographs of Byzantine mosaics.

This particular work was conceived after hearing Bush talk about bombing around the clock seven days a week. It struck me that the whole action taking place was just like a Computer Fighter Simulation yet the stakes included historic and religious monuments It was a Cinerama type War fought by technicians and tacticians from behind a computer screen.

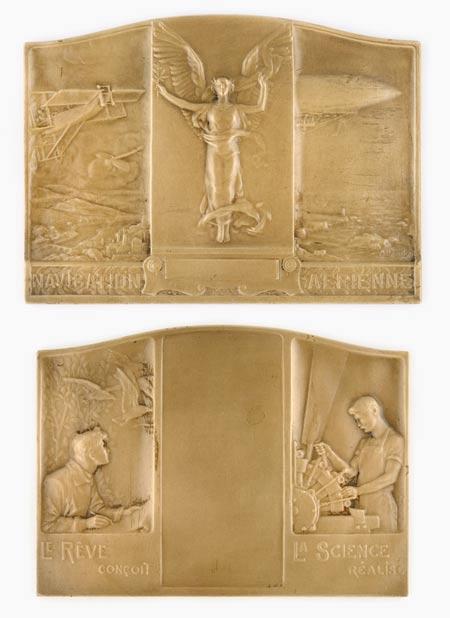

Raoul Benard

Versailles peace treaty, 1919

Pierre Morlon

Aerial navigation: science realises the dream of flight