'If we go, we may as well go together'

Bob Semple: "I’m yet to find a soldier that at some stage of his life was not frightened." Photo: Leigh Henningham

Ninety-seven-year-old Bob Semple knows all too well about war. His uncle was killed on the 25th of April 1915 as the Anzacs landed on Gallipoli. Ten of his mates are buried side by side in the desert of North Africa. And the names of his gun crew are carved into the back of the violin he took to war.

“Never ever forget,” he said quietly, looking off into the distance. “And I keep saying, there are more Victoria Crosses and other high awards buried under the sand of the desert of North Africa and in the mud of the Islands than there are that ever walked about on top of the earth. [They have] nothing against their names, but we know who they were.”

It’s mid-morning and Semple is sitting in the front room of his family home in the Melbourne suburb of Essendon, talking about the Second World War as he prepares to travel to Canberra this Anzac Day to speak at the National Ceremony at the Australian War Memorial.

It’s more than seven decades since the war, but for Semple, who turns 98 next month, the memories remain vivid. He still considers himself to be fortunate –fortunate to have survived six years of war, fortunate to have married the love of his life, and fortunate to have had a sense of humour and a passion for music that has helped him through it all.

He still has the violin he took away to war, along with the old felt hat and the greatcoat that he was given when he enlisted. They still fit, and the old violin case, marked with his initials and regimental number, still has sand in it from his time in the Middle East and North Africa.

“The old violin went into action,” he said with a laugh. “That’s the old case it was carted about with in the desert, but she’s a bit rough with the old desert sand in it. It got in everywhere, and I had to send [the violin] in for a bit of a polish and that to get it back into action after I got home…. It’s got my gun crew’s names scratched onto it, and it needs tuning, but I still pick it up. Music is the thing of mood really, and I’ve got sheets and sheets of music. I’ll open it up, and I can just sit there.

The name's of Bob Semple's gun crew are carved into the back of the violin he took away to war.

“My crew were blokes that were nearly all farmers and they were wonderful. What they could do with a piece of wire and all that sort of stuff… Well, I would not swap any one of those blokes for all the money in the world. It was a bond that could be even more powerful than your own wife or your own family, and that’s not being cruel, that’s just being honest.”

During the war, they would dig slit trenches behind their artillery guns and cram into them to try to protect themselves from “all the shrapnel that was flying around” as they watched the German dive bombers fly in to attack.

“I’m yet to find a soldier that at some stage of his life was not frightened,” he said. “But you have to discipline your feelings… [And] when the shells come over, they haven’t got Catholic, Protestant or Hebrew on them, I can tell you that.

“I’ve sat there many times, and the Stukas would fly in and roll over… We’d say, ‘Well, Peter, this looks like it,’ or Bill … and the three of us would be sitting there, and each one of us would put our hands up, and we’d hold each other’s hands. … Things like that, they’re just natural reactions. You do it because you’d say, well, if we go, we may as well go together.”

He will never forget his 10 mates who were killed by the same shell during the siege at Tobruk and are buried side by side in the desert sand. “They went out trying to dig another gun pit, so that they could fire some old 60-pounders that were engaging Bardia Bill, a big heavy German gun that was shelling the city,” he said. “They tried two or three times to get in, and some of those battles were pretty fierce, and we lost a lot of blokes, who were killed one way or another. Ten of them went off in one truck load and they were coming back from digging in a position. A German spotter plane came up … and they were hit by one shell…

“All of those things you’ve got to learn to live with, I suppose. It’s a soldier’s life.”

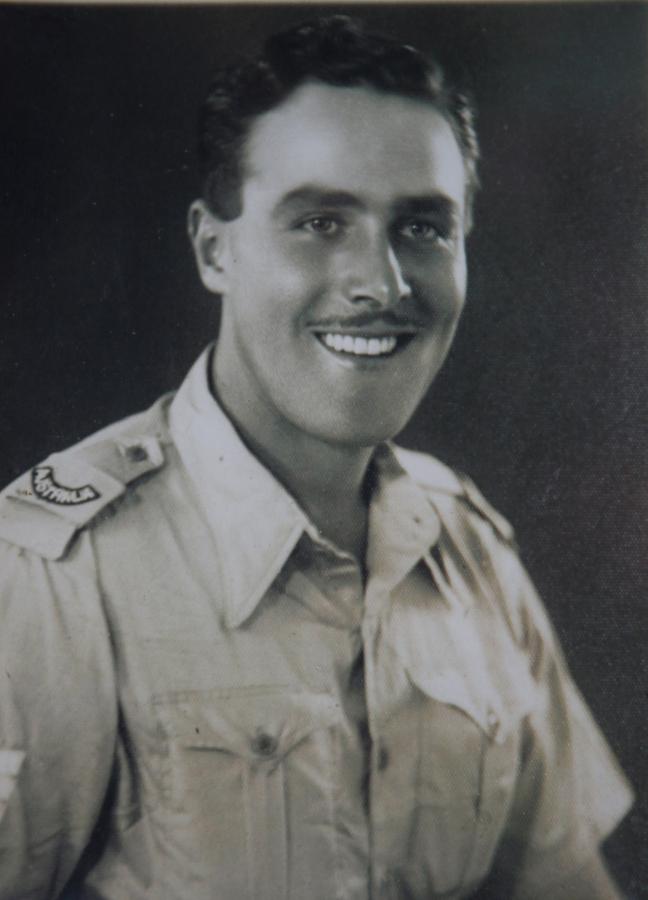

Bob Semple during the war: "It’s hard to explain to people now what it was like." Photo: Courtesy Bob Semple

It’s a long way from where he came from. The eldest of four children, Semple was born on 4 May 1920 in Essendon, the suburb in which he has lived his entire life. He grew up during the Depression years, playing “all sorts of sports”, but his mother Lottie was determined that he and his three younger sisters would learn music.

“It’s hard to explain to people now what it was like,” he said. “It was a different society … I didn’t even have a bike as a kid and I walked everywhere, but my mother loved the theatre and she said, ‘You’re going to learn the violin … because you will always be able to get a job if you can play the violin and some other instrument.’

“My [Scottish] grandfather, whose house we lived in, thought it would be a pretty good idea if I learnt the bagpipes [as well] … so I learnt to wrestle the octopus … and I used to bring out the practice chanter, and that’s how I got started in the bagpipes.”

It was to be the beginning of a lifelong love of music and the bagpipes, and at 16 he joined the cadet corps of the Victorian Scottish Regiment.

“The big burly Regimental Sergeant Major in charge of the depot said in broad Scots, ‘What do you blokes want?’ [When] we said, ‘We’ve come to join this regiment,’ he said, ‘Well, I’ve got news for you – get in the queue … and furthermore, you’ll have to buy your own kilt.’

“We said, ‘Hang on a minute, how much are these kilts?’ and he said, ‘3 pound 10’. Well, I started work at 8 and 6 a week … so [after] a couple of months, we begged, borrowed and stole two bob, and five bob, and 13 shillings, and anyhow, we paid the 3 pound 10. I’ve still got the kilt out in the shed … and I’ve still got the old receipt for it.”

He transitioned into the 5th Battalion of the Scottish Regiment when he turned 18 and played the bagpipes in the regimental band. “The battalion had red and black colours, which were Essendon’s colours, so I was happy,” he said with a laugh. “And everything was going right.”

When the war broke out, he was working in “the rag trade” for a company in Flinders Lane in Melbourne, and he heard the declaration of war on an old wireless. “I well remember it,” he said. “I was brought up in an atmosphere of respect for family, king and country, and I felt it was my duty to enlist. It was a war – a worldwide war – and it was only going to get bigger.”

Bob Semple wearing his hat and great coat from the war: "They hung a pair of boots around your neck with a string, and put a hat on your head, and gave you a coat and everything else." Photo: Leigh Henningham

His mother’s brother, Private John Adams, had been killed as the Anzacs landed on Gallipoli on 25 April 1915, and Semple was determined to join up. When the Scottish Regiment called for volunteers for overseas service, Semple was among the 800 men who turned out at Portsea. “The whole mob took a pace forward,” he said. “But they only picked a few of the officers… and then they sent us home for Christmas.”

Three months later they called for more volunteers at Mt Martha, but Semple and his mates missed out again. “We couldn’t understand it,” he said. “In our way of thinking, we wanted to all go away as mates … and we found that a bit hard to wear, so … in about April or so, the blokes started to blow through and just go out to the racecourse and the showgrounds and put their names down.

“Well, the jockeys and burglars and bank managers and everybody all turned up and they were going in like it was a Grand Final. Well, some of my mates and I, we’d been together for all those years, and we’d had our fights and all our fun and games together, so we all said, ‘We’re going together,’ [and] I … joined the AIF, and became an article of King George’s army.”

He was just 19, and had to get his parents’ permission to go.

“The blokes had been grabbed in mobs of about 20 at a time, and they were holding the Bibles up and swearing to serve the King and Country and everything. Some blokes had never seen a Bible, let alone anything else… [But] they lost my paperwork … and when I went back a second day I had to go through the whole rigmarole again.”

He will never forget being sent to the jockeys’ bar to collect his gear. “It was like handing out the chocolates. They hung a pair of boots around your neck with a string, and put a hat on your head, and gave you a coat and everything else, and said, ‘Now go and sort yourselves out in the stables … to get stuff to fit.’ So blokes you’d never seen in your life before were all sitting in this jockey’s bar at Caulfield – and I’ll never forget it – they’re all sitting around the wall trying on boots and hats and swapping all this gear around.”

Bob Semple during the war: "I felt it was my duty to enlist." Photo: Courtesy Bob Semple

Semple joined the 2/2nd Medium Regiment of the Royal Australian Artillery, and was sent to Puckapunyal in country Victoria for training. He remembers arriving in the early hours of the morning, a moment which would ultimately change the course of his life.

“Fate plays some funny parts, and I’m not a fatalist or anything else, but the war teaches you an awful lot of things,” he said, quietly. “We were unloading in the middle of the night and at about 2 o’clock in the morning they said, ‘You’re going to the 2/2nd Pioneers’ … but I said, ‘No, sir, I joined the artillery.’ I was the only bloke, and … I had to stand aside... The tribes were filling all these trucks … and I found myself a lonely petunia in an onion patch … and that’s how I began in the regiment.

“They ended up in Java and became prisoners of war on the Burma Railway, and I could have been on the Burma Railway with those blokes right there that day when I said, ‘No’. I look back and I think to myself, I got off that train as they said ‘all you men into those trucks’… It’s fate, and you just accept fate, and say, well that’s it, go with the flow and do what you’re told.”

Instead, Semple arrived in Palestine in November 1940, and his regiment, which had become the 2/12th Australian Field Regiment of the 9th Australian Division because of a lack of medium guns, was sent to reinforce the besieged city of Tobruk in May 1941. They had trained by firing off a few 18-pounders in paddocks, and had been told to “imagine this is a gun” as they hooked drag ropes onto horse troughs.

“Well, I joined the imagination army then,” Semple said, laughing once more. “And from then on, we never had any guns. Britain was on its absolute knees, and we just did not have the equipment or the facilities. They lost all the heavy equipment at Dunkirk … and I did not see a gun until we lobbed into Tobruk. Did not see a gun … [but] the Germans had the finest equipment in the world. Even their water bottles were better – aluminium and light weight and all that – and their tanks cut our tanks open like a tin opener. They were using what I think were the two best guns available during the war … [and] we didn’t even have a gun to train on. Picks and shovels – we had plenty of them, digging holes and what not, and doing drills all about the place … and it nearly drove everyone mad.”

He will never forget arriving at the Libyan port of Tobruk in the early hours of the morning.

“We had to go in … under the cover of darkness or the phase of the moon,” he said. “I went in on the HMAS Vampire with spuds and ammunition and all sorts of stuff hanging onto the side of the boat … We had a water bottle, a haversack, and a few rifles, and sunken ships were all in the harbour. Then the destroyer pulled in alongside and they were saying, ‘Get off, boys. Get off, boys.’

“We were loading wounded on the other side … and we still had no guns. I thought, ‘Christ, what are we doing here? What are we doing in this place?’”

Rat of Tobruk, Bob Semple, OAM BEM, will be speaking at the Anzac Day National Ceremony at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. Read the rest of his story here.