Up front: faces of Australia at war: catalogue essay

- Commissioned works: First World War

- Commissioned works: Second World War

- Non-commissioned works

- Photographs

- Prisoners-of-war

- Propaganda

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Works and items exhibited

Death and absence are universal conditions of war. For those left behind and for those going off to war, the art of portraiture offers one way of overcoming these separations: portraits render a subject eternally present.[1] In this sense, war provides ideal conditions for portraiture to flourish.

George Coates and Dora Meeson -General William Bridges and his staff watching the manoeuvers of the 1st Australian Division in the desert in Egypt, March 1915

Portraits made in response to war also have other functions. They are a primary means of publicly commemorating military heroes and leaders; they are used to assert personal and national identities at times of war; they can be a vehicle for the expression of critical views about the nature of war itself.

Up front: faces of Australia at war presents a selection of portraits by artists created in response to the Australian experience of war from the 1890s to the present day. As portraiture is an activity not limited to the work of professional artists, Up front also includes examples of other forms of wartime portraiture, including posters, photographs and objects of personal use.

The subjects of the portraits in Up front are extraordinarily diverse: military heroes and leaders, ordinary men and women on active service and on the home front, prisoners of war, allies and enemies, as well as civilians. While these portraits tell us individual stories and illustrate the diverse experiences of war, lives and experiences are not the principal subjects of this essay; rather, it explores the various contexts in which the portraits in this exhibition have been made and used. These contexts range from commissioned works intended for public display to intimate portraits made for friends and family.

Since its beginnings the Australian War Memorial has played a major part in the commissioning of portraits recording Australians at war. This includes both the portraits made in the field by the official war artists during the period of their appointments, as well as specific portraits commissioned by the Memorial, usually after a war's conclusion, to commemorate important figures. This representation of a nation's people at war has also taken part in the conscious shaping of an Australian identity.

The first portraits acquired by the Australian War Memorial were made by the official war artists during the First World War. From 1917 onwards, following the example of the Canadian and British governments, fifteen artists were appointed to depict the war. For this war, as for subsequent conflicts, the official artists were put in uniform and given honorary commissions as officers. This gave them the status needed to move about freely in battle zones.

At this time there was no overall policy directing the collection of portraits, although several of the official artists who had established reputations as portrait painters (George Bell, James Quinn and John Longstaff) were instructed to make formal portraits of senior army officers. Portraits of a broader representation of the members of the Australian Imperial Force are however notably absent in the work of the official artists.[2] The principal exception is George Lambert who was appointed to cover the activities of the Australian forces in the Middle East. Lambert produced many drawings and watercolours, depicting not only senior officers, but also ordinary soldiers, nurses and voluntary workers. Lambert also made numerous drawings of local inhabitants, such as An Egyptian girl, a work that can be seen both within a broader artistic tradition of "Orientalism", as well as a reflection of the Australian soldier's tourist vision of Egypt.[3]

It was not until after the First World War that the Australian War Museum (as it was then known) began a systematic program of commissioning portraits for display in the as yet unbuilt museum. The concepts underlying this program would set the pattern for the commissioning of portraits for the Australian War Memorial through to the Vietnam War. These beliefs closely conformed to concepts underlying the establishment of national portrait galleries during the 19th century. These were conceived as places where images of those individuals, who had made outstanding contributions to the development of the nation and society, were displayed for the edification of the public.

The Australian landing at Gallipoli and participation in the First World War are events popularly considered central to the development of a sense of Australian nationhood. Only a year after the landing, an editorial in the Sydney Morning Herald wrote: "At the landing many fell, but the rest climbed the steep slopes - climbed up and up - climbing to a place among the nations…They made a new Australia."[4] The people to be depicted within the Memorial's portrait collection were there - foreseen as significant not only within a military context, but also as the "creators" of the nation.

In April 1920, H.S. Gullett, director of the Museum, wrote to the Minister of Home and Territories requesting funds to commission thirteen portraits to add to the collection. Gullett informed the minister that the Museum's existing collection was deficient, as it was limited to senior army officers and did not include portraits of "representatives of the Royal Australian Navy, the Australian Flying Corps, the Australian [Army] Nursing Service and non-commissioned officers or men." Gullett recommended that the subjects of these additional portraits should be "Australians who, by reason of their merit-odious service, may be considered qualified to represent in the national collection the arm or service with which they served."[5] Gullett's expressed purpose for these portraits was twofold: they would represent particular distinguished individuals, and also symbolically represent all members of the branch of the armed forces to which that individual belonged.

This duality of purpose was in fact paradoxical, as became evident to John Treloar, Gullett's successor as director. Even with the additional portraits, he was not satisfied with the representation of ordinary servicemen which was to have been provided for by three portraits of "non-commissioned officers or men" on Gullett's list. Although these were to be of "those who are typical of the force they will represent in our collections"[6], all three individuals chosen were Victoria Cross recipients, and thus exceptional rather than typical members of the armed services.

In January 1921 Treloar suggested to the Museum's management committee that further representations of the non-commissioned ranks should be included in the collection; moreover, he suggested that "Instead of providing for this by a few portraits of distinguished men such as VC winners it is proposed to secure a small series of character studies." Treloar did not intend these works to be portraits of specific individuals, but that they should depict a generic figure "in a sitting as regards pose and surroundings typical of the work of the arm of the service concerned."[7]

Charles Bean, a member of the committee, while agreeing that these would help "to dilute our gallery of Brigadier Generals (for which I realise I am largely responsible)"[8], did not favour Treloar's suggestion. Although several of these character studies were in fact commissioned, the committee's solution was simply to increase the number of portraits in the collection. At the committee meeting in April 1923, it was agreed to create a separate portraits sub-committee to recommend fifty individuals who were "entitled to this honour". [9] It was agreed that this list (referred to as the "hanging" list) should proportionately represent all branches of the services and most significantly, comprise approximately equal numbers of senior officers above the rank of lieutenant colonel, with the remainder being made up of junior officers and other ranks. Only individuals who had distinguished themselves on active service were to be considered.

To commemorate senior officers was simply a continuation of a long military tradition. However, with the exception of the divisional commanders, the senior officers who were chosen were not selected solely because of their rank, but for the quality of their leadership. This aspect of their service was also emphasised in the Memorial's first guide book to the collection; for example, the entry for the portrait of General Birdwood asserts: "His power of leadership sprang from an exceptionally kindly nature, which looked upon men as men, and he never made the mistake of setting before them low or selfish ideals… Sometimes he asked too much of them, but he always asked it for a worthy reason - the general good for which the allies were fighting."[10]

In addition to individual portraits, the committee also recommended the commissioning of three large-scale group portraits of senior figures engaged in significant historical events, including General William Bridges and his staff watching the manoeuvres of the 1st Australian Division in the desert in Egypt, March 1915, by George Coates and Dora Meeson. Although this work represents an actual event, two of the figures depicted were not present at the time, but included in the painting in order for it to be a complete representation of the leaders and staff of the Australian division that landed at Gallipoli.

This work thus depicts the command structure in the act of planning the most significant - in terms of national consciousness - Australian campaign. It portrays these leaders as literally far-sighted, as they plan for the landing and, by extension, the new nation.

It was the individuals in the "junior officer/other ranks" category, who were to represent the service of the ordinary serviceman. In the First World War this almost certainly meant a voluntarily enlisted citizen. As these men were selected primarily on the basis of bravery awards and were considered "heroes", their portraits explicitly reinforced the notion of the citizen's duty to the nation, by representing individuals who had so well discharged that duty.

In October 1923, the committee approved a list of 61 individuals who were to be represented. The Australian War Memorial (to which the Museum had now changed its name) was particularly concerned with obtaining the best quality portraits, artistically, for its collection and created an art committee to oversee the appointment of artists and placement of commissions. Bernard Hall, Director of the National Gallery of Victoria, was appointed artistic adviser. Obtaining an accurate likeness was also paramount, and in the several instances where the subjects of the portraits were deceased, the committee went to great lengths to supply the artists with photographs. Finished portraits were also referred to people who had personally known the subject for an opinion on its likeness.

The artists selected by the art committee for these commissions were academic painters with well-established reputations such as John Longstaff, George Coates and W.B. McInnes. All of the artists chosen worked within the stylistic conventions of tonal realism, favoured in the formal portraiture of the time. With few exceptions these portraits are characterised by a uniformity of composition in which all sitters are shown half-length against a dark and non-specific background.

The primary purpose of these portraits was to depict the subject in terms of their public identity, and the formality of the mood is deliberate. The sitter's public persona was presented by depicting the individual in uniform wearing the full entitlement of awards and medals, a requirement specified by the art committee. For the viewer, who in this period was generally well versed in military insignia, the uniform would signify the subject's military status, and the medal group could be read as a record of the sitter's war service and achievements. Individual personality was generally presented in keeping with this public role. George Coates' portrait, Captain Albert Jacka, depicts Jacka in a confronting stance, with both hands on hips. He is portrayed as full of confidence, a "man of action", consistent with his public identity as the most celebrated Australian martial hero of the First World War.

The process of executing these commissions continued well into the 1930s but was never finished. Due to funding shortfalls as a result of the Depression, and ultimately the onset of another war, only 45 of the planned 61 portraits were completed.

Commissioned works: Second World War

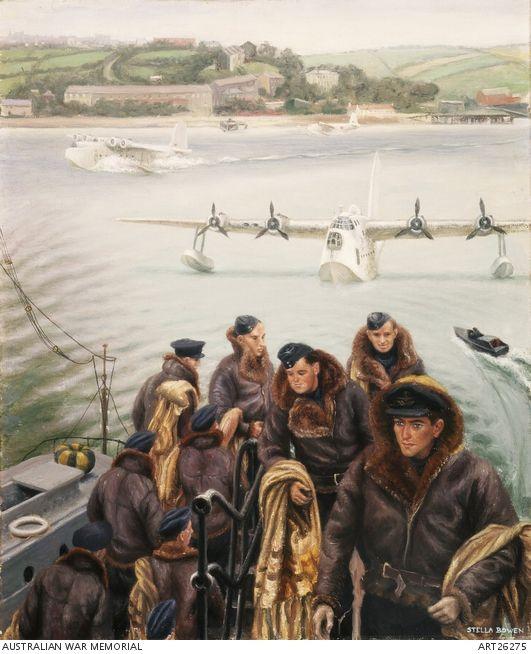

Stella Bowen - A Sunderland crew comes ashore at Pembroke Dock

With the outbreak of the Second World War, the scope of the Australian War Memorial was extended to include the representation of this war as well and it was decided again to appoint official war artists. Treloar, who had been seconded from the Memorial to head the army's Military History and Information Section which was responsible for coordinating the activities of the artists, was still concerned with the inadequacy of the representation of a broader range of individuals within the Memorial's collection.

In October 1941, with the first of the official artists already in the field, Treloar requested that the Memorial's management formulate a policy on portrait commissions and portrait collection. Treloar proposed two kinds of portraits, the first being of senior officers, "those in which the interest of the portrait lies in the importance of the subject", which he recommended should only be undertaken with specific instructions. This was to control the flow of these portraits into the Memorial's collection, as well as making it possible for artists in the field to refuse requests from "thrusters". Treloar continued that "There is another type of portrait where the artist should be allowed some freedom. These are the portraits of interesting heads painted on the spot simply because of their interest and not with any idea of immortalising the individual. [The artist Ivor] Hele has done two of this type… and I think they may be regarded as the best of his works."[11]

Both recommendations were endorsed and the board noted that as few as possible of Treloar's first category of portraits were to be painted during the course of the war. However, artists were actively encouraged to obtain the second category of portraits. Treloar's cabled instructions to be relayed to the official war artist Colin Colahan express what Treloar had in mind: "Some head studies of interesting or characteristic types [of] officers [and] other ranks in three services desired[.] [T]hese are not [to be] studio portraits and when exhibited names [of] sitters will not be shown but artists should supply names for records."[12]

In this way Treloar hoped to achieve the broad representation of ordinary Australians that the First World War collection lacked. Unlike Treloar's earlier concept of generic character studies, these were to be portraits of specific individuals; however by exhibiting them with only generic titles - such as "Infantryman", or "Nursing Sister" - Treloar intended that they would represent this wider group.

During the course of the Second World War, over 40 official artists were appointed, working in a far greater diversity of artistic styles than the First World War artists.[13] Treloar's encouragement of the artists to follow their own interests in finding subjects who appealed to them resulted in an extraordinary collection of portraits coming into the Memorial's collection during this war.

These portraits are not confined to rapid 'on-the-spot' recordings that Treloar's cable to Colahan implied. For example Stella Bowen's group portraits, such as Sunderland Crew comes ashore at Pembroke Dock, are carefully worked out compositions for which she made many preliminary studies before commencing this work in her studio. The breadth of subjects depicted in these portraits probably exceeded Treloar's expectations. As official artists covered all theatres of war and also the home front, their work includes portraits of members of virtually all branches of the services, both on active service and behind the lines, members of voluntary organisations, as well as civilian workers also engaged in the war effort. This represents a significant broadening of the concept of what constitutes service to the nation in wartime since the First World War, when only those "distinguished in active service" were portrayed.

Those now commemorated included members of groups within society, in particular women, who had for the first time been extensively mobilised as part of the "all-in" war effort. The official war artists also portrayed Aborigines, both those working in war industries as well as those enlisted in the services. These portraits, particularly within the context of the Memorial's collection representing the nation of Australia at war challenge the predominant contemporary representation of the typical Australian as being male and from a British background.

In many such portraits the artists attempt to bestow importance onto their otherwise quite ordinary sitters. Douglas Watson employs the profile format, traditionally associated with depictions of the nobility and rulers, for his portrait of George Bowles, the elderly sergeant serving in an administrative capacity at the Military History Section in Melbourne. Similarly a comparison between the initial drawing and the painting WAAAF cook (Corporal Joan Whipp) shows how Nora Heysen has exaggerated the cook's powerfully built arms and increased her relative size within the picture to make her a more imposing presence. Whereas the drawing probably captures what Heysen remembers of her character - "she was such a jolly person, and she got on very well with the men and she was such a good cook"[14] - in the painting she is depicted as serious and even formidable.

For many of the official artists, particularly those serving in New Guinea, the commissions provided their first contact with a people whose culture and appearance was so markedly different from their own, and many artists were drawn to this subject.

As Australia's wartime allies, their depiction fell within the scope of the official war artists' commissions. Their portraits such as Sali Herman's Kana Suani, Bougainville almost invariably depict their subjects within a framework of the exotic and reflect romantic notions about the supposed simplicity and idyllic way of life of these people.[15] Similarly, Herman's landscapes depict Bougainville as a tropical Garden of Eden.

The "enemy", particularly the Japanese, became another group of subjects which many of the official war artists depicted. These works are mostly of Japanese prisoners of war immediately after the end of the war. Depending on the attitude of the artist, these portraits range from works that depict the sitter's individuality and thus humanise the subject, to portraits such as Ralph Walker's Japanese engineer, Rabaul, that refer to previous stereotypical representations which caricature racial features. In October 1945 Eric Thake made a series of eleven drawings of Japanese prisoners on Timor entitled The face of Japan. These drawings, while depicting clearly identifiable individuals, are primarily a classificatory study of the Japanese face, representing distinctive versions of a basic physiognomic structure. For Thake they were intended to be a record "of the men against which the Australians fought"[16] and thus quite literally give a face, or several versions of it, to what had been the enemy.

After the Second World War, the Memorial decided to follow the precedent established after the First World War and commission portraits of selected distinguished individuals, but increase the proportional representation of both the navy and air force.[17] However Treloar suggested that the total number of portraits be limited to forty, as "experience in connection with the 1914-18 war suggests that the outstanding figures whose names remain in the public memory are few in number."[18] The process of selecting individuals proved extremely problematic and was not finalised until December 1954, by which time the number had been increased to 58 names.

Again during both the Korean and Vietnam Wars, the Memorial appointed official artists, although on a much reduced scale. The policy regarding the content of portraits continued unchanged from the Second World War throughout these conflicts, with "types" made in the field, and official commissions placed afterwards.

Non-commissioned works

Art concerning the creation of national identity through war has not of course been confined to the products of official commissioning schemes such as the Memorial's. In particular, the ANZAC legend has been re-interpreted by artists constantly throughout the last nine decades. Probably no other artist has explored this theme as comprehensively as Sidney Nolan. For Nolan the ANZAC legend was central to an under-standing of Australian identity: "Gallipoli is the great modern Australian legend, the nearest thing to a deeply felt, common religious experience shared by Australians."[19] Nolan produced works on this theme between 1956 and 1962, and again in 1977. Within this series he made hundreds of drawings of Gallipoli soldiers, as well as several large-scale paintings including Arthur Boyd and Kenneth. These works are not portraits of actual First World War Gallipoli soldiers, but were titled after two of Nolan's friends who had both served during the Second World War. In the case of Kenneth, it was Nolan's wife Cynthia who, viewing the work after it had been completed, commented that it looked like their friend Kenneth von Bibra, who had been killed in Syria in 1941. In this way, Nolan extended the ANZAC legend to encompass the men of the Second World War.

Artists have also used the genre of portraiture as a way to express their personal responses to war, as well as to present critical discourse about war and its effects on individuals, including both civilians and combatants.

One example of this type of portrait is A mother of France, by the Australian expatriate artist Hilda Rix Nicholas. It is a portrait of her elderly neighbour in the French town of Étaples, whose son had been killed in one of the early battles of the First World War.[20] Nicholas portrays this woman as consumed by her private grief, an image that counters contemporary rhetoric that mothers should take pride in their sons' sacrifice for their country. By only identifying the woman as a mother of France, Nicholas presents her as a symbol of the suffering of all mothers who had lost their sons at war.

Kevin Connor's works from the Gulf War are similarly concerned with individual suffering as a result of war and the impact of war on the civilian population. Kevin Connor travelled to Iraq in 1991, several months after the end of the Gulf War. His portfolio of sixty drawings, Iraq June 1991, contains numerous portraits including several self-portraits. In A man whose family died when his house was bombed in a Basrah suburb, Connor brings us into direct contact with this man's anguish, as well as referring to its cause. Within the portfolio, Connor's self-portraits refer to his awareness of his status as outsider and observer of this human tragedy, and declare the subjectivity of his artistic consciousness.

Both Albert Tucker's and Trevor Lyons' portraits are examinations of the effects of war on combatants. In 1942 Albert Tucker was drafted into the army and soon after sent to Heidelberg Military Hospital for treatment of a minor illness; his Psycho, Heidelberg Military Hospital is a portrait of a psychiatric patient confined there. Tucker explains: "[I] had been placed in a ward next to the 'nut' ward. The ambulances used to arrive in the middle of the night with various poor blokes who had gone off the rails for one reason or another. It was a brief image in the night as he jumped out of the back door, wide eyed and staring like a zombie… One of the unsung casualties of war."[21]

For Trevor Lyons, the self-portrait has been the site through which he has explored his own experience of war and its on-going effects. A career soldier, Lyons received severe facial injuries from an exploding landmine while serving in Vietnam, for which he underwent major reconstructive surgery. His suite of 22 etchings, entitled Journeys in my head, chronicles a process of physical and psychological disintegration of the self as a result of the wounds sustained in Vietnam.

Portraits have a long history of being used to commemorate and remember the dead. Amongst the most intimate of such portraits is John Longstaff's Portrait of my son (Lieutenant John (Jack) Longstaff). It is a portrait, made posthumously, of his son who was killed on the Western Front in 1916, whose body was never found. Longstaff has portrayed his son in uniform, the wearing of which was ultimately responsible for his death. However, by choosing to remember his son in this way, Longstaff accepts his son's death as an act of patriotic sacrifice. This work is inscribed on the back "not to be sold" indicating its intense personal significance for the family.

Similarly, after the First World War many homes of Australian families who had lost a family member in the war contained private memorials to these individuals. Typically, these consisted of a framed combination of elements such as a photographic portrait, the individual's medals, the bronze next-of-kin plaque with accompanying scroll from the sovereign, King George V, as well as text detailing the individual's war service and circumstances of death. These personal shrines consoled those left to grieve by presenting the individual's death as being for "king and country", and served as a focus for private remembrance. This was particularly important in Australia, where out of the 60,000 killed during the First World War, only one body was brought back for burial.

Artists have traditionally exchanged works of art, including portraits, with each other, both as a mark of respect for each other's work and as tokens of their friendship. In 1947 Albert Tucker travelled to Japan as a war correspondent accredited to the British Commonwealth Occupation Force where he met several former Japanese war artists.[22] Tucker made portraits of these artists, and in the case of Inokuma Genichiro made two similar drawings, one to present, and one to keep for himself. At least one of these artists, Sanda Yasushi, made a portrait of Tucker as a gift. This friendship exchange of portraits is particularly significant as it was made only two years after the end of the war, after the atom bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the revelations in Australia of the Japanese treatment of Allied prisoners of war.

Photographs

Of course, the vast majority of portraiture made in response to war is photographic and includes both the work of amateur photographers and that of commercial photography studios. The various types of these photographic portraits have remained remarkably consistent in terms of imagery and functions in this century.

With the advent of the lightweight camera and nitrate film at the end of the 19th century, informal, intimate snapshot photography has become this century's most ubiquitous type of portraiture. The men and women who served in the First World War travelled with their cameras, and their successors have continued to do so ever since. The resulting portraits of the self and close friends record participation in significant events or experiences of new places. These are private souvenirs of the amateur photographer's experience of war and often have the feel of tourist photography.

During the First World War it became almost universal practice to have a formal studio photograph taken in uniform. Some commercial photography studios, such as the Darge Studio of Melbourne, even set up concessions at training camps such as Broadmeadows to cater for this demand. In some cases, individuals who had not yet been issued with their own uniforms were photographed in uniforms supplied by the studio, even if it was not the correct uniform of the branch of the services in which they had enlisted. It was to be recorded in uniform that was important, for being in uniform signified patriotism and fulfilment of duty. Photographs of oneself in uniform can also be seen as marking the transition from citizen to soldier; they affirm the new identity. These images inevitably found their way home to be displayed on the mantelpiece as a representation of the absent son or husband, and to indicate the sacrifice that the family itself was making.

Another type of portrait photography common to all wars is the formal group portrait of military units. The size of these groups can vary from the handful of crew members of one aircraft, to an entire ship's crew or infantry company consisting of over one hundred men. These photographs constitute the individual as a group member and reflect both the importance of this group to the individual and the place of the individual and group in the military hierarchy.

Prisoners-of-war

Portraiture was widely practiced by prisoners in German concentration camps during the Second World War, as these pictures could offer "a hope of permanent presence among the living, a matter of profound significance for people whose temporal existence was so fragile."[23] Portraits were made in POW camps for similar reasons. Jim Collins' series of portraits, his "rogue's gallery" as he referred to them, were made while he was a member of A Force, a group of Allied prisoners of war forced by the Japanese to construct the Burma-Thailand Railway. By the beginning of 1943, many prisoners had died and it was clear to their senior officer, Brigadier Arthur Varley, that the casualties were going to become much worse. In order to make a record of these men, Varley was able to provide Collins, who possessed rudimentary drawing skills, with basic drawing materials and instructed him that these "were to be used for drawing portraits of fellow POWs, some of whom would not survive the war."[24] By the end of the war Collins had completed almost 100 portraits, all of which had been made covertly, for detection by the Japanese would have resulted in severe punishment. The majority of these works include the sitter's name and the address of his next of kin. The intention, however, was not to give the portraits to relatives but to keep the collection together as a memorial to those that had died and to the suffering of the survivors.

Propaganda

Wartime propaganda has also used images of significant personalities to further a cause. Most commonly these are of military or political leaders. However, during the First World War, the image of Albert Jacka, the first Australian to be awarded the Victoria Cross at Gallipoli, was used extensively on recruiting posters. Wartime portrait images have also been used on a variety of objects for personal or domestic use such as tea sets, scarves and lapel buttons, serving as expressions of patriotism.

Conclusion

As separate works, the portraits in Up front tell a variety of stories and reflect the range of individual experiences during war. As a collection of works, they also tell other stories: they illustrate the changes in this century in whom we as a nation choose to commemorate; they reveal what we value in ourselves and in others; they represent the variety of purposes portraits have served during wartime - affirmation of new personal or national identities, remembrance of loved ones, mourning for the dead.

Elena Taylor

Australian War Memorial

Notes

1. J. Woodall (ed.), Portraiture: facing the subject, Manchester, 1997, p. 8.

2. Although Will Dyson's drawings from the Western Front are overwhelmingly about the human condition of war, with few exceptions they are not portraits of specific individuals, but depict generic "digger types".

3. Richard White, "The soldier as tourist: The Australian experience of the Great War" in A. Rutherford and J. Wieland (eds), War: Australia's creative response, Melbourne, 1997, pp. 116-129.

4. Quoted from K.S. Inglis, "The Australians at Gallipoli" in Historical studies 21: 84 (April 1985) 373.

5. H.S. Gullett to Senator A. Poynton, 27 April 1920, AWM 93 18/4/34.

6. Treloar to Bean, 20 May 1920, AWM 93 18/4/34.

7. Treloar to Bean, 17 January 1921, AWM 93 18/2/8.

8. Bean to Treloar, 2 March 1921, AWM 93 18/2/8.

9. Minute of Australian War Museum Committee meeting, 4 April 1923, AWM 93 18/4/10.

10. Guide to the Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1941, p. 14.

11. Treloar to T. Heyes [AWM Acting Director], 3 October 1941, AWM 93 895/2/11 pt 1.

12. Treloar to A. Bazley [AWM Acting Director], 12 June 1942, AWM 93 895/2/11 pt 1.

13. During the Second World War other government agencies also set up art commissioning schemes closely modelled on the Memorial's. The RAAF and the Allied Works Council each appointed official artists; their inspired choices included Eric Thake and William Dobell respectively.

14. Nora Heysen interviewed by Cathy Speck, 15 September 1989, quoted from Cathy Speck, "Australian women war artists', PhD thesis, Department of Visual Arts, Monash University, 1996, p. 397.

15. Corporal Kana Suani served in the Royal Papuan Constabulary and was decorated for rescuing an Australian soldier while under heavy enemy fire.

16. Quoted from Andrew Sayers, "Eric Thake and the face of defeat" in Journal of the Australian War Memorial 21 (October 1992) 53.

17. Quite incredibly, given the importance of the women's services during the Second World War, this list did not include any representatives of the women's services, while the First World War list had included the Matron-in-Chief of the AANS. At a meeting of the Board of Trustees in July 1963, it was noted that this "omission" had been the cause of a number of inquiries, and it was decided to select Nora Heysen's 1944 portrait of Matron Annie Sage to represent the women's services.

18. Treloar to General T. Blamey, 13 April 1949, AWM 93 895/2/11 pt 1.

19. Quoted from Charles Spencer, 'Myth and hero in the paintings of Sydney Nolan', in Art and Australia 3:2 (September 1965) 95.

20. The dating of this work is problematic. I have followed information given by Rix Nicholas's son about the subject to date it as c. 1914. Rix Wright to Anne Gray [AWM Senior Curator of Art] 18 May 1981, AWM 93 895/3/69. See also Speck p. 191 for a discussion of alternative datings.

21. Albert Tucker to Gavin Fry, quoted in Gavin Fry and Anne Gray, Masterpieces of the Australian War Memorial, Adelaide, 1982, p. 70.

22. Tucker met and made portraits of Fujita Tsuguharu, Inokuma Genichiro, Wakita Kazu, Ogisu Takanori, and Sanda Yasushi.

23. J. Blatter and S. Minton, The art of the Holocaust, London, 1982, p. 28.

24. Jim Collins AWM 93 895/4/28

Works and items exhibited

All works and items are in the collection of the Australian War Memorial, unless otherwise noted.

Measurements are in centimetres, height precedes width.

Compiled by Magda Keaney

Tibor Binder (b. 1923)

Árpárd Malinovsky 1945

watercolour over pencil 32.6 x 25

presented in 1973

(27841)

D. Roth 1945

watercolour over pencil 30.9 x 22.8

presented in 1973

(27834)

B.C. Boake (1838-1921)

New South Wales Contingent, Sudan Campaign 1885

albumen silver photographs, oil on canvas 175 x 226

acquisition details unknown (H19467)

Stella Bowen (1893-1947)

A Sunderland crew comes ashore at Pembroke Dock 1945

oil on canvas 76.2 x 63.4

acquired under official war art scheme in 1946

(26275)

Flying Officer Frederick (Derry) Syme, Captain 1945

oil on academy board 30.6 x 22.8

acquired under official war art scheme in 1946

(26281)

Pilot Officer Ronald Warfield, Navigator 1945

oil on academy board with pencil 30.6 x 25.4

acquired under official war art scheme in 1946

(26278)

Private, Gowrie House 1945

oil on academy board 30.4 x 25.4

acquired under official war art scheme in 1946

(26277)

George Coates (1869-1930)

Captain Albert Jacka 1921

oil on canvas 76.8 x 63.3

acquired under commission in 1922

(201)

George Coates (1869-1930) and Dora Meeson (1869-1955)

General William Bridges and his staff watching the manoeuvres of the 1st Australian Division in the desert in Egypt, March 1915 1922-26

oil on canvas 116.9 x 160.3

acquired under commission in 1927

(9425)

Colin Colahan (1897-1987)

Workshop decor (Flight Sergeant Bruce Love) 1942

oil on canvas 61 x 51

acquired under official war art scheme in 1944

(26360)

Kevin Connor (b. 1932)

The chemist 1991

gouache 38.3 x 57.5

presented in 1992

(29752.008)

Self-portrait, drawing in Iraq 1991

gouache, brush and ink and wash with blue crayon 37.9 x 56.5

presented in 1992

(29752.051)

A man whose family died when his house was bombed in a Basrah suburb 1991

brush and ink and wash and red crayon 41.9 x 59.2

presented in 1992

(29752.048)

The deserter, Baghdad 1991

brush and ink and wash 42 x 59.2

presented in 1992

(29752.009)

Peter Corlett (b. 1944)

maquette for Simpson and his donkey 1915

1986

unique cast bronze 41.5 x 25 x 36

purchased in 1986

(40983)

Sybil Craig (1901-89)

Handing over a respirator (Ruby Wilks) 1945

coloured pastels 81.3 x 56.5

acquired under official war art scheme in 1945

(26119)

Chargewoman McGillivray soldering (Stasia McGillivray) 1945

oil on canvas on plywood 36.6 x 26

acquired under official war art scheme in 1945

(22605)

Assistant monitress, Detonator Section (Sylvia Wood) 1945

pen and brown ink 35.6 x 28

acquired under official war art scheme in 1945

(22595)

Monitress in her office (Merrin Wilson) 1945

pen and ink 32.3 x 25.6

acquired under official war art scheme in 1945

(22596)

William Dobell (1899-1970)

Cement worker, Sydney Graving Dock [c. 1943]

oil on cardboard 76.2 x 50.8

presented in 1945

(30249)

Max Dupain (1911-92)

Clem Searle and Robert (Bob) Emerson Curtis, Goodenough Island 1943

gelatin silver photograph printed in 1998 from original negative in Dupain archive

33.5 x 25

duplicate negative

acquired in 1995 (P02186.004)

print purchased in 1998

(P02683)

Will Dyson (1880-1938)

D Mess, 1st ANZAC Corps Headquarters, Henencourt 1917

crayon 45.7 x 34.9

acquired under official war art scheme in 1919

(2359)

Work done, Bazentien [c. 1917]

crayon with pencil 54 x 43

acquired under official war art scheme in 1919

(2218)

Donald Friend (1915-89)

Soldier resting 1945

oil on canvas 61.2 x 46

acquired under official war art scheme in 1946

(22899)

George Gittoes (b. 1949)

Corporal Mortimer wearing camouflage headdress, Somalia 1993

cibachrome printed in 1998 from original transparency 21.5 x 32.5

transparency acquired in 1993 (P1735.471)

Corporal Julie Baranowski on patrol, Somalia 1993

cibachrome printed in 1998 from original transparency 21 x 32.5

transparency acquired in 1993 (P1735.010)

Australian soldier at a village bar, Cambodia 1993

cibachrome printed in 1998 from duplicate transparency 21.5 x 32.5

transparency acquired in 1993 (P1744.138)

Ivor Hele (1912-93)

General Thomas Blamey 1941

oil on canvas 91.4 x 76.2

acquired under official war art scheme in 1941

(28252)

Sergeant Thomas (Diver) Derrick 1944

oil on canvas 91.3 x 76

acquired under official war art scheme in 1944

(24071)

Sergeant John Parker 1952

coloured crayons, carbon pencil on paper 56.2 x 37.8

acquired under official war art scheme in 1952

(40339)

Private Edward Fergus 1952

charcoal with crayon 55.9 x 37.9

acquired under officialwar art scheme in 1952

(40409)

Sali Herman (1898-93)

Kana Suani, Bougainville 1945

oil on canvas on plywood 45.4 x 40.5

acquired under official war art scheme in 1945

(22849)

Nora Heysen (b. 1911)

WAAAF cook (Corporal Joan Whipp) 1945

oil on canvas 82.4 x 64.4

acquired under official war art scheme in 1945

(24394)

Corporal Joan Whipp 1945

coloured crayons 50.2 x 32.6

acquired under official war art scheme in 1945

(24272)

Louis Kahan (b. 1905)

Corporal James L. Corbett 1944

pencil 28 x 21.3

purchased in 1988

(29350)

M.L. Ridgley 1944

pencil 28.2 x 21.8

purchased in 1988

(29355)

George Lambert (1873-1930)

Arthur Streeton 1917

oil on canvas 76 x 63.5

purchased in 1983

(19841)

Mrs Alice Chisholm of Kantara 1918

pencil 35.4 x 24.5

acquired under official war art scheme in 1919

(2756)

Captain Hugo Throssell 1918

pencil 31.8 x 23.7

acquired under official war art scheme in 1918

(2797)

An Egyptian girl 1918

watercolour with pencil 35.4 x 25.4

acquired under official war art scheme in 1918

(2794)

Sister Tidy, Australian nursing sister 1919

pencil 25 x 16.6

acquired under official war art scheme in 1921

(2867)

John Longstaff (1862-1941)

Portrait of my son (Lieutenant John (Jack) Longstaff) 1916

oil on canvas 61 x 51.2

presented in 1974

(19522)

Trevor Lyons (1945-90)

Journeys in my head: 2nd state 1987

etching 34.1 x 30.2

purchased in 1991

(45086)

Journeys in my head: 5th state 1987

etching with aquatint 34.2 x 30.1

purchased in 1991

(45089)

Journeys in my head: 8th state 1987

etching with aquatint 34.2 x 30.1

purchased in 1991

(45092)

Journeys in my head: 12th state 1987

etching with aquatint 34.1 x 30

purchased in 1991

(45096)

Journeys in my head: 18th state 1987

etching with aquatint 34 x 30

purchased in 1991

(45102)

Journeys in my head: 21st state 1987

etching with aquatint 34 x 30

purchased in 1991

(45105)

Ken McFadyen (1932-98)

Vietnamese awaiting interrogation 1967

charcoal 56 x 37.8

acquired under official war art scheme in 1968

(40639)

Crew member, HMAS Hobart 1967

charcoal 58.5 x 39.7

acquired under official war art scheme in 1968

(40656)

W.B. McInnes (1889-1939)

Captain Ross Smith 1920

oil on canvas 76.2 x 63.8

acquired under commission in 1920

(3179)

Paul Montford (1868-1938)

General John Monash 1938

unique cast of the second edition, original plaster [c.1928]

bronze 68 x 50.5 x 30

acquired in 1938

(13579)

Hilda Rix Nicholas (1884-1961)

A mother of France [c. 1914]

oil on canvas 72.6 x 60.2

purchased in 1922

(3281)

Sidney Nolan (1917-92)

Kenneth 1958

synthetic polymer paint on hardboard 122 x 91.5

presented in 1978

(19577)

Arthur Boyd 1959

synthetic polymer paint on hardboard 122 x 91.5

presented in 1978

(19578)

Tom Roberts (1856-1931)

Sergeant Robert Fraser of the New South Wales Mounted Rifles 1896

oil on kauri pine panel 62 x 28.2

purchased in 1974

(19505)

Infantryman of the New South Wales 2nd Infantry Regiment 1896

oil on kauri pine panel 62.2 x 28.3

purchased in 1974

(19506)

Sanda Yasushi (1900-68)

Albert Tucker 1947

pen and ink 38.2 x 27.6

presented in 1983

(28470)

Eric Thake (1904-82)

Lieutenant General Yamada Kunitaro 1945

pencil 38.2 x 33.1

presented in 1947

(26792)

The face of Japan No.2 1945

pencil 30.2 x 22.5

presented in 1947

(26794)

The face of Japan No.9 1945

pencil 30.5 x 22.8

presented in 1947

(26801)

Barbara Tribe (b. 1913)

Squadron Leader Bobby Gibbes 1968

unique cast of the second edition,

original plaster 1943

bronze 47.4 x 47.4 x 30

purchased in 1968

(27625)

Albert Tucker (b. 1914)

Psycho, Heidelberg Military Hospital 1942

carbon pencil, coloured wax crayons, brown pastel, gouache 25 x 17.9

purchased in 1979

(28305)

Inokuma Genichiro 1947

pen and ink and wash with charcoal 35.6 x 26.6

presented in 1983

(28471.02)

Unknown photographer

Studio portrait of Nancy Wake [c.1945]

gelatin silver photograph printed in 1998 from duplicate negative

19.6 x 13

negative acquired 1988

(P0885/01)

Ralph Walker (b. 1912)

Japanese engineer, Rabaul 1983

unique cast, original plaster 1948

bronze 44.5 x 22.5 x 20

acquired in 1983

(40922)

Napier Waller (1894-1972)

RAN! (Australian sailor) 1942

drawing for illustration in The Australasian, 21 November 1942

watercolour over pastel and pencil 75.8 x 56.2

purchased in 1980

(28344)

The digger of today (self-portrait) 1942

drawing for illustration in The Australasian, 12 September 1942

watercolour over pastel and pencil 76.2 x 57.5

presented in 1973

(27820)

Douglas Watson (1920-1972)

Sergeant George Bowles 1943

oil on canvas 45.4 x 39.4

acquired under official war art scheme in 1943

(22431)

Bryan Westwood (b. 1930)

Leonard Hall 1990

oil on canvas 61 x 53.5

presented in 1995

(90417)

Ernest Guest 1990

oil on canvas 61 x 54

presented in 1995

(90420)

SHOWCASE 1: SKETCHBOOKS

Frank Hinder (1906-92)

Lou, Darwin [c. 1944]

pen and ink 25.7 x 21.1

presented in 1988

(29316)

Sketchbook comprising twenty drawings, with cardboard cover and blue taped spine [c.1944]

pencil, pen and coloured inks 17.6 x 12.7

purchased in 1980

(28368)

George Lambert (1873-1930)

The buff book: sketchbook comprising ten drawings, with buff linen-covered board cover [c. 1918-1920]

pencil 24.2 x 32.0

purchased in 1930

(11392)

Francis Lymburner (1916-72)

Soldier [c.1942-1944]

pen and ink with wash 20.1 x 19.5

purchased in 1985

(28798)

Soldier [c.1942-1944]

pen and ink 11.8 x 19.8

purchased in 1985

(28824)

Sketchbook comprising seventy drawings with beige woven cover and maroon binding [c.1942-1944]

pencil, pen and ink and wash, brush and ink and wash

purchased in 1985

(28827)

SHOWCASE 2:

JIM COLLINS (1916-93)

Stan Chesworth [c. 1943-45]

pencil 17.1 x 13.5

presented in 1980

(28403.03)

O.A. Herbert [c. 1943-45]

pencil with coloured crayon and yellow wash 17.1 x 11

presented in 1980

(28403.35)

Warrant Officer A. McLean [c.1943-45]

pencil 18 x 13.4

presented in 1980

(28403.49)

Paddy Maloney [c. 1943-45]

pencil 17.6 x 13.2

presented in 1980

(28403.01)

Joe Mye [c. 1943-45]

pencil 17 x 10.8

presented in 1980

(28403.76)

Cor Punt [c. 1943-45]

pencil 17.4 x 13.4

presented in 1980

(28403.52)

Les Tolliday [c. 1943-45]

pencil 18 x 11.8

presented in 1980

(28403.31)

Brigadier Arthur Varley [c. 1943-45]

pencil 16.7 x 11.8

presented in 1980

(28403.09)

Lieutenant John Varley [c. 1943-45]

pencil 17.2 x 13.4

presented in 1980

(28403.48)

Replica of bamboo cylinder used to conceal drawings [c.1980]

made by Jim Collins

private collection

SHOWCASE 3

Place of manufacture is followed by date of manufacture.

South African War

Fundraising buttons: Australia [c. 1899-1902]

Lieutenant General Lord Kitchener (REL26398.001)

Major General Sir J.D.P French (REL26398.002)

Field Marshal Lord Roberts (REL26398.003)

General Sir R.H.Buller (REL26398.004)

Lieutenant General Sir G.S. White (REL26398.005)

Major General Sir H.A. MacDonald (REL26398.006)

Commemorative plate of Major General Sir J.D.P.French

United Kingdom

[c. 1899-1902]

(REL/18943)

First World War

HRH Princess Mary 1914 Christmas gift; embossed tin containing Christmas greeting card and photograph of HRH Princess Mary

United Kingdom 1914

(RELAWM10179)

Selection of cards from Euchim War Game

Australia [c. 1918]

(REL/21882)

Medallion commemorating the British Fifth Army's liberation of the French city of Lille, featuring an impression of General Birdwood

France [c. 1918]

(RELAWM09586)

Medallion commemorating the Battle of the Marne 1914

obverse: featuring impressions of Generals Joffre, Maunoury and Gallieni

reverse: Marianne encouraging French troops in the field

France [c. 1914]

(RELAWM09350.001)

(RELAWM09350.002)

Medallion featuring Charlotte, Countess of Itzenplitz, Women's National Club

Germany [c. 1914-1915]

(RELAWM01139)

Medallion featuring Wilhelm II, Emperor of Germany, King of Prussia

Germany [c. 1914-1918]

(RELAWM01145)

Second World War

Ternes

Your country needs you [c. 1940]

photolithograph

28 cm diameter

presented, date unknown

(V00301)

Fougasse (pseud. of Cyril Bird) (1887-1965)

Careless talk costs lives 1940

photolithograph

31.9 x 20.3

presented in 1946

(V02449)

Gulf War

Postcard featuring President Saddam Hussein and Prisoner of War

France 1991

(SC02027)

Postcard featuring General Norman Schwarzkopf

France 1991

(SC02028)

Postcard featuring General Colin Powell

France 1991

(SC02029)

Postcard featuring President George Bush and President Saddam Hussein

France 1991

(SC02030)

SHOWCASE 4

First World War

Ceramic frame containing photograph of Private Sydney Harold Banks-Smith

Australia [c. 1915]

(PROP01370) (P456/07)

Locket, containing photograph of soldier, engraved "From Max. With fondest Love.

Oct 24th 1916."

Australia 1916

(REL/08992)

Heart-shaped locket, containing photograph of soldier and lock of hair, inscribed "in memory of", in wooden box

Australia [c. 1914-1918]

(REL/10572)

Photograph printed as postcard of four mounted Australian soldiers in front of the Sphinx and the Great Pyramid, Egypt

Egypt [c. 1915]

(SC02031)

Photograph of Australian nurses sightseeing in Egypt

Egypt [c. 1914-1918]

(H16403)

Hand-coloured photographic miniature set in oval shaped pendant, in leather case

Australia [c. 1914-1918]

private collection

Photograph of a German soldier

Germany [c. 1914-1918]

private collection

Photograph of an Australian soldier

Australia [c. 1914-1918]

private collection

Memorial card for Corporal Llewellyn Rowland Jones

Australia 1918

private collection

Second World War

Memorial brooch in shape of RAAF insignia, containing photograph of Sergeant John Freeth

Australia 1944

(REL25225)

Pendant in shape of slouch hat, containing photograph of Private T. Graham

Australia [c. 1939-1945]

(REL/17468)

Group photograph of D Company, 2/29th Infantry Battalion, Bonegilla, Victoria

Australia 1940

(P1652.001)