'There isn't a day goes by that we don't think of Cameron'

Corporal Cameron Stewart Baird VC MG by Archibald Prize-winning artist Marcus Wills.

It was 22 June 2013, and Corporal Cameron Baird was leading from the front, just as he always did.

A big man with a big heart, he was a fearless warrior, a caring and compassionate soldier who was always the first off the helicopter and the last on.

He was leading his team of commandos as part of an assault on an insurgent network operating out of the Taliban-held village of Ghawchak in the remote Khod Valley of Uruzgan province, when he learnt that a team nearby had come under heavy enemy fire and needed support. Its commander – Baird’s friend – was seriously wounded, requiring urgent medical care.

Baird immediately led his team into the village to help, systematically clearing the enemy from within the maze-like village as he and his team fought to reach his friend. They were passing through a passageway when an enemy machine-gun opened fire from a heavily fortified building within one of the compounds. Facing unrelenting machine-gun fire, and with ammunition running low, Baird knew that the situation was dire and decisive action was needed.

With complete disregard for his own safety, Baird charged the doorway of the building three times, at one point having to pause to fix his jammed rifle, as he attempted to draw fire away from his fellow commandos.

On the third attempt, Baird managed to cross the threshold, allowing his team the foothold they needed to push the advantage and capture the position.

In doing so, Baird kept his team safe, but it ultimately cost him his life.

When the dust cleared, Baird’s body was found at the entrance to the room. His rifle had seized during the final encounter, leaving him defenceless.

For his actions that day, Baird was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross for Australia, the nation’s highest honour.

It was the 100th Victoria Cross to be awarded to an Australian, and the first such recognition given to an Australian commando unit.

Today, his story is told at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, where his Victoria Cross is on display in the Hall of Valour.

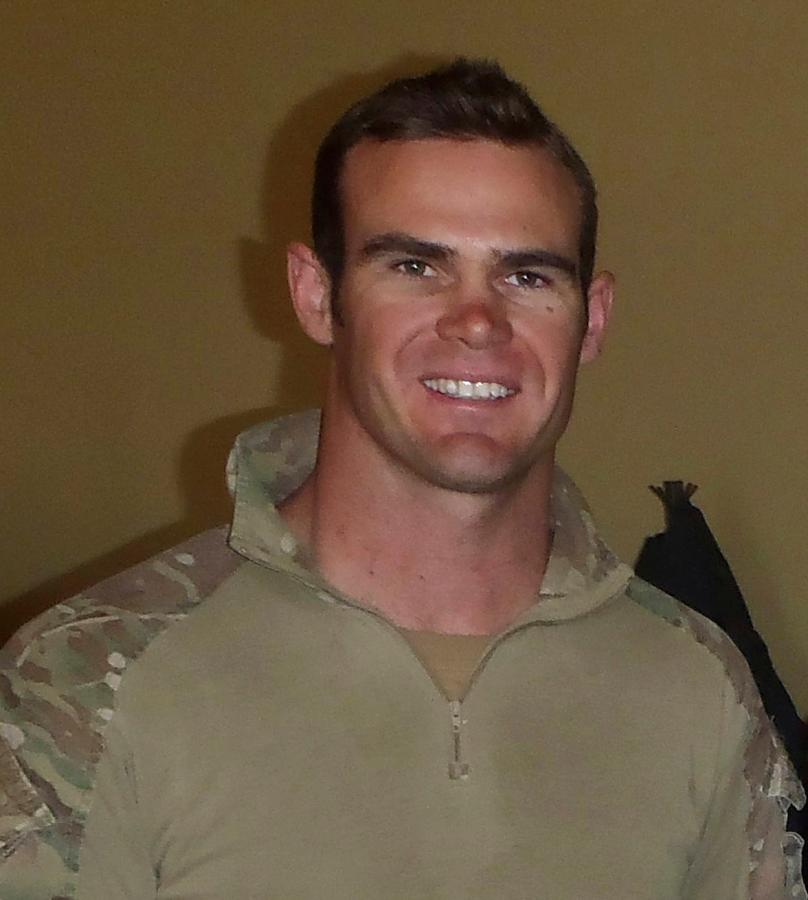

Corporal Cameron Baird VC MG. He was known as a caring and compassionate soldier. Photo: Courtesy Defence

The Memorial has since commissioned a special portrait of Baird by Archibald Prize-winning artist Marcus Wills.

The portrait shows Baird in the pre-dawn light of Afghanistan with a team of commandos as they wait for a helicopter extraction. The last to approach the landing zone, he takes a final look over his shoulder to scout for danger and protect those ahead of him.

The painting was unveiled at a special ceremony attended by Baird’s family and friends, as well as members of the 2nd Commando Regiment, and those who were with him that day.

His father, Doug Baird, said the painting would help ensure his son’s memory will live on.

“To say it means a lot is an understatement,” Doug said.

“It’s something we are extremely proud of ... and it’s in the right place.

“We know that when our time comes to pass, it will be there for the youth of Australia, or for the rest of the family, or for anybody else that wants to pop in and have a look at it, and they’ll be able to read the story, and know exactly about Corporal Cameron Baird VC MG.

“So it means the world to us.

“It’s telling his story, and preserving his history for another 100 years to come.

“And there’s no better place for it.

“We would have it in no other place.”

Corporal Cameron Baird VC MG. "He was a big man with a big heart." Photo: Courtesy Defence

Known as a highly dedicated and disciplined soldier, who always strove for excellence in everything he did, Cameron Stewart Baird was born in Burnie, Tasmania, in June 1981, the second son of Doug and Kaye Baird.

“It’s easy for a parent to say my son, my daughter, was the greatest on earth, but Cameron was as close to perfect as you could get,” Doug said.

“We never had any trouble with him growing up, and as he developed into the man and the leader that he would become, it just made us so proud to sit back and see it.

“To this day, I’ve never seen anybody walk into a room where there’s probably 50 or 60 people and they are chatting and talking and laughing and carrying on loudly and that room has just gone silent.

“He was a big man, six foot two or six foot three, and he weighed 100 kilograms, but that’s a pretty good indication of the presence that Cameron had; he was able to stop a crowd when he entered a room.”

He grew up in Melbourne with his older brother Brendan and showed a talent for sport from a young age. He had excelled at discus and shotput as child, but it was Australian Rules football that he was most passionate about.

“He was so dedicated towards his sport, particularly AFL,” Doug said.

“He was an outstanding footballer ... and he’d received letters from AFL clubs saying they were looking to draft him as a 17-year-old. But he suffered a serious [shoulder] injury and that caused a lot of problems because they didn’t know exactly how he would recover and if he’d be the same player he was before.

“He was absolutely devastated ... and he decided to go into the army.”

Corporal Cameron Baird VC MG, pictured in Afghanistan. Photo: Courtesy Defence

When he was initially turned down because of his shoulder injury, Cameron sought medical advice and had the decision overturned on appeal.

He joined the Australian Army as an 18-year-old in January 2000 and soon proved himself to be a skilled and courageous soldier.

“I remember the first conversation we had when he was able to ring from Kapooka after two or three days of being there,” Doug said. “He was saying it was the worst mistake he’d ever made in his life and he hated it.

“It wasn’t what he had expected, but then three weeks after that, when we were able to talk to him again, he reckoned the Australian Army was the greatest thing since sliced bread, and that he’d made so many mates who were going to be his lifelong friends.

“His love of Army just developed from there, and it just got greater and greater...

“He put his head down and his bum up, and he proved he was prepared to work like anybody else, if not even harder. He won their respect, and was awarded the ‘most outstanding soldier’ [at his passing out parade].”

Cameron successfully graduated to commando training at the age of 19 and was posted into the 4th Battalion (Commando), the Royal Australian Regiment, which became the 2nd Commando Regiment.

He went on to serve in East Timor and Iraq and deployed four times to Afghanistan.

Corporal Cameron Baird VC MG, pictured in Afghanistan in 2013. Photo: Courtesy Defence

On the night of 22 November 2007, the then Lance Corporal Baird was a team commander in a company ordered to search and clear a Taliban stronghold. Early in the fighting, his friend and fellow soldier Private Luke Worsley was killed by enemy machine-gun fire. Despite being under heavy machine-gun and assault-rifle fire, Baird took Worsley’s body to a position of safety and reorganised his men, neutralising the enemy machine-gun positions with grenades, and continuing the fight until the stronghold was cleared. For his “conspicuous gallantry, composure and superior leadership under fire”, Baird was awarded the Medal of Gallantry.

He was reluctant to accept the recognition, eventually agreeing to accept the award in recognition of Worsley and his mates.

He was on his fourth deployment to Afghanistan when he was killed in action while coming to the aid of his stricken mate.

“He made that decision that he would always be first off the chopper, and the first through that particular door, which is what ultimately cost him his life,” his father Doug said.

“Cameron made not only one attempt, not only two attempts, but three attempts to get through. So when you think about bravery, when you think about valour, how many people would think, ‘Well, I had an attempt, I gave it my best shot, I couldn’t do anything.’

“Who would go back a second time, let alone a third, but it had to happen because his mate had been shot and he needed to get the chopper in and get him out of the battlefield ...

Corporal Cameron Baird, VC, MG, second from right, with members of his team in Afghanistan in 2011. Photo: Courtesy Defence

“Cameron had three choices that day.

“The first was that: ‘This is too hard, I’ll call for an air strike, and we’ll pull back and just blow the whole bloody lot up.’ But he couldn’t’ do that because there were women and children there in the firing line.

“The second option was that he could have said, ‘We can’t get them out, let’s continue down to the main battle.’

“Had they have done that, the Taliban would have come out [of their stronghold], and then they would have had the enemy behind them as well as in front of them, so they most likely would have all been killed.

“The third option was: ‘I’ve just got to do it myself, I’ve just got to get in there, and do what’s got to be done,’ and so that’s what he did.

“There’s not many braver acts and it’s a very humbling thing.

“He persisted in trying to get into that hut, and on the third attempt he was killed.

“Rather than sending in one of his younger soldiers, who may have had the same fate fall upon them, he did it himself, and he gave his life for his men.

Cameron's parents Doug and Kaye Baird with his portrait at the Memorial.

“We were devastated.

“Cameron had toured so many times. When he first went to East Timor we were worried. Then when he went to Iraq, we were worried.

“We thought we’d seen the worst of it, and then Afghanistan came along, and he deployed so many times.

“We were always on tenterhooks, but we were pretty comfortable that everything would be okay.

“He’d been there a number of times, and we weren’t expecting the knock on the door that Saturday night.

“To be told he’d been killed, it was devastating. Even today, we still shed a tear, and we still have our moments.

“And I’m sure most of the other parents who have lost a son or a daughter would say the same thing: you never get over it, life’s never quite the same.

“But his love has now become our love, and that’s what we do now with Cam’s Cause.”

Cam’s Cause is a not-for-profit organisation, which was set up by Cameron’s friends in 2014 to honour and remember his life, while raising awareness about the work performed by the Australian military and the physical and psychological cost that comes with it.

Doug and his wife Kaye share their son’s story to keep his memory alive and hopefully help others.

“We’re very fortunate,” Doug said. “It doesn’t matter where we go, people seem to recognise Cameron, and they know the story, but it’s important we continue to tell it.

“It’s important, not only that we tell Cameron’s story, but that we tell the story on behalf of the other 41 soldiers killed in Afghanistan, and on behalf of anybody that’s been wounded, mentally or physically, out of that particular war.

“There isn't a day goes by that we don't think of Cameron.

“He was a big man, but he had a heart of gold. He never missed a birthday, a wedding anniversary, or something like that in the family ... no matter where he was, he would always try and make contact.

“On two occasions, we’ve had parents of soldiers who came up and thanked us for Cameron’s service and told us that their son is alive today because of what Cameron had done on the battlefield.

“And there’s at least two that we know of who have had children and named them after Cameron because of the respect they had for him as an individual, not just as a soldier, but as a leader, and the person that he was.

“We’re very proud, but we always were, regardless of the VC.

“Not only was he a good soldier, but he was a good person.

“He was the most humble person you’ve ever met in your life.”

For more information about the portrait visit here.