Their life in photos: Charlie and Olwyn Green

Charles Hercules Green and Edna Olwyn Warner were two remarkable people who came together in 1939 in Ulmarra, northern New South Wales. Born in the shadow of the First World War and having grown up in regional Australia with no higher education, their richly shared legacy has become one of the driving forces behind the commemoration and remembrance of the Korean War. Olwyn’s research and commitment to the war has catapulted it into the memories of Australians.

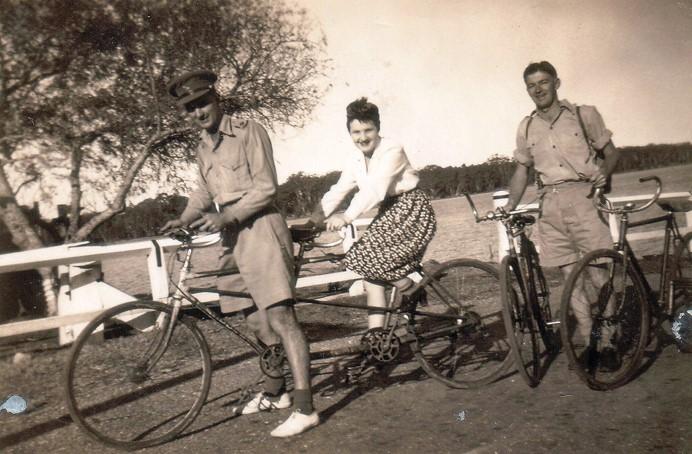

Charlie and Olwyn on a tandem bike with Ron Diamond (courtesy of the Green Family).

Charles Green was born on Boxing Day in 1919 at Swan Creek, near Grafton, the son of Hercules and Bertha Green. Known as Charlie, he worked the farm for his father and rode horses from a young age. When he was 16, he joined the local Militia unit. Two months before his 20th birthday, on 25 October 1939, he enlisted in the Australian Army in Sydney.

Charlie’s swagger stick from 41 Battalion (the Byron Regiment) while he was lieutenant in the 1930s. REL23775

Charlie had this studio portrait taken in Sydney after enlisting. He sent it to Olwyn in 1941.

He was appointed to the rank of lieutenant and assigned to the 2/2nd Battalion, part of the 6th Division. During final leave in Ulmarra in December 1939, Charlie bought a fountain pen in William Warner’s newsagency from Warner’s daughter, Olwyn, who was 16 years old. Olwyn was born on 23 September 1923 to Edna and William. Her father had served in the Royal Australian Navy during the First World War as a teenager. Charlie and Olwyn would not see each other for several years, this meeting obviously had a profound effect on them both.

The 2/2nd Battalion arrived in Egypt in February 1940, and in December moved to fight against Italian forces at Bardia, Libya.

Charlie was promoted to captain in March 1941 and shortly after, the 2/2nd Battalion moved to Greece. By April they were overrun by the German invasion from the north. Forced into a withdrawal, the battalion was surrounded, forcing small parties to find means to escape the mainland for Crete. Charlie Green’s party trekked across Greece to the Aegean Sea where they caught boats and island-hopped their way to Turkey and then Egypt.

Euboea Island, Greece, 8 May 1941. Officers and men of the 2/2nd Battalion near the village of Pili on the eve of their departure. Charlie is middle back row, wearing a cap. The man to his left is Lieutenant Colonel Frederick Chilton, the best man at his wedding in 1943. 134872

In Egypt, Charlie wrote his first letter to the girl who sold him a fountain pen almost two years earlier. Their correspondence would continue for the next two years, with Charlie writing from the Middle East and Ceylon until returning to Australia in August 1942. In September, around Olwyn’s 19th birthday, Charlie came home on leave. He took Olwyn on her first date in Grafton and she met his parents and siblings on the farm at Swan Creek. Within a week he had proposed.

Portrait of Olwyn Warner, sent to Charlie in 1941. (Courtesy of the Green Family)

Charlie was sent to New Guinea, but did not walk the Kokoda trail with his unit due to a septic foot. Just before his 23rd birthday in September 1942, he was promoted to major. He returned to Australia and was seconded to instructional duties at tactical schools in December. Olwyn and Charlie married on 30 January 1943 in Ulmarra.

Charles and Olwyn’s wedding photo. (Courtesy of the Green Family)

Charlie returned to regimental duties with his battalion in June 1943, serving in New Guinea until October, and then taking part in the Aitape-Wewak campaign in late 1944. In March the following year, he was appointed as the commanding officer of the 2/11th Battalion. The week after Olwyn’s 22nd birthday he was promoted to lieutenant colonel, becoming the youngest Australian to command an infantry battalion during the war. In 1945 he received the Distinguished Service Order for “consistently loyal and efficient service whilst commanding 2/11 Aust Inf Bn in the Wewak campaign.” On 13 September 1945, he received the surrender sword of Major Kato Morio, Commander of Kato Force, who were defeated by the 2/11th Battalion at Wewak.

With Charlie’s return to Australia after the war, the Greens spent the longest time together they would have. They returned to the Clarence River area, initially living in a house on Bacon Street in Grafton, and later moving to Alice Street. On 1 August 1947, their daughter Anthea was born.

Charlie holding Anthea on a horse in 1949. (Courtesy of the Green Family)

Charlie playing with Anthea and her dog, Sandy in 1950. (Courtesy of the Green Family).

The postwar period was challenging – their relationship had been initially conducted through letters, before their first date and wedding occurred in quick succession. However their dream of owning a plot of land, building a vegetable garden, and raising a family finally came to fruition. This came to an end when Charlie was appointed to command his old Militia battalion in 1948; in January 1949 he joined the regular army, and by the end of the year he had been accepted for the 1950 class of the Staff College in Queenscliff. The Greens had four years together before Charlie was called to command the 3rd Battalion, the Royal Australian Regiment (3RAR) in Korea.

Lieutenant Colonel Charles Green presented with a bouquet of flowers at Pusan Port after the arrival of his battalion on USS Aiken Victory, 28 September 1950. Charlie ensured flowers were sent to Olwyn every year on her birthday.

Charlie left Olwyn and Anthea to join the battalion on 8 September 1950. The night before, he told Olwyn to “look after Bubby for me”. Their relationship continued through letters, but they would not see each other again.

Charlie commanded the battalion through the initial push into North Korea, and its baptism of fire in the battle of the Apple Orchard (Yongju) on 22 October and the battle of Broken Bridge (Kujin) three days later. On 30 October, a Chinese shell hit a tree next to Charlie’s tent and the shrapnel seriously wounded him in the stomach. He was evacuated to Anju, but died on 1 November 1950.

Lieutenant Colonel Charles Green discusses a tactical situation with his intelligence officer, Lieutenant Alf Argent, in October 1950. Signaller Corporal Lindsay Beeck is behind them.

The last action picture taken of Charles Green with Brigadier Coad, half a mile east of Chongju on 29 October 1950. Brigadier Coad kept a photo of Charlie at his desk for the rest of his career.

Pair of black painted Carl Zeiss field glasses/service binoculars belonging to Charles Green.

Charles Green’s Australian Army slouch hat. The headband is marked in black ink with ‘C.H Green’.

Revered by his men, Charlie was considered to be one of Australia’s finest battlefield commanders. He had attained his rank at a young age and was a naturally decisive yet reserved leader; a 39-er who had proved his mettle in the deserts of North Africa, the mountains and islands of Greece, the jungles of New Guinea, and the cold fields of Korea.

Charlie was buried in Pakchon, North Korea on 2 November 1950, two months before his 31st birthday. He was later reburied in the United Nations Military Cemetery in Pyongyang and then Pusan during Operation Glory.

The burial of Lieutenant Colonel Charles Green on 2 November 1950 at Pakchon.

Lieutenant Colonel Charles Green’s body was re-interred at the United Nations Military Cemetery, Pusan in 1955. He was accompanied by a burial party from the 1st Battalion, the Royal Australian Regiment during Operation Glory.

The grief of losing Charlie later propelled Olwyn into decades of self-taught research into military history and the Korean War. Three months after his death, Olwyn moved to Sydney with Anthea, her mother and younger brother. The move enabled her brother to attend university and he became Professor Robert Warner. Olwyn had left school at the age of 13, but gained TAFE qualifications and a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Sydney in 1958 with assistance from Legacy. She went on to work as a field officer in child welfare, before becoming the head English teacher at TAFE for 25 years.

Olwyn receiving Charlie’s posthumous US Silver Star in 1951 (courtesy of the Green Family).

After retirement and several years in Europe, Olwyn realised she knew little about Charlie’s overseas service. At the time, she was enrolled at Hawkesbury Agricultural College (now the University of Western Sydney) completing a graduate diploma in extension writing. Her project became focused on Charlie’s career and subsequently became the biographical work, The Name’s Still Charlie, published in 1993. In 1994, she donated several boxes of her research papers to the Australian War Memorial (PR00466).

In 2002 she donated more boxes, including CDs containing the oral histories of Korean War veterans. Olwyn received the Member of the Order of Australia Medal in 2006, “For service to the community recording and documenting military history and to the welfare of veterans and their families”. In 2014 she was appointed as an Ambassador on the NSW Anzac Centenary Advisory Council. Highly respected within the Korean War veteran community her advocacy and networking among the community was captured in her revolutionary research technique of oral histories, which continue to be a valuable asset to this day.

Olwyn donated her last few boxes and items on her final visit to the Memorial in 2018.

On 23 July 2019, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Hercules Green was posthumously awarded the Order of Military Merit, Eulji, Republic of Korea’s second highest military honour. It was presented to his grandson, Mr Alexander Norman, by Prime Minister Lee Nak-yon in Seoul.

Olwyn died on 27 November 2019, aged 96, joining Charlie after almost 70 years of separation. She never remarried and leaves the legacy of her love and commitment to him as a testament for researchers to continue to learn more about the Korean War. Her daughter Anthea and grandsons, Philip and Alex intend to continue her legacy through further research into the war.

While Olwyn did not get to see the 70th anniversary commemorations of the Korean War, her research and advocacy are a large reason it has gained significance. In her book, The Name’s Still Charlie, she quoted Jack Boorer speaking of Charlie and other 2/2nd Battalion officers, “What wonderful giants of men. They looked inspiring and it gave me a tremendous sense of pride … they were giants of men in every way.” Today, these words apply just as much to Olwyn.

Olwyn after the Second World War. (Courtesy of the Green family).

With sincere thanks to the Green family.